I’ve been visiting Carnarvon Gorge (part of Carnarvon National Park), on work trips as part of my role with the Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service, for about 15 years. In all that time I’ve never just sat by Carnarvon Creek and taken a determined look for one of the park’s most iconic creatures — platypus.

I’ve seen them briefly while walking creek-side at Carnarvon, but it’s never been much more than a glimpse. My childhood memories of platypus are mixed. As a young lad, standing fairly close to David Fleay during one of his platypus shows at his West Burleigh reserve, I marvelled at the mysterious creature that moved into view in the concrete display tank. Unfortunately, the memory is scarred by the recollection of either my brother or I accidentally kicking an empty coke bottle across the floor, not long after Mr Fleay reminded all of the utmost need for quiet and even no finger pointing. The scornful glance of the legendary naturalist was memorable.

So, on another recent quick work trip to Carnarvon, I headed down to the creek about 4.30am to see if these things really existed. If lucky, I’d get to see one, and maybe I could capture a photograph or two of the mysterious beasties. I had no hope for anything too successful photo-wise, as I’d no intention of using a flash on such shy creatures and platypus are well known for not being photogenic in the wild (like any sensible animal).

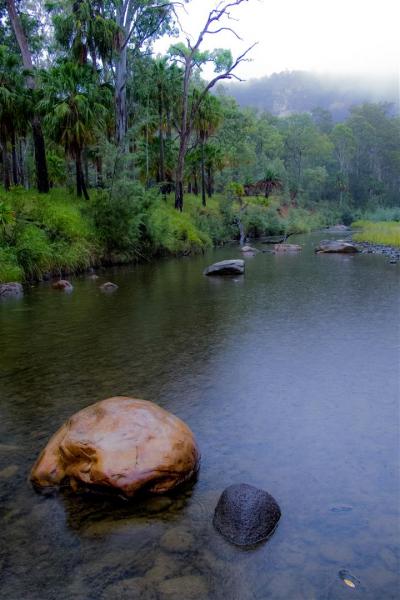

First crossing at Carnarvon Creek. A calm place at 4.30am. Click on images for a closer look. All photos R. Ashdown unless otherwise credited.

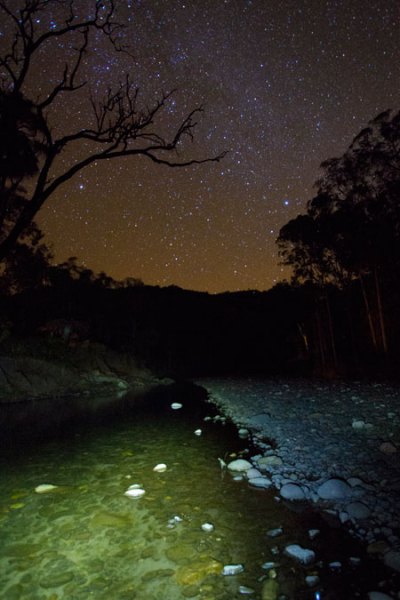

I took up a spot above the bank and sat quietly in the grass, scanning the slowly brightening waters of this marvellous creek.

Carnarvon Creek is a magical place. The water always flows, part of a process that has endlessly and relentlessly carved through basalt and sandstone to create one of Australia’s most wondrous gorges.

Multi-hued and sun-dappled creekside vegetation, as well as towering sandstone cliffs and woodland perched high above the gorge floor, are reflected in the creek’s waters. The icing on the cake is the array of animals, of which surely the platypus is the most elusive and mysterious, that call this creek home.

A quiet stretch of water. The perfect place to seek a platypus.

After a short time just sitting, a movement caught my eye. A wake was spreading out behind a moving brown lump. It was a platypus, motoring across the surface of the creek. I held my breath and tried not to kick any coke bottles.

Over the next hour, and again the next morning with a colleague (Raelene Neilson, some of whose photos are included below), I followed the progress of two platypus as they worked their way around a large, still part of the creek, not far from the visitor area.

A platypus morning seems to be spent drifting and motoring about like a tiny barge, interspersed with frequent diving and searching in the sediment for yabbies and other food. A trail of bubbles tells of a platypus searching for food on the bottom of the creek.

A swirl of bubbles indicates a platypus is grubbing about in the sediment below seeking breakfast.

