I am crouching on the edge of a freshwater swamp somewhere in the middle of Moreton Island.

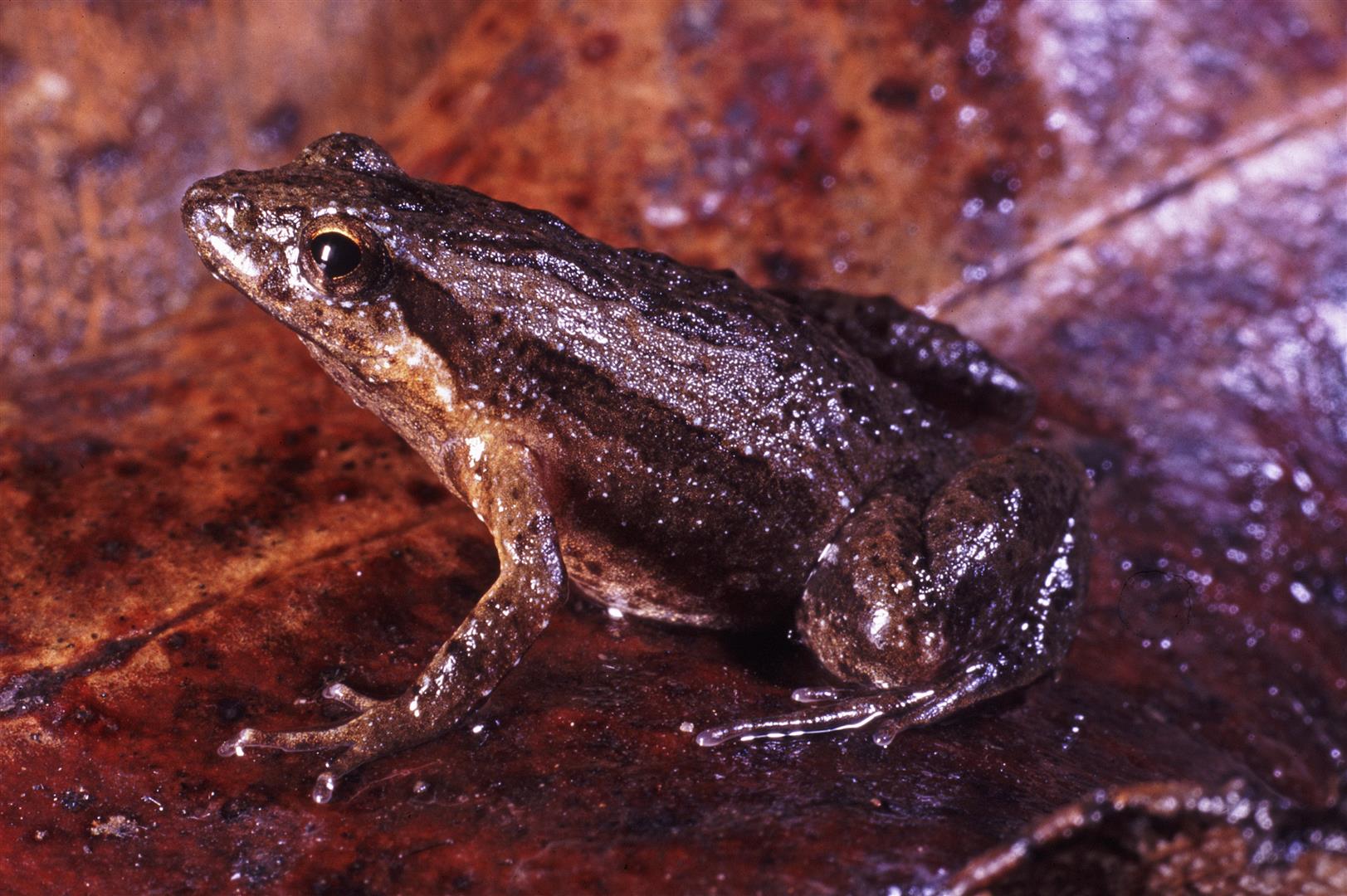

A Wallum Sedge Frog ( Litoria olongburensis ), only about 3cm long, hides in sedges of an ‘acid’ lake. Its quavering call has been described as ‘somewhat reminiscent of an accelerating motorcycle’. All photographs by R. Ashdown. Click on images for a closer look.

It’s a hot summer evening without a cloud in the sky, but I’m wearing a raincoat and sweating. Peering into a wall of grey sedges, camera in hand, I try to spot a tiny frog. The Wallum Sedge Frogs I seek are not helping me. One calls every now and then, with a sound like a distant accelerating motorcycle, but when I turn in that direction another starts up from somewhere else, confusing me completely. These tiny frogs are perfectly camouflaged and cling to sedges. They’re not the only thing hanging out on the sedges, hence the skin-covering raincoat. Nests of paper wasps abound and I’ve been stung several times on previous attempts to see a frog.

Fellow naturalist and photographer Eric Vanderduys and I had been on a long bushwalk through the centre of the island, exploring this colourful coastal habitat. It was 1998 — in the pre-digital era — where every roll of exposed film held miserable failures and exciting successes, all to be revealed only after an interminable wait for slides to be developed and returned. Like many other naturalists I struggled with primitive flash systems and expensive slide film, all the while becoming ever-more addicted to capturing images of the ‘small world’.

A photographic subject we sought on our Moreton Island walk was the ‘acid’ or ‘wallum’ frogs. The term ‘acid’ was applied to a small group of frogs in 1975 by Glen Ingram and Chris Corben (researchers, taxonomists and serious frog legends) in a paper discussing the frogs of North Stradbroke Island.

These frogs, and their tadpoles, thrive in the acidic waters of eastern Australia’s coastal wallum swamps and wet heathlands. The undisturbed swamps and lakes of Moreton and Stradbroke islands are perfect places for ‘acid’ frogs. This is a singular group of amphibians, in a land where our 230 or so species of frogs — such seemingly fragile creatures — reveal all manner of surprising adaptations to the various habitats of our dry continent.

In 1838, the (now vulnerable) Wallum Rocket Frog (Litoria freycineti) was the first frog to be described in the genus Litoria, which means ‘beach frog’ in reference to this frog’s coastal distribution. Moreton Island.

The acidic waters of a Moreton Island lake are stained brown with tannin from decomposing vegetation.

There are four frogs in the ‘acid’ group — the Wallum Sedge Frog (Litoria olongburensis), the Cooloola Sedge Frog (Litoria cooloolensis), the Wallum Froglet (Crinea tinnula) and the Wallum Rocket Frog (Litoria freycineti).

These little survivors have a lot on their plates. Their preferred habitats are threatened, being cleared or fragmented for residential development. Changes to the hydrology of the ephemeral wetlands found in these coastal ecosystems are caused by groundwater extraction and canal development. Introduced fish, such as Mosquito Fish (Gambusia sp.) feed on frog eggs and tadpoles. As if all this was not enough, the spectre of climate change and its yet-to-be-known effects looms large — a threat I’d not imagined all those years ago while stalking the Wallum Sedge Frog on Moreton Island.

Luckily, some insight is being gained into the lives of acid frogs by researchers from Griffith University, including Dr Katrin Lowe. Dr Lowe has been studying the complex relationships between climate, hydrology and water chemistry and their effects on the Wallum Sedge Frog. Studies on how these frogs respond to environmental conditions, and how they are able to time reproduction in terms of temperature and rainfall, may shed some light on how acid frogs will respond to long term changes in wetlands.

Research by Dr Lowe and her colleagues has also helped inform management of our protected estate, principally national parks, so important for the future of threatened species such as acid frogs. Fires are common in national parks, and the way fire is managed affects the fauna and flora protected within these areas.

The rare and threatened Cooloola Sedge Frog is found in coastal melaleuca woodlands, perched lakes and wallum swamps in southern Queensland. Cooloola section, Great Sandy National Park.

The Griffith University researchers believe that acid frogs are resilient and highly adaptable. They can survive fires by sheltering quickly within the wetter, cooler parts of their habitat, and can breed in fire-altered environments. However, the researchers caution that the long-term resilience of these frogs depends on how wet things are. If it’s drier and hotter they have less chance of surviving fires. Hazard reduction burns are therefore best conducted in these habitats during cooler, wetter periods, when the frogs have a better chance of survival and population recovery.

How will these frogs cope, however, with a drier and hotter climate, when more fires could put entire populations at risk? Long-term monitoring by researchers is important in understanding what is happening with such little-understood species.

The tiny (<2cm) ground-dwelling Wallum Froglet (Crinea tinnula) is variable in appearance. It is one of six species of the genus Crinea found in Queensland.

Frogs continue to capture my imagination. Armed with more sophisticated (but still temperamental) digital camera gear, I still enjoy messing about in the dark with dodgy flashes and a macro lens. Sometimes I’m talked into photographing far trickier subjects, such as people. While photographing the wedding of two ranger friends recently, the groom’s father remarked that I must enjoy photographing people. “No”, I replied, “frogs, snakes and lizards are my preferred subjects.” I think he feared for the outcome of the wedding album.

And as for my companion on that bushwalk long ago? Eric now works for CSIRO, and in 2012 published his Field Guide to the Frogs of Queensland. I think one of his photographs from our Moreton Island walk, that of a Wallum Rocket Frog, ended up within. Each of Eric’s beautiful images of Queensland’s diverse frogs has a story behind it. I understand a little of the theme that runs throughout the book’s images — that of countless hours spent struggling with head-torches, cameras and flash units in dark, difficult conditions in pursuit of a couple of photographs of ridiculously elusive subjects, complete experts at not being seen, let alone photographed. However, the memories of the search and times spent in such beautiful locations mean that any minor hardships, and wasp stings, are soon forgotten. And, what could be more rewarding than eventually sharing the results of such endeavours with others in a book, or a blog post?

Frogologists Eric Vanderduys (left) and Robert Ashdown lost on Moreton Island in search of acid frogs, 1998. (Note compass and map – GPS? What’s a GPS?).

Originally written for the Summer 2014 edition of Wildlife Queensland News.

- More about Field Guide to the Frogs of Queensland.