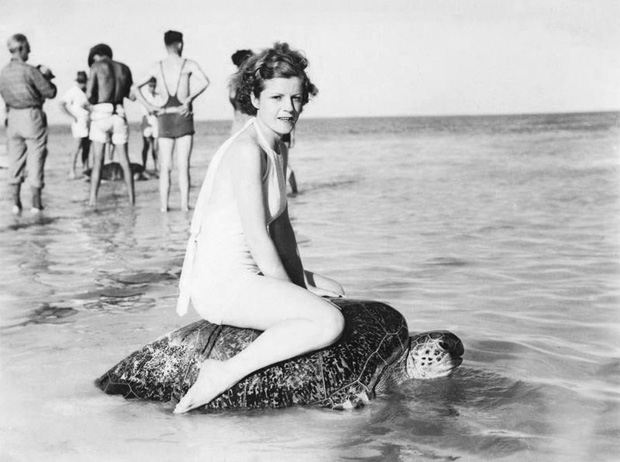

Woman sits on a turtle at Mon Repos (?) Beach. Ca 1930. Photo State Library of Queensland. Photo ID: API-100-0001-002Much has changed since this scene was captured in the 1930s. Marine turtles have faced serious problems and experienced great declines in numbers in the last seven decades. However, awareness of the plight of turtles has increased, and conservation efforts have brought successes in both understanding of turtle biology and in ways to halt their decline. Mon Repos Conservation Park, near Bundaberg on the Queensland Coast, supports the largest concentration of nesting sea turtles on the east Australian mainland. Nesting turtles at Mon Repos include the loggerhead, flatback, and green. At the peak of a prime nesting season, 20 or more turtles a night (mostly loggerheads) come ashore to nest on this 1.5km long sandy beach.

This small beach at Mon Repos, near Bundaberg, supports the largest concentration of nesting sea turtles on the east Australian mainland.

A female Loggerhead Turtle hauls herself ashore late one stormy afternoon in December 2010. Photo R. Ashdown (QPWS).

One of Australia’s most dedicated and successful conservation efforts has been based at Mon Repos. Decades of committed research by a small band of staff and volunteers has lead to a remarkable synthesis of research and public education. Access to the nesting beach at Mon Repos is controlled so that the turtles aren’t disturbed. However, people can still witness these ancient marine reptiles leaving the sea to nest as part of controlled groups led by experienced staff and volunteers from the Mon Repos Information Centre, run by the Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service (QPWS).

A QPWS ranger talks about marine turtles while people wait for their group to be called to the beach to see a turtle. Photo R. Ashdown (QPWS).

A group of turtle watchers, guided by a QPWS ranger, experiences an ancient ritual. The turtle is not disturbed by lights once she starts laying eggs in the nest she has dug in the sand. Photo R. Ashdown (QPWS).

The Loggerhead Turtle returns to the sea, watched by enthralled late-night observers. A sea turtle can be aged 30–50 before it begins to breed, and the breeding season might be once in only two to eight years. The hatchlings have a low chance of survival, with only one in 1000 possible reaching maturity. Sea turtles are very vulnerable to human disturbance, so while allowing the public to witness this event, the turtle’s well-being is of paramount importance. Photo R. Ashdown (QPWS).

A special turtle is checked by researchers at 3am. Premiere (K33061) was originally tagged as a hatchling at this beach in 1975. She is the first of the tagged Loggerhead hatchlings to be recorded returning to this beach as a breeding adult, and was recorded laying eggs on four occasions during November 2003 to January 2004. I was lucky enough to meet her here in December 2010. Photo R. Ashdown (QPWS).

Premiere heads back to sea as the eastern sky lightens. Slow and ungainly on land, it was not hard to sense her urgency in returning to the relative safety of the ocean. The more I meet reptiles, the more I like them — we share the planet with some mysterious and beautiful creatures. Photo R. Ashdown (QPWS).

Once the water broke over her, she regained her graceful power and quickly vanished — once more a thing of the vast ocean. Photo R. Ashdown (QPWS).

Dawn soon breaks, revealing the ephemeral tracks of ancient marine reptiles. Photo R. Ashdown (QPWS).

Links

- Information on Mon Repos Conservation Park and how to go turtle watching.

- Species information and status — Loggerhead Turtles.

- Migrating sea turtles have magnetic sense for longitude.

- How do marine turtles return to the same beach to lay eggs?

- Satellite tracking of Atlantic loggerheads.

- Turtle-riding on the Great Barrier Reef (thanks to Marion for this link)

- Woman riding turtle on Heron Island, photograph by Frank Hurley.