Platypus are found along the east coast of Australia as far north as Cairns, down to the bottom of Tasmania and as far west as Adelaide. They are one of two monotremes (egg-laying mammals) found in Australia, the other being the Short-beaked Echidna.

Platypus live for up to 12 years in the wild and approximately 20 years in captivity because there are no predators or seasonal changes. Their tunnels, in the bank of the creek, can be from 15 to 30 metres long, and there is usually more than one entrance just above the water line. The burrows are a tight fit so that water is squeezed off their fur when a platypus enters the tunnel. Platypus have a high amount of haemoglobin in their blood, which allows them to make better use of available oxygen, so they can survive high levels of CO2 in their tunnels.

Platypus are venomous. The males have a poisonous spur on each hind ankle, which is capable of causing severe pain in humans. The female’s spurs fall off at the juvenile stage. Platypus at Carnarvon Gorge apparently only grow to around 30 cm long, possibly due to the small size of the creek, and the number of platypus living in it.

A platypus diet consists of shrimps, larvae and some insects. They find food by rummaging through the creek bed with their bill. Platypus usually feed for 10 to l7 hours a day, depending on how much food is about.

During winter and early spring females start consuming larger quantities of food and use the tail as a fat storage area to be used in the breeding season, as the female fasts for about a week after the eggs are laid.

Platypus usually mate from July to September. After conception there is a gestation period of four weeks and then three eggs are laid. The eggs are oval, light brown in colour and smaller than a twenty-cent piece. They are soft and laid in a sticky substance which allows the eggs to stick to the mother’s underside for incubation. The mother stays in the burrow, which is lined with leaves and grass, for approximately seven days and after this period only goes out to defecate. During the whole process the female has the tunnel blocked off, keeping predators out and humidity high. Each time the platypus exits the nesting burrow she takes down the wall and rebuilds it. Photo by Raelene Neilson.

The young are incubated for 10 days and once the eggs hatch they are drawn to a milk secretion area between the mothers front and hind leg enabling the young to ingest milk. The young are fed for three to four months at which time they begin to emerge from the burrow. Photograph by Raelene Neilson.

Messing about in the water … or something. Photo by Raelene Neilson.

Checking out the humans — total weirdos. Photo by Raelene Neilson.

Platypus tend to share areas and tunnels. The adult males are fairly territorial and only meet to fight over females during mating season, but females and juveniles will feed through a range of territories and generally rest in the burrow that’s closest. Colonies of platypuses keep at a fairly set level, and if conditions are not able to support the juveniles, they are forced to move on.

Carnarvon Creek reflections (click on image for closer look)

It’s a serene body of water — usually. However, as the rangers working here know, this quietly flowing creek has a wild side. Every now and then, floodwaters rage down the gorge system in an immense, turbulent show of power, tearing out creek-side trees and rolling huge boulders.

A flooded Carnarvon Creek, January 1976. Photo by Bill Morley, QPWS.

A worn and battered creek boulder bears evidence of the power of a 2012 flood.

Ranger Erin Witten is dwarfed by piled up debris from another flood, 2007. Photo QPWS.

How do platypus survive such times?

Surely some of them are killed. Perhaps they are able to wait things out in their burrows, but it’s hard to imagine how they’d do this when the floodwaters can last for days. Or perhaps they sense the approaching floodwaters and quietly head away from the creek, returning when water levels subside.

We have very few photographs of Carnarvon platypus on our QPWS files. One of them bears the caption “After the floods, the platypus come out”. I’d assume that this platypus has been photographed in the calmer creek waters not long after a flood.

Tom Grant, in The Platypus, a Unique Mammal recounts that in the first five years of a 20-year study of platypus in the upper Shoalhaven River in New South Wales, seven floods occurred, all of which changed the river from its normal series of deep pools with connecting rapids into a raging mass of brown water with no distinction between pool and rapid. Their study found that while some platypus are killed, most were not even displaced from their home ranges by the floods.

As platypus have occupied the rivers of Australia for at least 50,000 years, they have presumably evolved strategies to cope with flooding, However, it is still unknown how they ride out floods. Early naturalists suggested that they occupy rabbit burrows and hollow logs away from the river, returning later. Some recent radio-tracking work has shown that platypus of the Goulburn River avoid high flows associated with the release of water from the Eildon Weir for irrigation used a backwater area to avoid the faster-flowing water. They even found that the animals would still enter the river to feed, paddling against the current. However, it would be hard to imagine them being able to feed easily during the raging Carnarvon Creek floods, at least during the wilder periods of flooding.

