Mention mistletoe to Australians and the Christmas tradition of kissing under one would probably come to mind. That is, getting friendly under a northern-hemisphere plant — which they have probably never seen.

However, we have our own mistletoe, with at least 90 native species found in Australia (and probably none of them have ever overshadowed kissing couples in our December heat).

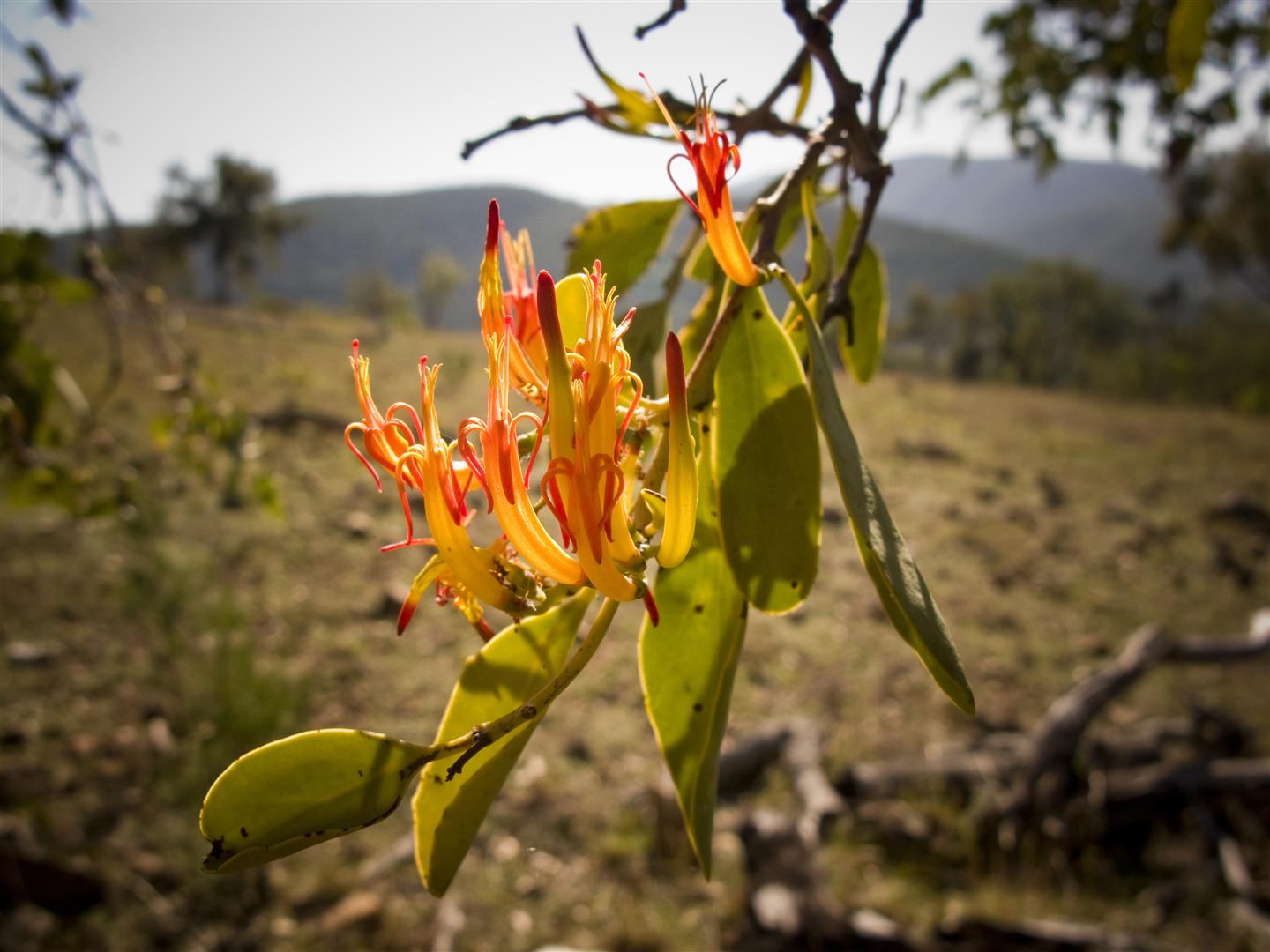

Mistletoe flowers, seen here in a eucalypt at Yelarbon State Forest, are a colourful feature of Australian woodlands. Photo R. Ashdown.

