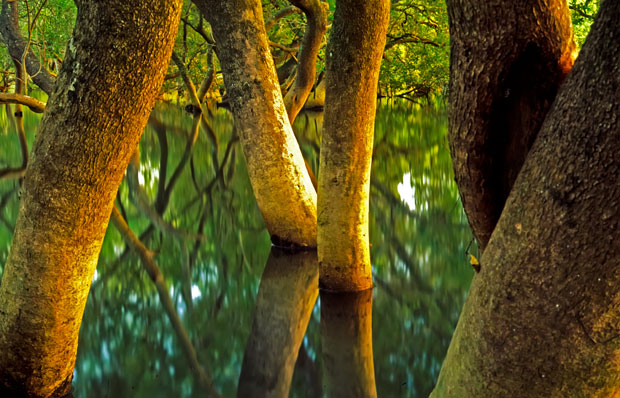

Young Osprey (Pandion haliaetus) fishing. Cornmeal Creek, Sunshine Coast. Photograph copyright Ross Naumann.

Photographer Ross Naumann has captured some superb images of two young Ospreys (Pandion haliaetus) fishing in a creek that runs through the middle of a large shopping complex at Maroochydore on the Sunshine Coast.

Ross reported that locals stopped to watch the raptors fishing in one of the Sunshine Coast’s busiest shopping precincts. The local papers carried a story on the birds and Ross’s wonderful photographs.

Photograph copyright Ross Naumann.

Photograph copyright Ross Naumann.

Photograph copyright Ross Naumann.

Such magnificent (and skillfully taken) images remind me how fortunate we are to be able to see ospreys so closely. This hasn’t always been the case around the world. Here’s an article I wrote about ospreys many years ago for a local wildlife newsletter.

Lasgair – the Fishing Pheonix

Osprey! We looked up from the shining water of Tingalpa Creek to see the bird moving towards us. A visiting wildlife photographer friend from Sweden, Ulf Westerberg, had expressed a wish to see some local birds, particularly ospreys, so we were off up the creek at high tide in mate Simon Grainger’s small tinny. To our astonishment, as the bird approached it suddenly folded its wings and dived straight at us. Despite having at least three cameras between us in the boat, all that moved was our jaws as they fell open in surprise. Talons outstretched, the bird rocketed directly toward us, bright yellow eyes clearly staring ahead. With a huge splash the osprey slammed into the water, no more than two metres from the boat, showering us with water. It then floated for several seconds, looking calmly at us, before hauling itself out of the water and flapping off. It had missed the fish, and was soon travelling away from us, looking left and right for other dinner chances in the water below. We burst into loud laughter and shouts of amazement. “Yes,” I’d said earlier “perhaps we just might see an osprey.”

We are fortunate to have such exciting birds sharing our local fish with us. Despite some persecution, they have not been threatened with extinction in Queensland. As I recently had the good fortune to be doing some raptor spotting in Scotland, I found out a little about the story of the osprey over there. It’s an incredible tale of despair and tragedy leading to unlikely success.

There are four sub-species of osprey distributed throughout the world. The Scottish osprey is a different sub-species from ours, but is very similar in appearance. Their Scottish name is Lasgair, which means ‘fisherman’. Scottish Ospreys migrate to Africa during the northern winter, returning to breed in spring. In the 1800s, ospreys were shot by landowners, and the ‘naturalist-hunters’ killed adult ospreys and took their eggs. There was a market for their skins (for display cabinets) and their blown eggs (for egg collections). Typical of the time was this effort by Lewis Dunbar:

On the 3rd May 1851, Dunbar arrived at Loch an Eilein, near Aviemore in Scotland. He had walked many miles through the night. Quickly, he slipped into the icy water and swam to a deserted castle on an island in the loch. As he climbed the castle, six inches of snow covering the ramparts slowed his progress. Eventually he reached the top, where there was an osprey sitting on eggs. Chasing away the bird, he grabbed the eggs and climbed back down. Dunbar then swam to the shore, an egg in each hand. There, he then blew the eggs, washed them out with whiskey, and eventually sold them to collectors.

As a result of events like this, ospreys became extinct in Ireland in 1800. In England, they vanished by 1842. By 1848, there were only 40 – 50 pairs left in Scotland. On 17 May of that year, two collectors, Charles St John and William Dunbar (Lewis’ brother), met at Loch an laig Aird, a known osprey nesting location. They arrived to see a female osprey in the nest. St John shot the female as she flew past. The male returned, and St John wrote, “he flew around, plainly turning his head to the right and to the left as if looking for her, and as if in astonishment at her unwonted absence.” As St John and Dunbar left with the two eggs and the body of the female, St John recalls, “the male bird unceasingly calling and seeking for her. I was really sorry I had shot her.”

Despite the efforts of beleaguered osprey fans at the time, 1916 saw the last pair nest in Scotland. They were not seen again after that year. I wonder how those few osprey protectors felt — their efforts had been to no apparent avail.

Fortunately, the story does not end there. In the 1950s, due to protection by bird fans, osprey numbers in Norway increased, and in 1953 a pair travelled from there to Loch Garten in Scotland. Osprey fans rallied, but egg collectors robbed the nest. The same thing happened during the next two years. In 1957, the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds organised volunteers to watch the nest around the clock, but one of the adults was shot travelling to the nest. In 1958, after a pair of ospreys arrived, Operation Osprey swung into action — just in time, as an egg collector was caught climbing the tree immediately after the female laid eggs. A team of volunteers worked around the clock, but on a dark and stormy night another thief climbed the tree and took the eggs. It caused headline news, and a tide of public sympathy began to flow in favour of the birds. The area was declared a sanctuary, which made it illegal to enter the land without permission. In 1959, a huge army of volunteers camped at the nest tree. Their efforts were successful — young were hatched, and the warden George Waterson took the brave and risky move of opening an observation post for the public. In the seven weeks until the young flew, 14,000 people flocked to catch a glimpse of these birds!

Today, the nature reserve at Loch Garten has been extended to 30,000 acres. Until 1991, 58 young were raised at this nest, but not without problems – the observation post was burnt down in 1991, and the nest tree has been attacked three times. The site has become famous. Press, radio and television report each year’s arrival of birds. Road signs declare that “ospreys have arrived” or “eggs laid!” In the last three decades, over one and a half million people have visited the site! Around the country, 836 young ospreys were raised to 1991. Once again, ospreys travel to Africa, and arrive back in Scotland to breed. The efforts of those original osprey protectors were actually never really in vain. Their actions influenced others, and as attitudes changed, many people were able to rise to the defence of these great birds when they finally returned to Scotland.

Jim Crumley, who has worked for most of his life protecting ospreys in Scotland, recalls those past times there when all was threatened by “the lunatic fringe of our species”. He writes:

There were the early days of through-the-night watches in a flimsy, leaky tent, armed with spotlight and megaphone to fend off intruders (they were used twice, and actually worked) … there was the otter which swam past my feet at 4am, and the barn owl which cruised out of a morning mist on a collision course for my head — we both took evasive action at about ten feet apart. And there is one unforgettable image of the female bird standing on her nest at sunrise, to stretch her wings and cast off accumulated night rain and dew. This she did with the blood-red sun at her back, so that she showered the eyrie-tree with shed drops of fire. No phoenix ever rose with more panache.

Photograph copyright Ross Naumann.

All images courtesy of, and copyright, Ross Naumann. Please respect the photographer and do not use images without permission.