It’s been raining now for days. Walks with my small black dog are sodden affairs, but the little hound always seems happy enough, as hounds are when out just sniffing about.

Extended rain means at least one interesting thing for those keen on natural history – fungi! And sure enough, there have been all sorts of weird and wonderful fungal fruiting bodies rising above the soil in Toowoomba’s Queens’ Park Botanic Gardens, a favourite spot for a walk for me and the dog.

So, on the theme of fungi, and with a link to Queen’s Park, here is an article by Rod Hobson on a fascinating and uncommon local fungus, the Chestnut Polypore.

An Interesting Fungus from Duggan Bushland, Toowooomba.

Rod Hobson

Anyone with an interest in the Toowoomba’s past, especially its botanical and colonial history will be familiar with the name Carl Heinrich Hartmann (1833-1887).

Hartmann was born in Dahlen in Saxony, Germany. He emigrated to Australia in 1850 and eventually settled in Toowoomba with his wife Georgina Elizabeth Anna nee Pringle around 1865. He set up his home in what is now the Alderley Street depot of the Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service (QPWS) and Hartmann Bushland Reserve. Here, he established the Range Nursery and an arboretum. Several survivors from his arboretum persist there to this day. His nursery became a major supplier of ornamental and commercial plants within Toowoomba and beyond, including plantings for Toowoomba’s fledgling Queens Park Gardens. Aside to his horticultural ventures Hartmann was an accomplished botanist and a founding member of the Royal Society of Queensland. He sent zoological specimens to the Queensland Museum and plants to Ferdinand Mueller (1825-1896) who was, for a time, the Victorian Government Botanist. Carl Hartmann travelled widely collecting botanical specimens, including two trips to New Guinea in 1885 and 1887. He died soon after returning from his second trip, from a fever contracted in New Guinea. Several species of plants and insects have been named in Hartmann’s honour. He was also a devoted theosophist.

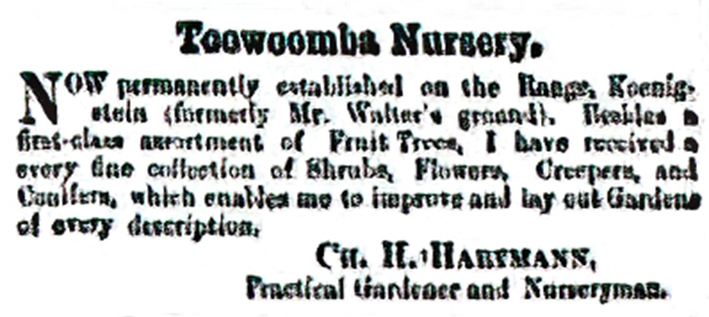

C. H. Hartmann’s advertisement for his Toowoomba nursery in the Darling Downs Gazette and General Advertiser, 16 September, 1865. (Source: Trove).

I grew up in Rowbotham Street in Toowoomba in the 1950-60s, just around the corner from “Hartmann’s” as the site of the old nursery and arboretum was known locally. It still is, though Hartman(n) is now variously spelt with one or two n’s. My family was friends of some of the Hartmann descendants who still lived in the area and I went to Rangeville State School with two of the Hartmann boys. We stole bamboo Bambusa sp. (balcooa?) from the old arboretum site when we were kids, but the species made poor fishing poles. The name Hartmann is firmly ensconced in local lore. So, anytime I hear or read the name Hartmann my interest is immediately piqued.

Rod with bamboo still growing in the Hartman’s Reserve, Toowoomba. This is quite probably Bambusa balcooa, a ‘descendant’ of the original bamboo planted by C. H. Hartmann in the 1800s. This would then be a remnant of one of the few clumping bamboos planted in Australia during the first half of the 20th century. Photo R. Ashdown

On the 28 October, 2020 I was walking the dog in Duggan Bushland in Leslie Street, which is only about five to 10 minutes’ walk from the site of Hartmann’s original residence and today’s QPWS depot. At one stage my interest was attracted to two large fungi growing at the foot of an old, fire-scarred eucalypt just off in the bush from one of the walking tracks. On a closer inspection I found them to be a species of polypore, large and irregularly shaped with a rich red-brown cap and yellowish underside. I didn’t know what to make of the fungus so took one, as a specimen. I remember that the stipe did not come free of the ground with its distal portion intact, as I expected it would. It broke with a jagged end, but I put this down to my inadvertent rough handling of the specimen. This fracture was later to provide supportive evidence in the identification of the specimen.

