One perceives a forest of jagged, gnarled trees protruding from the surface of the sea, roots anchored in deep, black mud, verdant crowns arching toward a blazing sun. Here is where land and sea intertwine, where the line dividing ocean and continent blurs. — Klause Rutzler and Ilka C. Feller

If there are no mangroves, then the sea will have no meaning. It is like having a tree without roots, for the mangroves are the roots of the sea. — Attributed to a fisherman from the Andaman Sea

The sun has just risen above Moreton Bay and the sky is catching fire. I’m standing in the incoming tide, in that edge zone where land meets sea. The waking suburbs are less than a kilometre away, but I can’t see or hear anyone. The rising sun doesn’t have my attention. I’m looking the opposite direction, back into a tangled mangrove forest, as the first rays of the sun hit the gnarled grey trunks. Everything in front of me has come together in a brief, quiet spectacle of light and shade, and I’m transfixed by the scene.

———

The edges of things are fascinating places to naturalists and photographers. Ecologists use the word ecotone to describe the edge zone between ecosystems. Landscape photographers revel in edges, the places where the land meets the sky, the ocean meets the shore — where lines draw the viewer into the scene.

With 125km of boundary (stretching from Caloundra to the Gold Coast), Moreton Bay has plenty of edges between land and water. These are diverse places, reflecting the bay’s beauty and contrasts — with mysterious mangrove forests, mud-flats full of life and sandy island beaches. Where the bay stops the growing city of Brisbane in its tracks, the human-built environment swallows these places in walls of concrete or canal estates.

Known as Quandamooka to Aboriginal people, Moreton Bay lies close to Brisbane, one of Australia’s largest cities.

Some of the bay’s gloriously ragged natural edges have been replaced by the geometric patterns of canal estates. It is thought that about 20 per cent of the bay’s mangroves have been lost since European settlement.

Luckily, there are places in Moreton Bay where the zone between sea and land is as it has been for millennia — blurred and hard to define. In 1799 Matthew Flinders couldn’t find the entrance to the Brisbane River because it was obscured by a wall of grey-green mangroves, plants which thrive in the shallow water and mud flats of this island-sheltered bay.

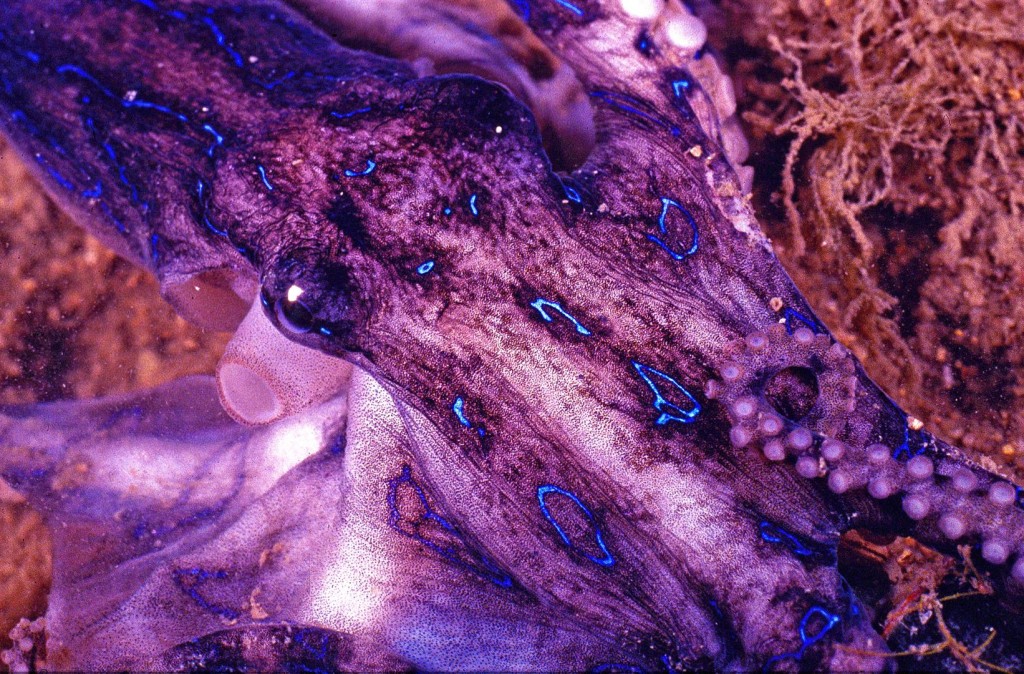

The word mangrove refers to a range of plants growing in the intertidal zone. Orange Mangrove (Bruguiera gymnorrhiza), Coochiemudlo Island.

