Managing fire is a constant part of a Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service ranger’s job in Queensland.

While photography isn’t high on the agenda for those involved in the business of working closely with fire, rangers sometimes capture dramatic images of flames and burning landscapes.

Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service officers working controlled burn, Pine Ridge Conservation Park, 2013. Photograph courtesy Josh Hansen, QPWS.

Burning log, late afternoon on a planned burn, Bulli State Forest. Photograph courtesy Brett Roberts, QPWS.

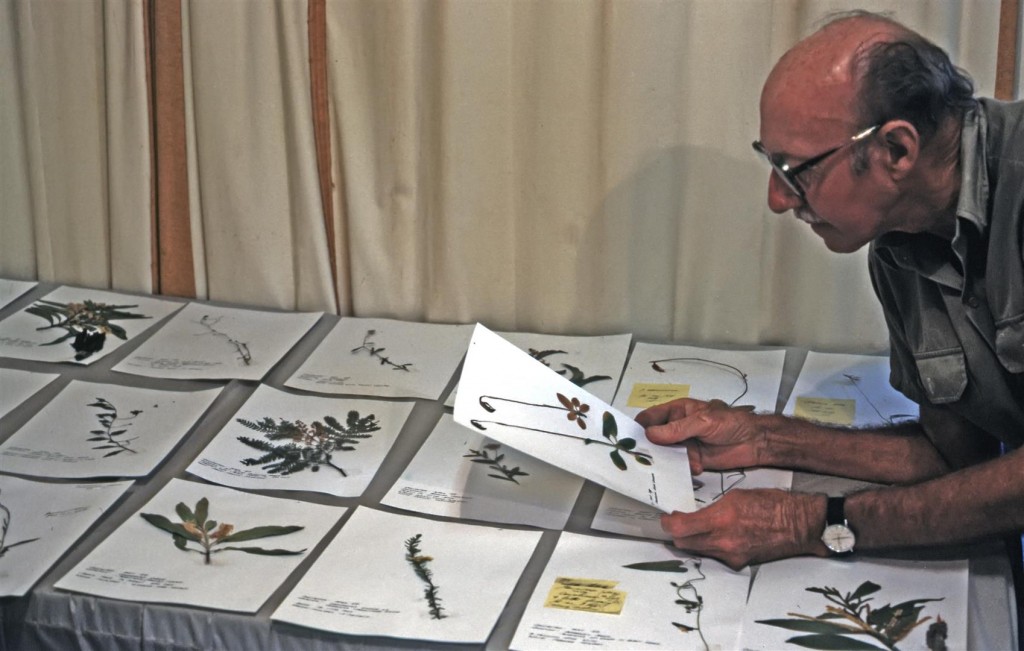

The late Bill Morley was a ranger at Carnarvon Gorge National Park for over 15 years. He was also a keen photographer and naturalist, compiling a large slide collection and recording detailed notes on natural history at the gorge.

Bill Morley camping in Lethbridges Pocket, Mount Moffatt, before the area was declared a national park. January, 1979.

I recently undertook some archival scans of Bill’s collection of Kodachrome slides taken during his time at Carnarvon. Included in the collection is a record of a large wildfire event at the Gorge in 1988. The images are impressive — well composed and often taken in difficult conditions — even more so considering that they were taken while fighting the fire with other rangers. In the end, the fires ran for 53 days and burnt out over 80% of the park.

