Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service ranger Bryan Phillips-Petersen recently took this photograph of a Tiger Snake (Notechis scutatis) on a track at Bunya Mountains National Park.

Tiger Snake, Bunya Mountains National Park. Growing to a length of two metres, this is a large, highly venomous member of the Elapid family of snakes. This species varies in colour throughout Australia, but usually they have ragged-edged pale bands (hence the common name). In Queensland they are found in some upland rainforest areas and in some coastal lowland parts of the Sunshine Coast. They feed mainly on frogs. The flattened head is a warning to stay well clear. Photo courtesy Bryan Phillips-Petersen.

It’s a beautiful reptile — a species that I’ve kept an eye out for at the Bunyas during visits over many years, with only one brief sighting that gave no chance for a photo.

Given its fierce look and common name, this is a snake that might invoke thoughts of an aggressive, attacking reptile. However, while this is a dangerously venomous snake responsible for fatalities, its reputation as a fierce animal is not deserved, according to herpetologist Steve Wilson:

The Tiger Snake has an undeserved reputation as being very aggressive, yet it is quite a timid snake that avoids confrontation. Very large individuals are often quite unconcerned by the presence of people. Even when provoked they give plenty of warning with an impressive threat display, flattening the neck and forebody and hissing loudly. Only as a last resort will the snake strike, but given its abundance around southern cities it is not surprising that this highly venomous species is second only to the Eastern Brown Snake as the most common cause of snake-bite death in Australia.*

Rising abruptly from the surrounding plains, the cool peaks of the Bunya Mountains reach more than 1,100 metres above sea level and offer spectacular mountain scenery, views and abundant wildlife. Bunya Mountains National Park (declared in 1908) is Queensland’s second oldest national park. It shelters the world’s largest stand of ancient Bunya Pines (Araucaria bidwillii).The park is home to about 120 species of birds and many species of mammals, frogs and reptiles. Several rare and threatened animals live here, including sooty owls, powerful owls, the black-breasted button quail, a skink species and a number of mammals. Photograph Robert Ashdown.

Once the most common cause of snake-bite death, Tiger Snakes have now been surpassed by Eastern Brown Snakes. It is thought that this change may be due to the difference in favourite prey items. Tiger snakes like to eat frogs, which have declined in numbers in many areas favoured by humans areas due to habitat clearing and other factors. On the other hand mice — the favourite food of brown snakes — have only increased in numbers around humans.

Tiger Snakes are less common in Queensland than in southern parts of Australia, where they are widespread in cool moist areas such as swamp edges and creek banks. In Queensland they are found in upland rainforests such as the McPherson Ranges and the Bunya Mountains. They can also be found in coastal wallum and heath areas of the Sunshine Coast. An isolated population is found in the Mount Moffatt section of Carnarvon National Park.

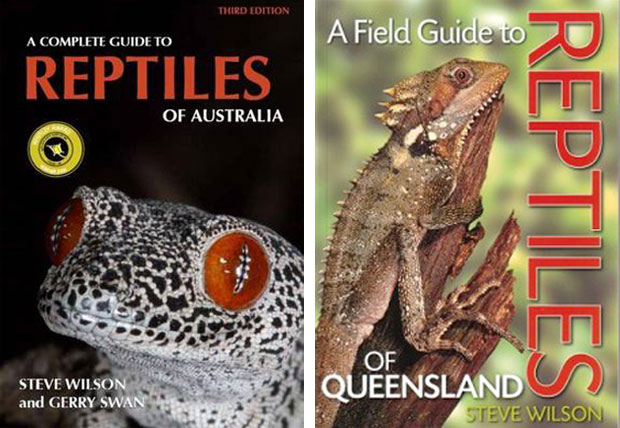

*Reference: What Snake is That? Gerry Swan and Steve Wilson, 2008.

Links: