Smooth-barked apple trees reflected in the Maranoa River, Mount Moffatt section, Carnarvon National Park. Mount Moffatt is a remote park of diverse landscapes. Broad, sandy valleys are covered with open, grassy woodlands, while sandstone cliffs to the north-east lead up to the basalt-topped ridges of the Great Dividing Range. Photograph Robert Ashdown.

The morning sun cast fingers of light between the orange trunks of smooth-barked apple trees. Strange time-carved formations of sandstone suddenly loomed above the woodland canopy. As our four-wheel-drive bumped across the sandy bed of the Maranoa River I glimpsed a distant horizon of towering sandstone cliffs and sweeping, tree-covered ranges. Like others before me I was smitten by the wild beauty of the Mount Moffatt area — part of Carnarvon National Park, in the heart of the Central Queensland Sandstone Belt. “We had a photographer out here a fair while back, a man by the name of Hurley.” Brenda Vincent, and her son Trent (at the time a senior ranger with the Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service), were leading me on a tour of this remote park. Trent and Brenda had lived and worked here when the land was a rugged highlands cattle property — long before it became one of Queensland’s most treasured national parks. Their thoughtful reflections on life here over several generations and their respect for, and knowledge of, the land through which we travelled made this a special trip. Brenda’s words had me intrigued. “The Frank Hurley?” I asked. “Yes,” said Brenda. “He was out here in the late 1940s. He took quite a few photos of the station, and we were in some of them.” As a keen photographer, I was hooked — what had the legendary photographer been doing in this remote part of Queensland?

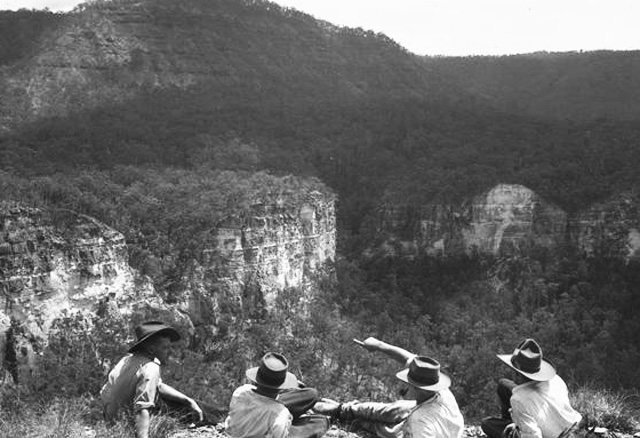

Sandstone Gorges, edge of the Consuelo Tableland, 1949. Basalt-capped ridges of Precipice Sandstone tower above shaded creeks in this remote part of central Queensland. Photograph by Frank Hurley. Nla.pic-an23148380

Frank Hurley is best known as a photographer of ice and mud — not eucalypt woodlands. Born in 1885, Hurley became an adventurer, photographer and film-maker. As a member of Sir Ernest Shackleton’s 1914 Antarctic expedition, Hurley recorded his most ‘famous’ images. Setting up his large, plate camera on the ice, Hurley photographed the ship Endurance as it was slowly destroyed by the pack–ice within which it was trapped. He then photographed the epic struggle for survival of Shackleton’s men. Returning alive from this expedition, Hurley ended up in the mud of France and Belgium during the First World War; where as official photographer with the Australian Imperial Force he recorded the carnage of trench warfare. Hurley, along with fellow photographer Hubert Wilkins, took great risks to get close to the action.

Back in town I searched the on-line digital image collection of the National Library of Australia in Canberra, and soon discovered a black and white photograph by Frank Hurley of a panel of Aboriginal rock art — attributed only to the Carnarvon Range, Queensland, between 1910 and 1962. It was almost the exact image I had taken of a panel of rock art at The Tombs site at Mount Moffatt the week before. Further searching revealed a wonderful array of Hurley’s images of the sandstone highlands, many with people in them — on horse-back, in old vehicles, leaning over the edges of those sandstone cliffs, or leading horses through the cycad-covered grasslands on the very tops of the range.

Sandstone cliffs on the edge of the Consuelo Tableland, Carnarvon National Park. Photograph by Frank Hurley. Nla.pic-an23148861

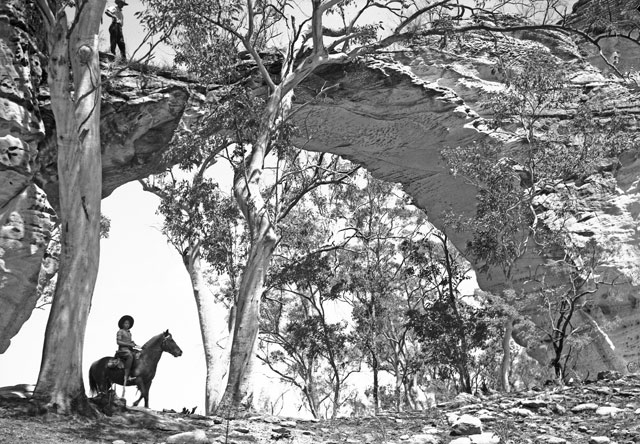

I took some of the images to Brenda at her home near Injune in the central Queensland highlands, and asked if she recognised any of the people and places. “Well,” she started, “that’s me on my pony Cupie under Marlong Arch. My sister and I and two friends had come home from school, and Hurley asked us to ride under the arch while he photographed us.” As she looked through the photographs, Brenda named people, horses and locations — many of the images having been taken on Mount Moffatt station. Some included images of her father, Jim Waldron. Eventually we were able to lodge Brenda’s notes with the National Library, replacing the scant existing data for many of the images with specific names, dates and places.