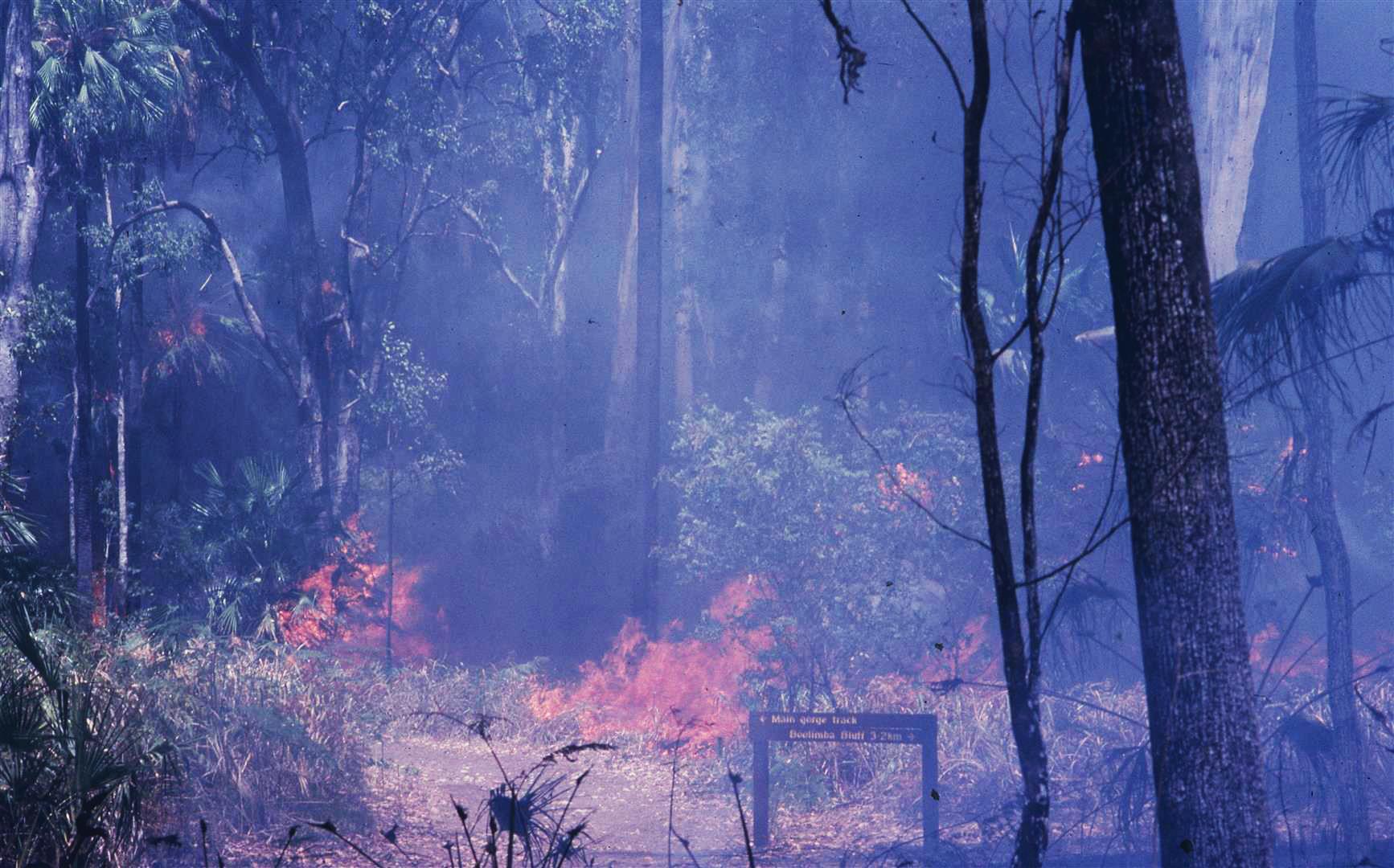

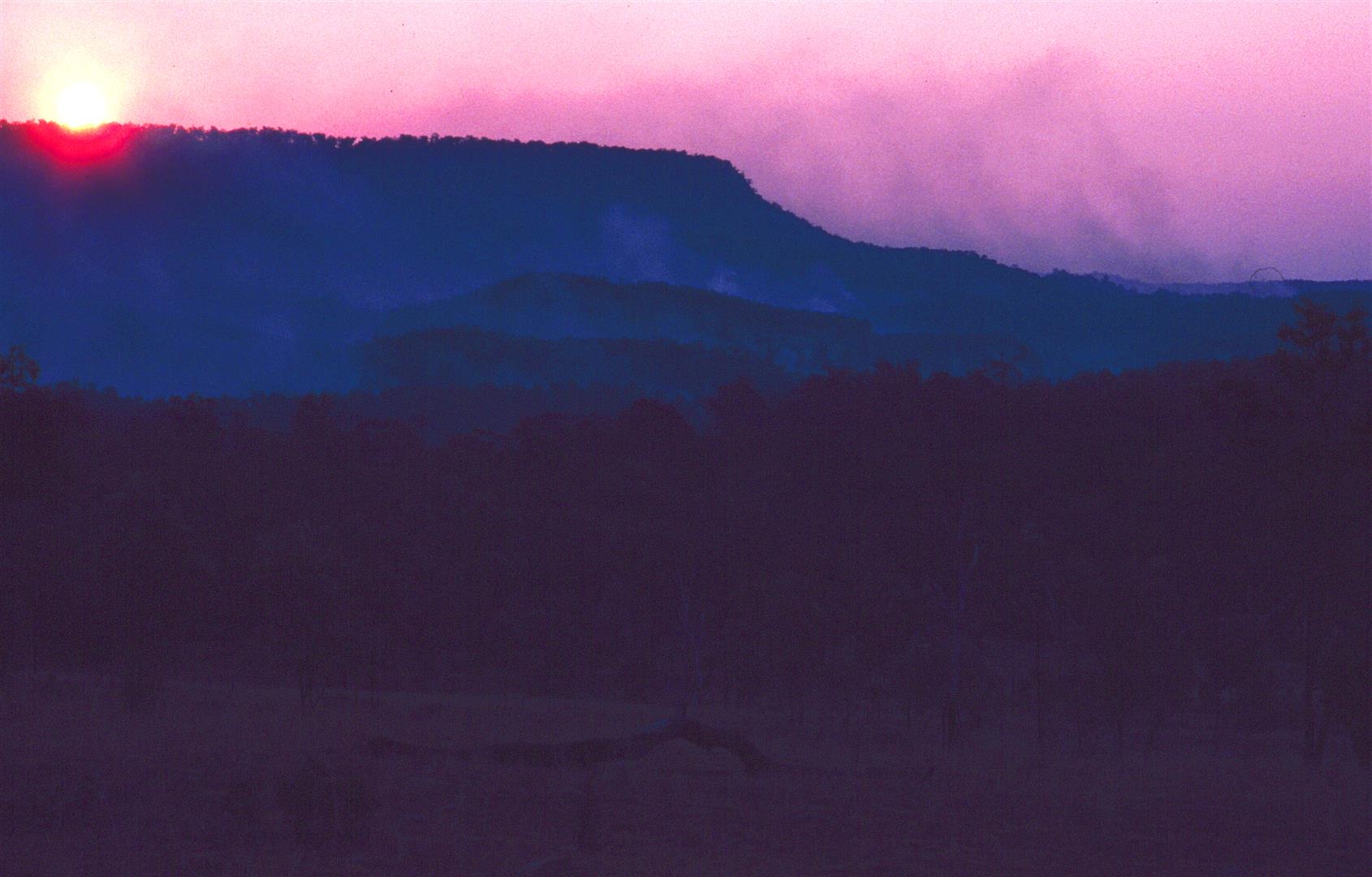

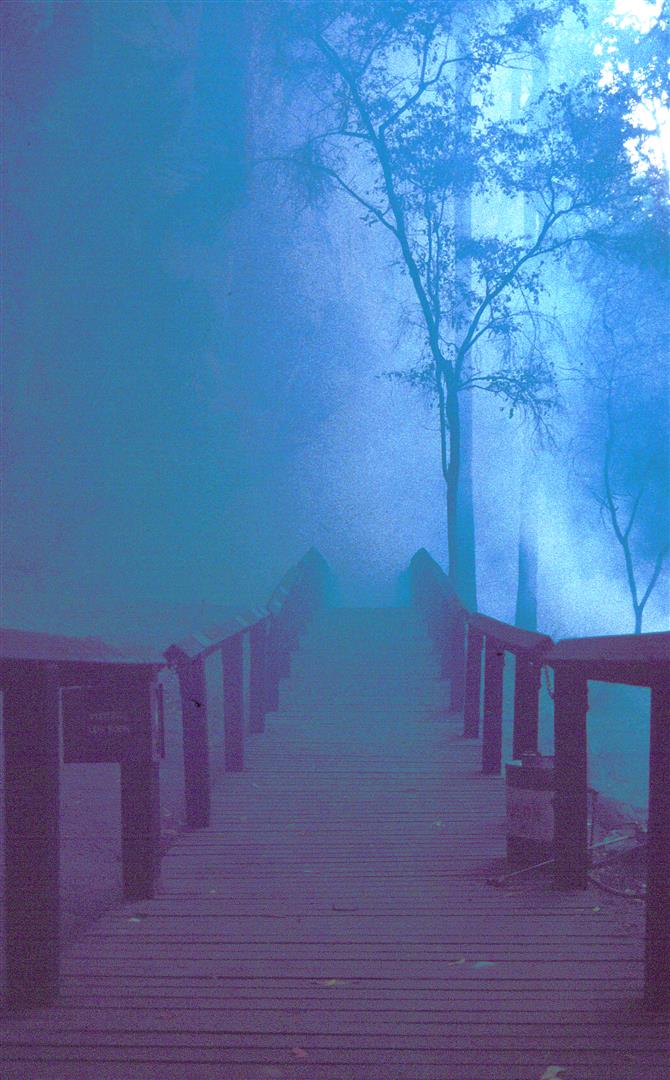

Here is a small selection of Bill’s images of this 1988 wildfire (which I have restored from slides affected by dust and fungus), accompanied by extracts from the notes he subsequently put together for a slideshow on the fire for future park visitors.

What can be done when a wildfire starts in rough country like this? It had been a good season up until the end of September 1988. But, with the coming of October temperatures soared to around 39°C in the shade. Hot winds blew, and humidity dropped, The green grass became brown and brittle, and the softer plants and shrubs wilted in the relentless heat.

Midday, Sunday 16 October. A lightning strike during a dry storm started a fire in dry grassland and leaf litter on a rocky ridge above Mickey’s Creek gorge, and, although it wasn’t known at the time, another lightning strike from the same dry storm started another fire near the extreme north-east of the park. There would soon be two wildfires in Carnarvon Gorge National park.

From vantage points both inside and outside the park, rangers took bearings of fire positions. Contact was made with neighbours and information exchanged on the positions and progress of the fires, Spreading rapidly, the fires in the south-east section dropped down into Mickey’s Creek Gorge, whilst up on the cliff edge, fierce winds caused it to ‘crown’ in the tree-tops in many places. That night, park rangers burnt back along the southern edge of Mickey’s Creek walking track, to contain the fire front the for the time being.