Chestnut Polypore Laccocephalum hartmannii, at the base of a burnt eucalypt, J. E. Duggan Park, Toowoomba, October 2020. Photo R. Ashdown

When I arrived home, I spent several hours in an attempt to identify the fungus but could not come up with a satisfactory identification so sent off some photographs to a few acquaintances whom I know to be adept at fungi identification. The answer to my conundrum arrived quickly, from Nigel Fechner through Vanessa Ryan. Nigel is the Queensland Herbarium’s mycologist, and he was very interested in my find that he identified as a species of Laccocephalum (lakkos = stone + kephalos = head; from the Ancient Greek). He also told me that specimens of this genus were poorly represented in the Queensland Herbarium’s collection and hoped that I’d retained it. As I read this email the fungus was on my desk in front of me awaiting its fate. Fortunately, Nigel’s interest prevented it from becoming compost and, as circumstance would have it, I was heading off to the Queensland Museum next day so was able to deliver him the specimen en route. Not long afterwards Nigel informed me that my find was the Chestnut Polypore Laccocephalum hartmannii.

Here, then, was that name Hartmann again. Searching the records, I could only find two previous specimen records of this species for Queensland. One was collected by L. Bolland at Salisbury, Brisbane on 17.02.1975 and is held, as a preserved specimen, in the National Herbarium of Victoria (catalogue number MEL 2301256A). The second, also a preserved specimen in the Queensland Herbarium (catalogue number BRI AQO645866), was collected by Francis Manson Bailey (1827-1915) but no data, other than it was collected in “Queensland”, are available. Bailey was appointed Colonial Botanist of Queensland in 1881, a position he held until his death. He was the author of the seminal work on Queensland botany The Queensland Flora published in six volumes between 1899 and 1902, followed by the index in 1905. He also published on Queensland’s grasses and Australian ferns.

The Chstnut Polypore Laccocephalum hartmannii. There are five recognised species of Laccocephalum in Australia. One of them, L. mylittae, was eaten by the Indigenous people of Australia — a common name for it was Native or Blackfellow’s Bread. It has been variously described as a ‘delicacy’ by some diners and ‘dull and uninteresting’ by others.

There are quite a few Chestnut Polypore records from the eastern coast south of the Queensland border including Tasmania, however, so it would appear that SEQ is likely the northern range limit for the species. There are five recognised species of Laccocephalum in Australia. They, along with Neolentinus and Pleurotus tuber-regium form a group generally referred to as stonemaker fungi. Laccocephalum is an interesting genus that grows from an underground storage-organ called a pseudosclerotium (sclerotium) although it has been recorded fruiting directly on tree trunks on rare occasions. The pseudosclerotium can weigh up to 20 kilograms in one species L. mylittae. This formation in mylittae wLaccocephalum The snapped off stipe of the Duggan Bushland specimen was due to my forcefully but unwittingly detaching the stipe from its pseudosclerotium, which helped Nigel with his initial identification. The fact that this genus is also fire-responsive, and my specimen was growing at the foot of a eucalypt recently charred by fire also supported the Laccocephalum case. The fungus is also said to respond to drought conditions and mechanical disturbance.

Chestnut Polypore Laccocephalum hartmannii, J. E. Duggan Park, Toowoomba, October 2020. Photo R. Ashdown

