Taking photos

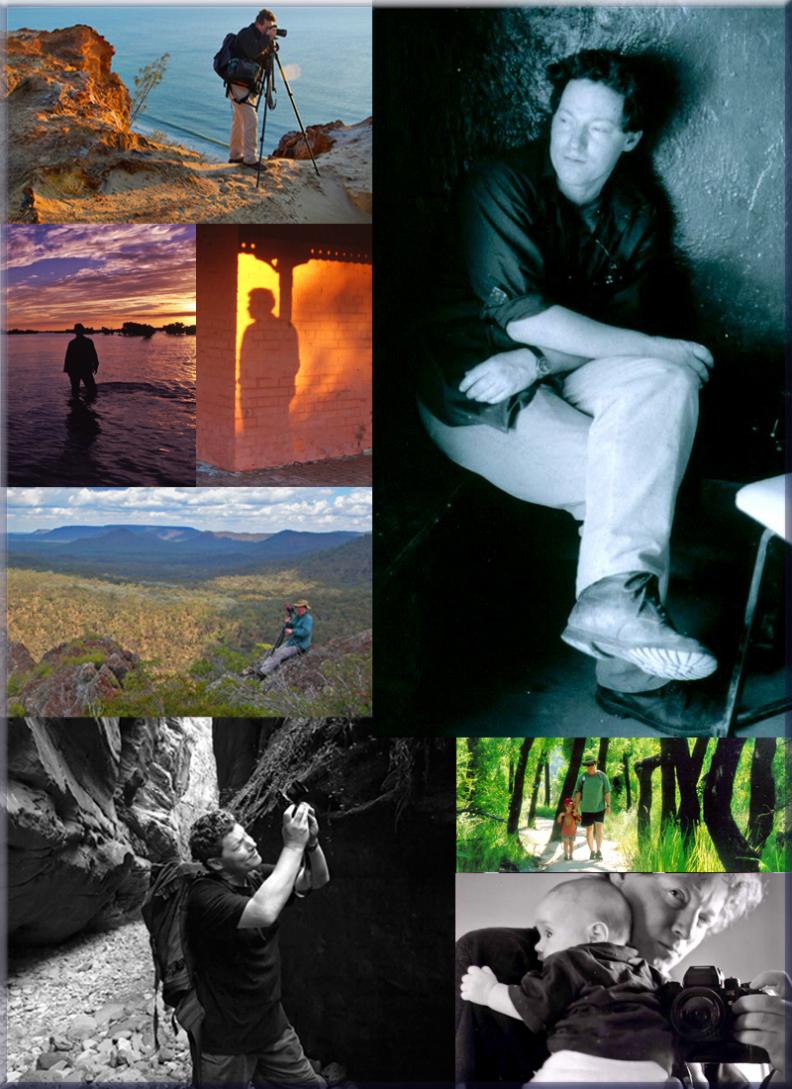

I've been messing about with cameras for way too many years. My first camera was a Yashica twin-lens reflex, given to me by my father (a rock climber, bushwalker and photographer) in the early 1970s.

This was a time when the word ‘digital’ meant something about fingers or numbers. The Yashica had a ground-glass viewfinder that you looked down into from above while rolling a large dial on the side of the camera to focus the hazy, floating, phantom reflection of the world. This was mesmerising and memorable fun. I remember the smell of the 120 roll film as the foil packet was opened and the film was wound onto the spool, and the delicate click of the leaf-shutter. I gave that camera to a friend long ago, and friend and camera have become lost forever — as people and things do.

While the gear has changed over the years, that excitement of taking photos has not. It's always been a magical process for me. My photography developed along with an interest in exploring the natural world, and a camera of some sort has always been in my backpack or hands. Time spent exploring a local patch of scrub or a distant national park always helps me cope with life back in the 'real' world. I try not to get too competitive about photography. Everyone sees the same thing differently, and photography reflects the view of the photographer. So, it's a personal journey for me, but one inspired by the work of others and one made all the better by the time spent trying to capture some elusive moment with fellow photographers.

I am not a professional photographer. I currently work as a Senior Ranger with the Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service, an organisation with a long and proud history of protecting and sharing Queensland's national parks. My role is largely technical support and desk-bound, but I get to work with some fine and dedicated people and occasionally visit some remarkable places. While our national parks were initially created for recreation and are increasingly important as places people can visit to explore and seek solace in nature, our understanding of the role of the 'protected estate' for conservation of ecosystems, and the intricate web of fauna and flora within them, has increased over the decades. Like many others, I have also come to appreciate that these places were never untrammeled wilderness areas just waiting to become tourist destinations, but are cultural landscapes long known by, and still intimately connected with, the first peoples of this land — for so many generations.

While it was once said to me that you are either a good photographer or a good naturalist, I'm happy to juggle the two as much as possible. I enjoy the discipline and fun of framing little pieces of the world in the pursuit of an exciting image. The camera is a device that can interfere with you taking in what's around you, but it can also be a wonderful tool for exploring the world and sharing what you discover with others.

The camera has helped me to slow down and take a closer look at things. Lots of hours wrestling with expensive slide film taught me about the need to take my time, still a good idea with today's digital cameras. I love capturing the character of small creatures, and I like looking for the patterns within the apparent chaos of nature. While it's my idea of paradise to be off in the swamp with a camera, I'm usually to be found at work or home. However, there's always a challenge in discovering those things that survive in and around our urban areas. If we could only see the trackways and territories of all the creatures that cover our own spaces, I think we'd be astonished. Humans think that we're the centre of everything, but we are just one part of the scene. We should be grateful every day for the web of life, the biodiversity, that surrounds us, even in the suburbs. The devil, and the delight, is in the detail.

The modern city is a zoopolis, with an overlap of human and animal geographies, where a keen-eyed and patient naturalist can find endless opportunities to stimulate the mind and feed the soul. — Lyanda Lynn Haupt.

As people drive great distances to explore wild places such as national parks, it can be easy to forget that nature lives all around us — in our backyards, bush blocks, parks and reserves, and these places, as well as the larger, remoter areas, are worthy of our consideration, respect and protection. I've grown up in the south-east corner of Queensland, a place of astonishing biodiversity, and over the years I've seen the bush reserves and corners of this wonderful part of Australia become ever diminished by development. The future value of these places for recreation and restoration is undeniable. I believe that it is important to strive for balanced development, and I respect the many conservationists working to achieve this. We need places to live, but we also need to leave places for our fellow species to live.

We need another and a wiser and perhaps a more mystical concept of animals. Remote from universal nature and living by complicated artifice, man in civilization surveys the creature through the glass of his knowledge and sees thereby a feather magnified and the whole image in distortion. We patronize them for their incompleteness, for their tragic fate for having taken form so far below ourselves. And therein do we err. For the animal shall not be measured by man. In a world older and more complete than ours, they move finished and complete, gifted with the extension of the senses we have lost or never attained, living by voices we shall never hear. They are not brethren, they are not underlings: they are other nations, caught with ourselves in the net of life and time, fellow prisoners of the splendour and travail of the earth. — Henry Beston, “The Outermost House: A Year of Life On The Great Beach of Cape Cod.”

Rob Ashdown

Toowoomba/Queensland/Australia