The next day the fire in Mickey’s Creek Gorge was heading eastwards toward the walking track and the fire at the top of the cliffs was spreading fast. Carnarvon Gorge Lodge and Bandana Station grasslands were under threat from advancing flames. Walking tracks in the gorge were now closed to park visitors.

The fire had dropped off the eastern edge of the Goombungie Cliffs, so a back burn from the western edge of the Baloon Cave track was undertaken to neutralise that firefront. Just on dusk, above the cliffs, flames raced up the steep slopes of the Great Divide and hit the top edge of the eastern side of ‘The Ranch’.

Visibility became severely restricted at times, as the Carnarvon ranges were absorbed within a huge blanket of smoke. At times, several palls of black smoke could be seen within the overall greyish-white, markings of the second fire now racing across the south-central section of the Consuelo Tablelands towards Carnarvon Gorge, pushed by strong north-eastern winds.

The next day, thick palls of black smoke signal that the fire is almost at the edge of Warrumbah Cliffs, immediately behind the national park’s workshop area. Cliff-top winds and updrafts contribute towards fire crowning in the trees along the cliff edge. Back-burns continue throughout the next two days to control the fire’s advance.

Eight days after the fires began, a few millimetres of rain is recorded, dampening the vegetation and quietening the fires temporarily, but three days after the rain any moisture has evaporated and the fires are whipped up again by steep winds.

Fire on no fire, it’s business as usual in the camping ground, the people still come. Four large coaches are parked in the coach zone which is filled to capacity. Not many family campers arrive, as campers are discouraged from coming until the fires are out.

Thirteen days since the fires began, and the floor of the inner gorge is aflame and once again a park ranger is stationed at the Art Gallery, and another at Cathedral Cave. A back burn commences to save the cypress pine board-walk from the approaching flames.

Sixteen days after its birth, fire moves in behind Boolimba Bluff and drops over the edge in many places.

The remnants of the fires are still going 53 days after their start, when the first good storm occurs, with 75mm of rain. All fire is extinguished in the gorge. Loose soil is washed into creeks and Carnarvon Creek runs a deep chocolate colour, with black ash and charcoal floating on top. A tiny glimpse of the ever-ongoing process of erosion that, over a long time period, changes landscapes.

The rains caused the grass roots to sprout juicy green shoots and the kangaroos and wallabies feasted, and nests are built by birds as new leaves sprout in fire-singed trees and the insect population increases. A dazzling green rebirth follows, until the next fire.