Mangroves are, of course, important places — as home to marine life, crucial nurseries for the sea creatures our fisheries depend on, and buffer zones to storms and the power of the sea.

Important is a word that just doesn’t begin to cut it. It’s baffling then when we are reminded that some still seem to despise them, as when those who have claimed their patch of real estate by the bay see mangroves as an impediment to their view. Some even destroy them to improve their outlook, killing part of the thing they seek to enjoy, not understanding the basic truth that the bay is a vast living system, with many parts, not just some pretty vista captured within a window frame.

Australia is surrounded by approximately 11,000 km of mangrove-lined coast — around 18% of the coastline, and nearly half of this is found in Queensland. There are about 13,500 ha of mangroves on the edges of the Moreton Bay. Most are found near river mouths and in other areas protected from waves.

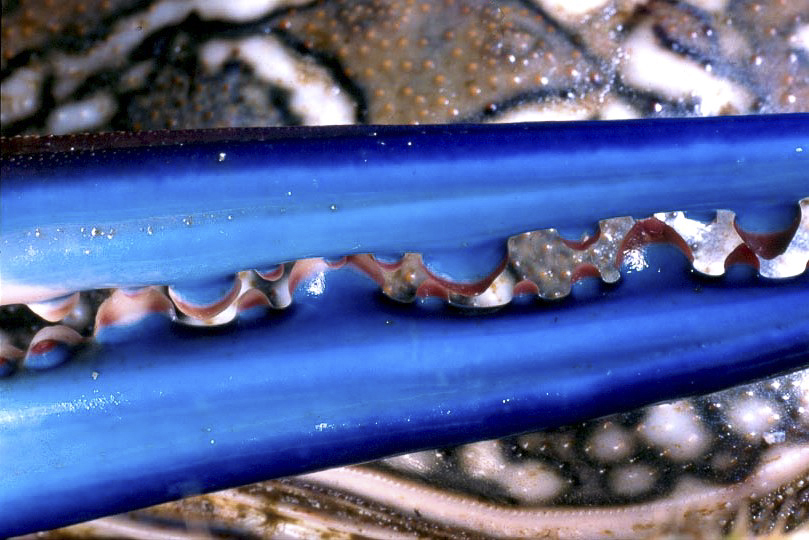

A grey mangrove seedling. Nearly 70 per cent of the prawns, crabs and fish we eat depend on the mangrove habitat for at least part of their lifecycle.

Many probably still see mangrove forests as smelly, horrible places crawling with mozzies, snakes, spiders and crocodiles. Explore one though, and light and time slip away. As the sounds of the land fade, other noises are heard — clicks, splashes, the clear piping of a mangrove kingfisher or the sweet, falling leaf call of a mangrove gerygone. There’s a gradual realisation that these muddy, shadowed places are full of life.

So where does the sea actually start or end in a mangrove zone? There’s no set spot of course, this is the intertidal zone, where the water ebbs and flows with the endless tides.

At low tide, old mangroves look like stranded, strange creatures, patterned by lichens and ringed by water-marks. They are partially consumed each day as the incoming tide pushes past them toward the land beyond. In king tides and storms the sea reaches beyond them to saltmarshes and samphire flats, sometimes even popping up in the drains and streets of bayside suburbs like some kind of unwelcome intruder.

On this morning I have waded out before dawn into the mangroves, carrying a camera and binoculars. I’m close to the suburbs but may as well be lost somewhere on Australia’s vast northern coastline, sent back in time to when there were no cities chewing up the bush beyond.

I’ve gone as far as I can, having pushed out beyond the edge of the mangroves.

As the sun rises and the first orange light hits the wall of mangroves, the wind drops and calm descends on the scene, allowing glowing reflections a brief window of life. Realising that this will only last a minute or two, I steady my camera on a shaky, mud-stuck tripod and capture one long exposure. Then, the wind rises, the moment vanishes, and a restless movement fills the mangrove forest as a new day takes over.

Weeks later I get the developed slides back and realise that this single sunrise mangrove image (the first image on this blog post) will be a favourite photograph of mine, one that will have the power to transport me from the stress of busy life to the quiet wildness of the mangroves, still there I hope, greeting each day amid the endless rhythm of the tides, home to myriad creatures, important — and just being its mysterious, magical self.