I’ve always found Australian mistletoes colourful and interesting plants, despite the reputation they seem to have as a pest and parasite. Is this reputation deserved? This blog post presents a perspective on these plants by natural historian Rod Hobson, with some notes on recent research by Dr David Watson and images by guest photographers Mike Peisley and Craig Eddie.

Under the Mistletoe — Rod Hobson

This may come as a surprise to many but contrary to popular belief mistletoes are not parasites. Botanists regard mistletoes as ‘hemi-parasites’, that is ‘half-way parasites’. Biologically, a parasite is an organism living in or on another organism (its host) from which the parasite obtains its food. Mistletoes don’t take anything from their host other than sap water and any minerals therein. They have green leaves therefore they have chlorophyll, which means that they are fully photosynthetic and process all their own food. During long droughts mistletoes suffer severely, as they don’t have any of the various means to conserve water that their hosts might possess. This is especially so if the survival strategy of the host includes restricting water flow to its outer branches. This process thus ‘starves’ the mistletoe of this essential commodity and the mistletoe may eventually succumb to this tactic.

The orange of mistletoe stands out against the green of eucalypts at Sundown National Park. Photo R. Ashdown.

Harlequin Mistletoe (Lysiana exocarpitenuis). Mistletoes not only provide food for many native animals, birds and insects but are also a source of shelter and nesting sites for many species. Several types of honeyeater including wattlebirds and friarbirds have been recorded nesting in mistletoe clumps. There is even a record of the secretive Grey Goshawk (Accipiter novaehollandiae) nesting in mistletoe. Many birds such as the mistletoebird, cuckoo-shrikes, ravens and crows, cockatoos, shrike-thrushes, woodswallows, bowerbirds, even cassowaries and emus have been observed eating mistletoe. Photo Craig Eddie.

Another popular belief is that mistletoes kill trees. This is not so, as it would take a great many mistletoes to kill a tree and many large trees can be seen doing quite well despite their heavy load of mistletoes. A large number of mistletoes on a tree could well contribute to its decline if the tree was under stress from other factors such as adverse climatic conditions, disease or heavy insect attack. The outer parts of a mistletoe-infected branch will often die though, as upon germination the mistletoe’s anchor (haustorium) enters the water-carrying section (xylem) of its host. Eventually the haustorium may totally block the xylem thereby ‘starving’ the branch’s extremities of water and causing their deaths.

Many Australian mistletoes are specific to one or a few host plants. The mistletoe Amylotheca dictyophleba (pictured), however, is found on several native rainforest and mixed forest trees. It has also been recorded on introduced trees such as weeping willow, black mulberry, pepperina, camphor laurel, London plane and Liquid amber. Photo Robert Ashdown.

The small and brightly-coloured Mistletoebird (Dicaeum hirundinaceum) is often blamed for spreading mistletoes. It is not the sole culprit however, as over 40 species of Australian birds (especially honeyeaters) are known to eat the mistletoe fruit. Other animals, including the dainty little Feathertail Glider are also very fond of mistletoe.

Mistletoe mate. The Mistletoe Bird (Dicaeum hirundinaceum), sometimes known as the Mistletoe Flowerpecker. Once I got to know the quiet call of these small but striking birds I was surprised to find them just about everywhere, from my street in the suburbs to the arid mulga-lands of western Queensland. Photo by Mike Peisley.

A Mistletoe Bird swallowing a Mistletoe fruit. Boondall Wetlands, Brisbane. The lives of these birds are inextricably linked with mistletoe. This is the only Australian member of a widespread tropical family of flowerpeckers which feed almost exclusively on the fruits of mistletoes. The seed and its glucose-rich flesh are squeezed within the bill and swallowed. Within 25 to 60 minutes of being swallowed, the seeds are defecated, and are viscid, sticking to almost any surface. Almost all seeds germinate and if they have ended up on a compatible plant , a new mistletoe plant may establish itself. Photo Mike Peisley.

A female Mistletoe Bird with fruit. The digestive systems of the Mistletoe Bird are adapted to this specialised diet their stomach has become a simple sac able to digest little else other than a few insects and the alimentary canal facilitates the quick passage of seeds. Photo Mike Peisley.

Mistletoe bird excreting seed. The germination inhibitor for mistletoe seeds is carbon dioxide within the fleshy fruit that surrounds the seed. Once this is removed the seed can germinate quickly. Photo Mike Peisley.