Brenda Vincent, on her pony Cupie, under Marlong Arch, Mount Moffatt Station, about 1949. Photograph by Frank Hurley.NLA.pic-an23148550.

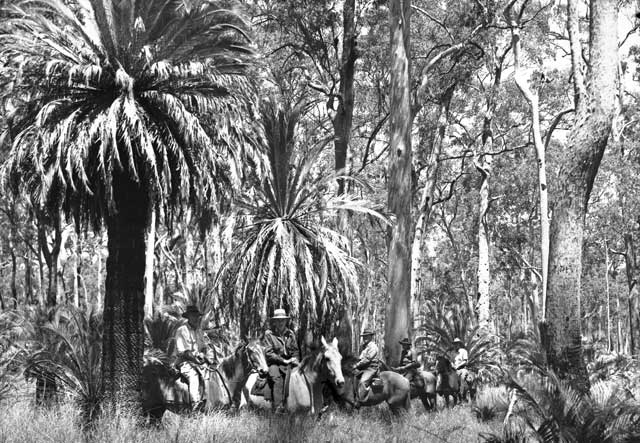

Riders on Consuelo Tableland, Mount Moffatt Station. Brenda's father Jim Waldron is at left. At more than 1000 metres above sea level, the area is often referred to as 'The Roof of Queensland'. Photograph by Frank Hurley. Nla.pic-an23148306

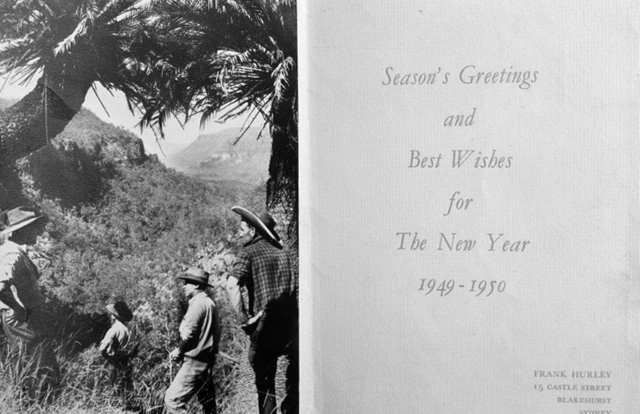

Hurley had taken these particular images in the last stage of his varied career. After the First World War, he produced films and documentaries in Australia and Papua New Guinea before returning to battlefields again in the Middle East during the Second World War. Back in Australia Hurley crossed the country, photographing the people and places he encountered. Hurley visited Mount Moffatt in October 1949 with a group that included the Director of Queensland Tourist Services and the Secretary of the Royal Automobile Club. Their trip to the top of the Consuelo Tableland, the ‘Roof of Queensland’, and back on pack horses was slow and fraught with danger. A. Donnelly, Mitchell Shire Clerk, described the trip in his report. “One packhorse slipped and fell, luckily a tree stopped him falling hundreds of feet … Captain Hurley was in great form as he focussed his camera on the amazing scenery. He was of the opinion that it could not be excelled by any other scenery in Australia”. Hurley’s images were published in several books, one of which Brenda produced. Her copy of Queensland, a Camera Study was signed by Hurley and contained a home-made Christmas card from the photographer to the Waldron family.

Frank Hurley inspired many Australian photographers and film-makers. His work on documentaries shaped the approach of later film-makers. A fearless desire to get close to the action, no matter how dangerous, put him in that league of great photographers whose images reach out to viewers long after events have passed. His photographs of the sandstone highlands are also dramatic — each image speaks of an experienced photographer working with ease within the landscape, creating strong compositions and timeless portraits. Frank Hurley died in 1962. His footprints may have faded from the sands of Mount Moffatt, but his tracks remain for generations to follow through these, and many other, wonderful photographs.

Sandstone cliffs and natural grasslands, Marlong Plains, Mount Moffatt. Photograph by Robert Ashdown.

Some day this almost inaccessible Lost World that is the Carnarvons will justify the words of Sir Thomas Mitchell — ‘A discovery worthy of the toils of pilgrimage.’ — Frank Hurley, ‘Queensland, A Camera Study’, 1950.

Rob, that's a really remarkable story – and I'm so glad that Brenda's notes have been lodged with the National Library as a result. I'm sending the link to a friend who's a curator at the NLA, I think she should know about it. Cheers.

Thanks Marion. There are so many stories out in that sandstone country. I read a thesis by Michael Morwood tat included a big section on the black/white conflict out that way and it was an eye-opener, I think very little of that seems to have been told, perhaps it is too relatively recent. I found out about Mulvaney's ground-breaking digs at The Tombs and Kenniff Cave, then got to know some members of the Bidjara and Karingbal people and was enthralled by their knowledge and stories of the area. Then there's the history of the removal of Aboriginal people, as well as their subsequent return and part in cattle station labour, staggering rock art, the Kenniffs and the many stories of station owners. It's an astonishing bit of country!

Fantastic article. One of my biggest adventures was camping there way back in 1999. I imagine it had changed little since Hurley's photographs. His work is so wonderful and important.

Thanks Russell, it is indeed a timeless sort of place, a staggeringly beautiful and mysterious area. Hope all is well with you in Japan mate, we are all still thinking of you guys.