The Australian Platypus Conservancy reports how damage to creek banks and burrows happens with floods:

In theory, depending on their magnitude and duration, floods could have either a positive or negative impact on platypus populations. The effect of minor flooding is likely to be relatively benign and could even improve the quality of platypus habitat, for example by flushing accumulated silt from pools.

By comparison, severe flooding is much more likely to affect platypus populations adversely. The animals may drown, contract pneumonia after inhaling water, or be swept downstream and have to find their way back through unfamiliar terrain. Their burrows may also be inundated for a substantial period of time and food supplies badly depleted due to invertebrates being washed away.

Flooding can also degrade the quality of platypus habitat if it causes banks to erode, pools to become filled with sediment, or in-stream woody habitat (logs and branches) to be deposited on land as flood waters recede.

A study conducted by the Australian Platypus Conservancy in mid-2008 examined how platypus populations in four Gippsland rivers were faring approximately 9–11 months after substantial floods occurred. In each case, flooding peaked at an estimated flow rate of more than 10,000 megalitres/day. In brief, the severity of flood-related habitat damage was inversely related to platypus population density and reproductive success: the river suffering the greatest damage had the lowest numbers of platypus and the smallest proportion of juveniles (none), whereas the least damaged area had the highest density of platypus and the largest proportion of juveniles. It was concluded that flood-related impacts can have a measurable adverse effect on platypus populations, particularly when (as was true in this study) the vegetation on adjoining slopes has recently been damaged by wildfire.

The fact that juvenile platypus are weaker and less accomplished swimmers than older animals suggests that they may be more likely to be killed by floods, particularly if these occur around the time that juveniles first emerge from the nesting burrow in summer. This is supported by the results of live-trapping surveys carried out in the Melbourne area after more than 120 millimetres of rain fell on the city in less than 24 hours in early February 2005 (the highest one-day total since weather records were first kept in 1855). The mean juvenile capture rate from February to June 2005 was less than 10% of the corresponding mean capture rate from 2001-2004. In contrast, the capture rate for adults and subadults occupying the same five water bodies from February to June 2005 was actually slightly higher than the corresponding mean capture rate from 2001–2004.

In his book Paradoxical Platypus — Hobnobbing with Duckbills, David Fleay describes the effects of floods on young platypus in south-eastern Queensland:

As a spin-off from my appointment as weekly Nature Columnist (1952-80) to the Brisbane Courier Mail, I was in touch with most platypus happenings in south-eastern Queensland. This proved not only invaluable but very instructive.

So in way or another, numerous duckbills passed through our hands, particularly those babes rescued from peril at the generally early south-eastern Queensland nest-leaving period (late December to early February).

At least four such inexperienced juveniles were actually flotsam in the mile–distant Pacific Ocean at the tail-end of cyclones. Naturally, sudden savage flooding takes victims by surprise and bears the unwary, willy-nilly into the sea.

Times of flood must bring turmoil to the quiet morning ritual that I was fortunate to observe at Carnarvon Creek.

While there is some evidence that platypus may be adapted to survive a natural event like a flood, the effects of humans on our waterways is far more detrimental to these mammals. Having survived hunting for pelts in the 19th century, platypus now face a far greater human threat — our impact on waterways due to agriculture, forestry, dam construction, mining and industrial activities. Illegal and inappropriate fishing practices, particularly the use of nets in creeks, also kill platypus. The health of platypus populations is inextricably linked to the health of our waterways, and our activities around these river systems. How we treat our creeks and rivers will determine how well platypus survive into the future.

I greatly enjoyed my brief time watching these unusual mammals. They were full of energy and life as they worked the creek in search of food, sometimes stopping to drift and seemingly take in what was going on around them.

The sense of privilege and wonder I felt while sitting next to that serene creek lingered. Back at my work desk, I paused from the cubicle chaos to think of the morning calm of Carnarvon Creek and its marvellous residents. I really hope they’ll be messing about there forever.

Carnarvon Creek. An ever-flowing wonder in the heart of arid central Queensland. A joy for human visitors, a home for one of Australia’s most mysterious creatures.

Platypus below. Carnarvon Creek twists its way beneath the towering sandstone cliffs of Carnarvon Gorge for many kilometres. An ancient landscape full of surprises. Photo QPWS.

Links: