The sounds of nature are always there, even in the city and suburbs, if you stop to hear.

Sometimes they are memorable, melodic noises. I remember lying in bed as a child in Brisbane in the dead of night listening to the cheerful call of a Willy Wagtail or the haunting, ‘mo-poke’ call of the Southern Boobook Owl. At other times the sounds are mysterious drones, clicks or whistles, all just part of the background of summer in the suburbs. Unless it’s a click that you’ve been trying to find the owner of for years.

In our street on dusk after the first hot summer day, an all-enveloping, loud, continuous guttural rumbling fills the air. This is the call of the large, green Bladder Cicada (Cystosoma saundersii). These beautiful, large green insects are hard to find, given how loud and large they are.

Catching cicadas is a childhood pastime during an Australian summer. Some species sit warily high up on tall gum trees, taking flight at the slightest movement. Others, such as this Bladder Cicada, call on twilight and are well camouflaged. If detected, these cicadas will suddenly drop to the ground, hoping to avoid being caught.

Bladder Cicadas are found in closed forest and gardens on coastal Queensland and New South Wales. In males, the large, hollow abdomen acts as a resonant sound radiator, allowing the cicada’s song to carry long distances. In our suburb, the call of these insects on a summer evening can be deafening.

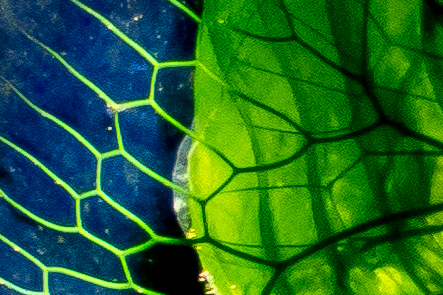

Most of the life of this cicada, like most species of this insect, is spent below ground as a nymph, feeding on the sap from the roots of trees. On warm summer nights, nymphs leave the safe, dark earth, climb a tree or fence post and the adult cicada emerges from its brown skin, unfolding delicate wings that are pumped full of fluid as they unroll and harden. The shed skins, or ‘nymphal exuviae’ remain behind, clinging motionless and empty to a fence post, evidence of the adult cicada’s arrival above ground in the night.

The adult cicada usually only lives for two to three weeks. Males call to attract females, who fly to the male chorus and land within 50 cm of the male.The female produces a pheromone which is distributed by wing-clicking. The male responds by changing to the courtship song, before moving towards the female and mating. The female cicadas lay eggs in the live branches of plants that are suitable for the larvae, which hatch and climb down below ground.

For many years, I’ve pondered a strange, intermittent clicking noise heard in summer in the suburbs of Brisbane and here in Toowoomba. The clicking was recently described by a naturalist mate, who had also heard them, as ‘like the sound made by two Aboriginal message or song sticks clacked together’. A perfect description. Advice from those who study insects and like stuff has pointed me towards another green cicada as the likely suspect — the Bottle Cicada (Glaucopsaltria viridis). This cicada has a long, whistling sound on dusk, but is known to produce some intermittent clicking sounds during the day.

Bottle Cicadas are about 3 cm long. The male has an inflated hollow abdomen. They are found in south-eastern Queensland and northern New South Wales. Their main song is a continuous, monotonous whistle at dusk, between October and April.

It’s taken years, but I finally found one of these insects. While walking on dusk past a hedge from which I’d previously heard the mysterious clicking, I noticed a long whistling call emerging from all over the hedge. Closing in on one source of the sound, an insect flew down to the ground, where my faithful fellow-naturalist dog tried to eat it. I wrestled the insect from the dog’s mouth, and found that it was indeed one of these green cicadas. I had at last solved my personal mystery of the weird clicking sounds.

Bottle Cicada. Cicadas have two obvious, large, compound eyes, and three ocelli. Ocelli are jewel-like eyes situated between the two main, compound eyes. It is thought that ocelli are used to detect levels of light and darkness.

Some naturalists are dedicated to investigating, and recording and analysing, the sounds of nature. Sid Curtis describes on the Nature Recordists forum his investigation into the clicking call of Bottle Cicadas, using some specialist microphone and and recording gear:

Here in Brisbane the Bottle Cicada is common in our suburban gardens. Like many cicadas, the males all sing at the same time, thus making it difficult to locate any one individual. With just one’s ears, that is. Klas’s so excellent and highly directional Telinga mic and reflector make it easy. They sing at dusk: “Continuous and without apparent variation”, is how Dr Max Moulds author of the book Australian Cicadas, describes it. But that is not all.

During the day they have a very different and far-from-obvious call. Just a few (up to 5) short sharp ‘bips’ over a second or so. Then silence for several minutes. Also very effective in making it difficult to locate the insect by the sound. (And incidentally, using Peak LE software and a Mac computer, I have strung these bips together without spaces between them, and produced their continuous dusk song.)

To locate one during the day, play a recording of the continuous dusk song, and the cicada just has to join in. He won’t keep going for long after you stop the recording, but you can start him again. The dusk song of course is to attract females for mating. The song changes if a female arrives. I surmise that the intermittent day song is aimed at males — to enable each to maintain his personal space. I hoped to test this by concealing a small speaker fairly close to a male and playing a recording of the spaced-out day song. Unfortunately my garden is very small; I’d have to use the garden next door. This was a possibility but the house was sold and the new owners cleared the whole area — all trees and shrubs have gone, and there’ll be no cicadas.

But back to mechanical noise. At one stage someone used a motor-mower with

a whine of just the right pitch to match the cicadas dusk song. And they

joined in!

Now, I’ll need another mystery of the natural world to solve. Luckily, there are zillions more out there!

Links:

- Queensland Museum information sheets on Australian cicadas.

- A tricky question about cicadas.

- Inside the life-cycle of Australian cicadas.

Also see my earlier post on cicadas here.