Germinating mistletoe seeds, Barakula State Forest. The fused cotyledons make an attachment by their tip, which eventually enter’s the host plant’s vascular system. Photo R. Ashdown.

Australian mistletoes have an ancient Gondwanaland lineage with closely related species found throughout the southern continents, as mistletoe expert Dr Gillian Scott points out in her excellent A Guide to the Mistletoes of Southeastern Australia. Dr Scott, quoting the Australian ornithologist Ken Simpson, also defends the Mistletoebird. According to Ken this bird is a relatively recent arrival in Australia, coming long after the split up of Gondwanaland and the evolution of our mistletoes. Australia has 90 species of mistletoes with about 35 of them found in south-east Queensland. Our mistletoes are contained in two families, the Loranthaceae (74 species) and the Viscaceae (14 species). The Loranthaceae has large colourful flowers and fruits whereas the Viscaceae has tiny flowers and small translucent fruits.

The Bulloak, or Slender-leafed, Mistletoe (Amyema linophyllum orientale) is one of the many types of mistletoe that are food plants for several species of Australian butterflies. This mistletoe is host to the Wood White (Delias aganippe, the Cooktown Azure (Ogyris aenone), the Amaryllis Azure (Ogyris amaryllis) and the Sydney Azure (Ogyris ianthus). Photo Craig Eddie.

There is still much to be found out about these fascinating plants and new species are still being discovered. As late as 2004 a new mistletoe was described from south-east Queensland. It was named Gillian’s mistletoe (Muellerina flexialabastra) in honour of its discoverer Dr Gillian Scott. It is only known from the Darling Downs and Moreton Districts where it is found on the Hoop Pine (Araucaria cunninghami).

Extracts from the leaves of the Grey Mistletoe (Amyema quandang) have been shown to be active against laboratory strains of the Gram positive bacteria Staphylococcus aureus (golden staph) and Enterococcus faecalis. Both these bacteria can cause life-threatening infections in humans and are problems in hospital environments. It has been reported that Indigenous people of central Queensland would bruise the leaves of this species in water and drink the water for treatment of fever. Photo Craig Eddie.

Grey Mistletoe, Darling Downs, Queensland – providing essential nectar for birds, including visiting Painted Honeyeaters. Photos R. Ashdown.

Mistletoes are not the demons that popular myth paints them. Rather, they are interesting and colourful members of Australia’s prolific floral wealth. So, please stop worrying about the roses and take time out ‘to smell the mistletoes’.

[This article was originally published in the Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service newsletter Bush Telegraph, Summer 2008.]

Orange-flowered Mistletoe (Dendropthoe glabrescens). Mistletoe fruit is high in protein, carbohydrates and lipids. The leaves are high in nitrogen, phosphorous and trace elements. Mistletoes provide food for many native birds, mammals and insects especially during droughts and seasonal scarcity. Photo Craig Eddie.

Research does seem to indicate that mistletoe has become more abundant in woodland areas. Why is this so and is it really a problem? Dr David Watson, a plant biologist from Charles Sturt University in Albury, New South Wales, has undertaken an ambitious 25-year project to learn more about the place of mistletoe in Australia’s environment.

(Extract from “Misunderstood Mistletoe’ by Abbie Thomas, ABC Science online):

Studying 42 woodland remnants near Albury in New South Wales, Dr David Watson removed mistletoe from half of these areas, while the mistletoe of the other areas was left intact. David’s plan was to find out if the presence of mistletoe can influence how many other species live in an area, in particular, bird species. David believes that mistletoe is now ten times more abundant in south-east Australia than it was before white settlement. Mistletoes particularly target trees isolated in paddocks or by the sides of roads, making them all the more obvious to us. However, David has argued that mistletoe ‘infestations’ are a symptom, not a cause of a much bigger problem. Changes in fire frequency and intensity, clearing trees and a reduction in native animals have all contributed. Mistletoe is killed by fire, and many areas are burnt far less often than before. Native animals such as possums, gliders and even koalas eat mistletoe, as do certain butterfly larvae. Once these species disappear from an area, there is nothing to keep the mistletoe in check. “But in the undisturbed bush, it’s an entirely different story,” David says. “The more mistletoes present, the greater the resources available for native animals, making the plants an important indicator of the area’s health.”

Preliminary results of his long term experiment suggest that more birds do, in fact, prefer to live where mistletoe is common. Woodland where mistletoe had been left intact had 17 per cent more total bird species, and of 44 woodland birds recorded, almost 70 per cent were more frequently seen in the intact sites than the sites without mistletoe. David says many birds prefer to nest in mistletoe because it provides shade and cover. Mistletoe nesters include the Grey Goshawk, several species of pigeon and dove, honeyeaters, wattlebirds, friarbirds and many others. Quite a number of butterfly larvae also feed on mistletoe, and some caterpillars can completely strip a mistletoe of its leaves in a matter of months, providing another natural check on mistletoe.

The larvae of the Common Jezebel Butterfly feed exclusively on Mistletoe leaves. In his book on southern Australian mistletoe species (see below), David Watson lists 23 butterfly species whose larvae depend on mistletoe as a principal food source, plus an extra four species that include mistletoe among the plants they eat. A number of species of moth also have larvae that eat mistletoe. Photo R. Ashdown.

Naturalist and photographer David Murihead informed me that various Australian native Santalum species of plants ( including bitter and sweet quandongs, desert plum and sandalwood) have often been likened to mistletoes, in that they parasitise the roots of nearby flowering plants — from grasses to shrubs and trees. The larvae of certain butterfly species are known to feed on both mistletoes and Santalacea trees and shrubs. One strikingly attractive example in David’s home state of South Australia is the Wood White butterfly, pupae of which are seen here anchored to the sturdier branchlets of Santalum acuminatum growing in the Northern Normanville dunes. Photo courtesy David Muirhead.

Scarlet Honeyeater feeding on Mistletoe flower nectar, Boondall Wetlands, Brisbane. Photo by Mike Peisley.

Brown Honeyeater in search of Mistletoe nectar. The brightly-coloured tubular corollas attract the bird, while the long stamens are ready to dab pollen on the bird’s forehead. Photo Mike Peisley.

As the biology of mistletoe becomes better understood, biologists are urging that they be managed with an eye on the underlying causes of the problem. One place that did this recently was in the Clare Valley in South Australia where local residents were concerned about mistletoe infestations in local blue gums. They made it their business to learn more about the biology of mistletoes. Although some of the bigger infestations were manually removed, natural animal predators were also encouraged back to the area by fencing off areas and planting trees.

Pale-leaf Mistletoe (Amyema maidenii), growing in Mulga (Acacia stowardii), Hood Range, far western Queensland. Photo R. Ashdown.

The same species, closer view. The varied and subtle forms and colours of Australian mistletoe make them fascinating photographic subjects. Photo R. Ashdown.

David says the best way to control mistletoe infestation is by addressing the underlying cause: such as putting up nesting boxes to encourage possums and gliders, control burning of the understorey to kill excess mistletoe, and encouraging regeneration of native plants. But he takes his argument further. Mistletoe, he says, could be a powerful tool in the management of forest plantations of species such as blue gum. At the moment, such plantations are plagued by chewing insects such as beetles, and require huge expenditure on pest control. But if every, say, 100th tree were to be seeded with a mistletoe, these would eventually grow, flower and attract insect-eating birds and possums which would also eat the problem insects, effectively turning a plant pest into a natural pest controller.

Lysiana subfalcata can grow on a number of hosts, including other mistletoe species. Photo R. Ashdown.

Native mistletoe stands out when deciduous garden trees in Toowoomba lose their leaves. Photo R. Ashdown.

Mistletoebird gallery

Images: Rob Ashdown, Bernice Sigley, Mike Peisley.

Post written July, 2014. Updated May, 2022.

Links

- Mistletoes in Australia — Australian National Herbarium. This is a fabulous on-line resource on Australian mistletoes.

- Dr David Watson’s personal blog on ecosystems. A fascinating blog on ecosystem research.

- Mistletoes of Southern Australia. David M. Watson.

- The Botanical Art of Gillian Scott. Gillian Scott was the first Australian botanical artist to win the coveted Gold Medal of the Royal Horticultural Society (U.K.) in open international competition with her display of 22 species of Australian mistletoes.

- Managing Mistletoe on your property.

- Mistletoe: The Kiss of Life for Healthy Forests (The Conversation)

- Mistletoebird.

- Mistletoes: their biology and ecology

- The Mistletoes of Subtropical Queensland. John Moss and Ross Kendall

- Unveiling the misunderstood magical mistletoes of Australia