I was intrigued by the specific epithet of the Duggan Bushland specimen. I was unaware such a fungus existed until then. Was the holotype collected by Carl Hartmann and named in his honour? He lived only a stone’s throw from where I collected my specimen. Had the species persisted under our very noses undisturbed for nearly 150 years? For the next week I dredged the literature to see if my hunch was right. And it appears it was. The species was described by Mordecai Cubitt Cooke (1825-1914) as “Polyporus (Mesopus), Hartmannii Cke. – Type sp. No. 42968” and annotated “On ground, Toowoomba, Queensland (Hartmann, No. 10)”. This was published in Grevillea 12 (No. 61) :14 (September,1883) in Grevillea – a Quarterly Record of Cryptogamic Botany and its Literature. Cooke was an enthusiastic mycologist. He launched and edited Grevillea during the last 12 years of his working life in the botany department of London’s Kew Gardens museum. On his retirement in 1892, the publication of Grevillea fell into the hands of his successor George Edward Masse (1845-1917) and ceased publication soon after in 1893. In 1896 Cooke, Masse, Carlton Rea and Charles Bagge Plowright, along with other mycologists, co-founded the British Mycological Society. It was in a copy of Grevillea held in the Farlow Reference Library of Cryptogamic Botany, Harvard University Herbaria and Libraries that I eventually tracked down Cooke’s description of what we now know as the Chestnut Polypore Laccocephalum hartmannii. To date (December 2020) the only Chestnut Polypore specimen held in the Queensland Herbarium, aside to Bailey’s old, preserved one, is the Duggan Bushland individual from October 2020.

The genus Laccocephalum (Polyporaceae) was erected in 1895 by Daniel McAlpine and Otto Tepper. McAlpine (1849-1932) was appointed Government Vegetable Pathologist in May 1890 in the Victorian Department of Agriculture. Johann Gottlieb Tepper (1841-1923) was a Prussian-born botanist, plant collector and entomologist who spent most of his career with the South Australian Museum. According to Pat Leonard (2012) writing of the genus in the Queensland Mycological Society’s Queensland Fungal Record, “No true Laccocephalum species have yet been sequenced.” Nigel Fechner was happy to get this fresh material, which certainly appears to have been collected from the immediate area of Carl Hartmann’s original specimen, in order to carry out this genetic work. It appears that Carl Hartmann also collected Native Bread described by Cooke and Masse in 1893 as Polyporous mylittae. Hartmann collected a specimen near Toowoomba in 1884 that is held in the National Herbarium of Victoria (catalogue number MEL 1054943A). I kept an eye on the remaining Duggan Bushland fungus until the 9 November when the survivor was a desiccated and amorphous mass on the woodland floor and, tempted as I was on several occasions to exhume the pseudo-sclerotium resisted the urge. Hopefully, this Chestnut Polypore will regenerate post the next fire, a fascinating fungus.

Everyone needs a truffle-hound when out looking for fascinating fungi. Rod with Gordy, inspecting the elusive Chestnut Polypore. Photo R. Ashdown

Finally, an interesting aside to my find was the emergence from the specimen of several small, brown beetles that spent the evening disporting themselves over my desk. These proved to be a species of Pleasing Fungus Beetle of the Family Erotylidae (ref: Chris Burwell in The Queensland Mycologist, Vol. 2, Issue 3 – Spring 2007). As the family name suggests, some species can be brightly coloured and patterned but mine were mere small brown jobbies. The fungus’ cap and underside were riddled with the pinhole-sized entrances of these beetles.

And now there’s also the Ravine Orchid Sarcochilus hartmannii from the, “timbered mountain ranges behind Toowoomba …”. The thread that runs through these stories is a never-ending one. Still unravelling. Still fascinating. Carl Heinrich Hartmann – what a legacy you’ve left Toowoomba in particular and botany in general, and me.

Footnote: Any reader wishing to know more about Carl Hartmann should talk with Toowoomba Field Naturalists’ Dr. John Swarbrick who is an authority on Hartmann’s life and times.

— Rod Hobson

[This article was first published in the March 2021 edition of the The Darling Downs Naturalist, newsletter of the Toowoomba Field Naturalists Club.]

Rod Hobson is a naturalist and retired Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service ranger who lives in Toowoomba, Queensland. Rod was awarded the 2021 Queensland Natural History Award by the Queensland Naturalists’ Club, an award that is presented annually to recognise people who have made outstanding contributions to natural history in Queensland.

What a fascinating read! I hope I see a Chestnut Polypore one day. I thoroughly enjoyed learning the history surrounding this topic and also Rod’s entertaining style. And as a bonus, we were treated to an appearance by the mini-wolf and the truffle-hound. Excellent! Thank you, Rob and Rod.

Thanks for the comment, Jane, much appreciated. Who would have thought there as so much history associated with one species of fungus? I look forward to seeing some more of your great fungi expedition photos soon. Best, Rob.