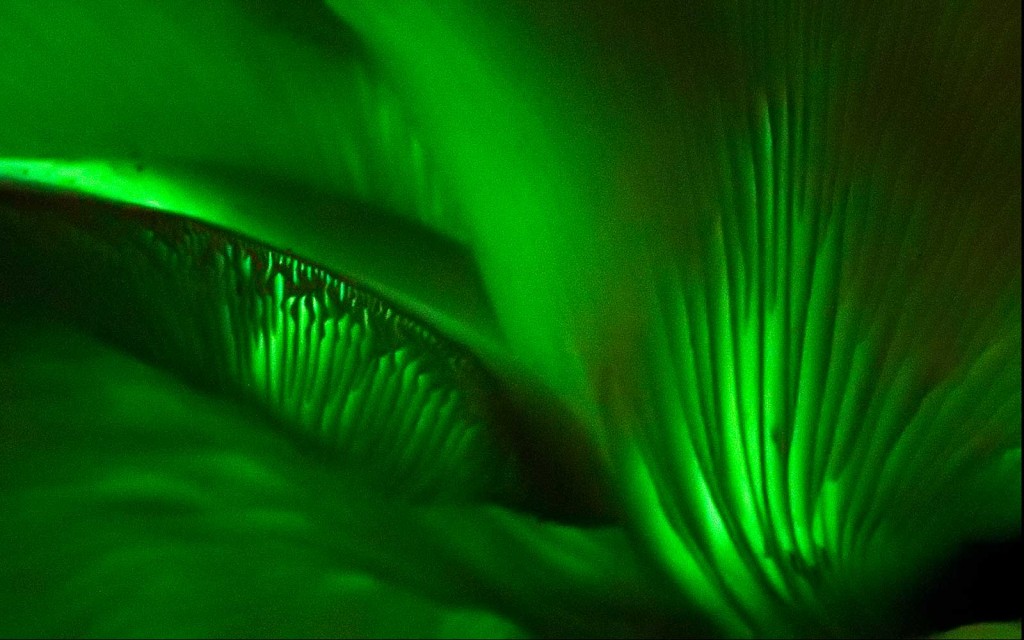

Back in June 2010 I posted an article on naturalist Rod Hobson’s discovery of the fascinating glow-in-the-dark Ghost Fungus (Omphalotus nidiformis) on the edges the Toowoomba escarpment in eucalypt woodland.

Fungi are always fascinating, but the Ghost Fungus really stands out — especially at night. A chemical reaction between fungal enzymes and oxygen causes a ghostly, and quite powerful, luminescence.

Ghost fungus, December 2010

In December of 2010 I was walking with my 10-year old son in some urban bushland not far from home, when he drew my attention to a large patch of fungus on a tree stump, saying they looked like the Ghost Fungus. I was pretty sceptical, but we returned that night and sure enough, a mysterious ghow could be seen from a fair way down the track as we approached. Spectacular and enchanting stuff.

I did not photograph them then, and when I returned in early January, there was no sign of them on the stump at all. As Rod reminded me, what we see as a fungus is only the fruiting body of the organism, with the main part invisible within the bark of stump or in the ground. Still disappointing though. Show yourself, fungus!

Same Ghost Fungus, January 2011. Or not. Hiding maybe.

After outrageous amounts of rain, and even floods through the rest of this year (flood, what flood?), the fungi magically reappeared, bigger than ever, so last night I set out with Harry in the howling wind and rain to see if we could sneak up and capture some images of the elusive things glowing away happily.

Yes, you guessed it, same Ghost Fungus, April 2011.

Yes, they were indeed glowing, but capturing them was not easy, despite their sedentary nature. Howling gales looked set to bring trees down, and rain pelted us. For some bizarre reason scrub ticks were out in this weather and Harry ended up taking one home with him, firmly attached (the trials of the assistant).

After answering the lad’s reasonable question about how I would work out an accurate night exposure of barely-visible fungi in near cyclonic conditions (“Textbook mate — mess about with tripod, attempt to focus, set on manual, guess an f-stop, open shutter, count to a hundred, then count to a hundred again, close shutter, peer at screen, curse and mumble, repeat process with different variables etc etc.”) we took a few photos, with the hapless kid holding an umbrella over me, the camera and the fungus. It got wearying, with little result, and constant water all over the lens. “Just one more,” I said, and we sat and counted erratically to two hundred again. “It’s completely bloody black!” I moaned, looking at the resulting image on the screen. “Dad,” came a weary and mildly astonished voice, “you’ve still got the lens cap on!” Hmmm.

Groan, one more try. Lens cap OFF, fumble for cable release, shutter open. Start counting.

Success at last. The Ghostly Ghost Fungus on a stormy, haunted night. Exposure details — removed lens cap, set aperture to f something (forget), count to maybe 200. Photo by HARRY and Robert Ashdown.

Ghost Fungus, again. Spooky. Photo Robert and Harry Ashdown.

Eventually we got two shots that worked, and back home we both agreed it was worth the uncomfortable excursion. What a mysterious, magical, and even ghostly thing fungi are!

Other glowing stuff:

Some Australian fungi facts:

- There are approximately 250,000 species of fungi in Australia, of which possibly only 10% have been scientifically described and named. There are at least 71 known species of luminescent fungi in the world, with six of those found in Australia.

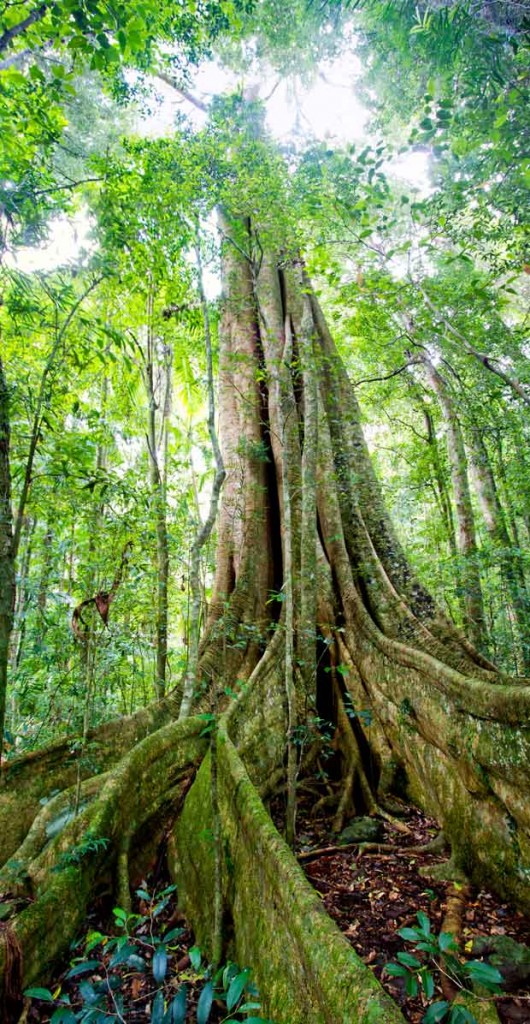

- Healthy ecosystems need healthy, diverse populations of fungi. About 95% of terrestrial plants depend on specific fungi (mycorrhiza).

- Many fungi are an important food source fo Australian animals, with at least 38 species of mammals known to eat the fruiting bodies of fungi. Some species, such as bettongs and pottoroos, eat little else.

- Fungi reproduce by releasing clouds of powder-like spores from their fruiting bodies. A field mushroom can release 200 million spores in a single hour. Puffballs can produce 15 trillion spores from each fruiting body.

- Some fungi are pathogenic, causing disease and the death of various species. However, in nature, this helps to makwe room in ecosystems which new species can fill.

- Many fungi are decomposers, releaseing nutrients by breaking down dead plants and animals — a vital part of forest ntrient cycles.

- A fungus is usually largely out of sight, with only the fruiting bosy exposed to view. The remainder, thin threads called mycelium, is underground or webbed throiugh soft, rotting, wood.

Australian fungi websites: