A rogue’s gallery of some of the wild characters I’ve had the pleasure of meeting at Carnarvon Gorge over the last few years.

Mouse spider

When people come across a large black spider they often think they’ve encountered a Funnelweb Spider. However, not all large black spiders are necessarily Funnelwebs.

I recently had the opportunity to photograph this spectacular Red-headed Mouse Spider (Missulena occatoria), dropped off to the QPWS office from Oakey, on the Darling Downs in south-eastern Queensland. This spider was a female — the males have a deep red head and royal blue abdomen.

Mouse spiders are related to Funnelwebs and Trapdoor Spiders. They are all members of a ‘primitive’ group of spiders, from the Infraorder Mygalomorphae. These are among the largest and longest-lived spiders, and one of the oldest groups of spiders found in the fossil record. They have remained almost unchanged for tens of millions of years.

One of the things that is so special about macro photography is the wonderful detail in the resulting photograph that was often missed with eyes alone, especially when you’re reluctant to get your face too close to the subject! I love the fine red-hairs and the colours in the leg joints of this fabulous arachnid.

The Queensland Museum (QM) website is a great source of information on Queensland spiders. They report that three species of Mouse Spider have been recorded in Queensland:

- Redheaded Mouse spiders (Missulena occatoria)

- White-backed Mouse spiders (Missulena bradleyi)

- Small Black Mouse Spider (Missulena dipsaca).

Mouse Spiders are often confused with Funnelweb Spiders. There are differences in their morphology, although to see this might require a fair bit of care and courage if you’re not particularly enamored of our eight-legged wildlife (“Sit still, I need to see where your eyes are!”).

When viewed from the side, the head of the mouse spiders appears as a step, strongly divided into two levels by a nearly vertical drop from the front half of the head. The eight tiny eyes are spread across the front of the upper section behind the very prominent chelicerae. In funnel-web and all other trapdoor spiders the eyes are grouped together on a mound at the centre front of the head and the head is not strongly divided. — QM

Mouse Spiders are apparently quite common in many Queensland suburbs, but not often seen. From the QM website again:

They make a very well concealed burrow in the lawn or open ground. Often the web tube flops onto the ground and is soil-encrusted and hence well-camouflaged. Burrows may be located in lawns after rain by looking for small pyramids of soil beside which is a very well concealed tube.

The spiders are often found while gardens are being dug or soil turned over. Males wander from late Summer and tend to peak in April-May and often fall into suburban swimming pools whilst searching for females.

There is ongoing research into these spiders and just how venomous they are. A recent confirmed bite to a young girl from one of these spiders caused a severe reaction. However, the girl recovered after receiving Funnelweb antivenin.

The Queensland Museum mentions the enigmatic nature of these spiders and what is known about their venomous nature.

The seriousness of the bite of Missulena was until recently the subject of serious disagreement. We had recorded several reports of uneventful bites from Missulena species both males and females. Two reports stand out. In one, a 7-year-old boy had a female Mouse spider attached bull-terrier style to his finger. The GP had to crush the spider to get the fangs out. The boy complained only of minor hunger pains as in the excitement, lunch had been missed!

The second case was of a paramedic whose earth basement was almost swarming with male Missulena bradleyi. He was bitten repeatedly by the males in his sleeves. The immediate pain soon passed and he had no problems until 36 hours later when a large infected area appeared on his arm. He applied an antibiotic powder and the wound healed and was barely noticeable when we saw it a week or so later.

The late Dr Struan Sutherland’s research showed that these spiders were potentially more toxic than Funnelwebs; thus, we were at odds. Inexplicably, the Gatton baby recovered quickly when given Funnelweb antivenom. Clearly, the Gatton bite was what Sutherland had predicted but why did some victims not react?

Dr David Wilson, then at the Department of Drug, Design & Development, University of Queensland looked at the question. When Funnelwebs disturbed, they quickly rise to the defence pose with a drop of venom on each fang tip. However, although Missulena also rises to the defence pose quickly, venom is rarely seen.

It seems that the Mouse Spider rarely needs or uses its much smaller reserve of venom; presumably most of the uneventful bites were dry, i.e., without venom.

Links:

- An earlier post on Funnelwebs and other spiders around Toowoomba.

- The Queensland Museum spider pages.

- Dr Robert Raven talks about Funnelweb Spiders.

- Australian Museum — Mouse Spiders

… and some more frogs

I recently stayed one night at Girraween National Park while on a work trip, and it was a stormy summer night. Perfect, of course, for checking the frogs around Bald Rock Creek!

There’s one species of frog at Girraween that I’ve never seen — the New England Treefrog (Litoria subglandulosa). Classed as ‘vulnerable’, this fog is only found in a small area of wet sclerophyll and heath country in the granite country of the Queensland/New South Wales border. To see an image of this beautiful species, check out this great image on this wonderful website on Girraween National Park.

Meetings with remarkable frogs

Any little dam or pond on a summer’s night, as long as it has some water and a bit of vegetation around it, can be a magnet for the frog-photographer (yes, there is such a niche in photography).

On a weekend escape with the family, as we sit on the verandah of rented cabin enjoying the fading late-afternoon light, a chorus of weird noises drifts up from a small dam just out of view, on the edge of some bush. Frogs!

I’m instantly trying to identify the callers, a habit formed many years ago when summer nights were often spent in the somewhat eccentric pastime of lurking in a muddy, mozzie-ridden swamp trying to find some tiny frog, while clutching cameras, flashes, cables and other paraphernalia.

Eastern Grey Kangaroos, and a single Red-necked Wallaby , hanging out on a slowly-cooling afternoon, and probably trying to identify the species of frogs they can hear calling.

I’m travelling a bit lighter with camera gear these days. I grab my Olympus OMD-EM1, a 60mm macro, a single flash with off-camera cable and head down to the dam to take a look.

I’m soon reminded that it’s always harder to find frogs than I remember.

A racket of various sounds assails my ears as I approach the dam, which is surrounded by vegetation and covered in water-lilies. Where to start? I pick a weird little ‘riiiiiiik’ sound in the grass and sneak up on the culprit.

Of course the frog hears some monster with the sun strapped to its head approaching noisily and, sensibly for a small vulnerable amphibian, stops calling. It seeks a mate, not some huge predator, and has no desire to be the subject of a dodgy blog post by some nocturnal swamp-wandering weirdo.

I move on to the source of another of these sounds, only to have the same thing happen. Soon, I’m heading off to nowhere, no closer to finding the tiny frog. If a fellow frogologist, sorry, herpetologist, was present, we could triangulate and move to the meeting spot of pointed fingers. X marks the spot. A secret frog-finding technique I learned from the Frog Photography Guild in my local chapter of the Illuminati.

However, I’m on my own tonight, as there was no chance of convincing wife and teenage son to attach head-torches and help me. They’ve been there before, remembering epic all-night expeditions that started with an innocuous “Can you help me find this frog?”. They are more interested in finishing a game of Simpsons Monopoly (yes, there is such a thing).

When you’re on your own, you soon realise that frogs are amazing ventriloquists. They are never where their calls seems to indicate. However, I persist, returning to the first caller, and eventually spot the lurking little character. He’s a member of the genus Uperoleia, a frog group known commonly as Toadlets or preferably to me, Gungans. There are currently ten known species of these small frogs in Queensland, and they are all hard to identify to species level. I think I’ve found a Uperoleia rugosa, the Wrinkled Toadlet or Chubby Gungan.

“Oh no, the swamp-wandering weirdo has found me!” Chubby Gungans are about 3cm long and are great ventriloquists.

There are other tiny things wandering about at night, including this colourful spider.

There are other tiny things wandering about at night, including this colourful spider.

One of the dam-side calls is quite distinctive, It’s a loud, manic, descending cackle — the laughing call of the Emerald-spotted Tree Frog, Litoria peronii. This is one of my favourite animals, a true character. It always make me smile when I hear their ridiculous call.

One of the dam-side calls is quite distinctive, It’s a loud, manic, descending cackle — the laughing call of the Emerald-spotted Tree Frog, Litoria peronii. This is one of my favourite animals, a true character. It always make me smile when I hear their ridiculous call.

It’s a bit hard to see the bright green spots on this frog, but they are there. They have wonderful bright yellow and black markings inside their hind legs. This is one of three similar species in Queensland that have green spots.

A sudden movement catches my eye as a frog leaps through the air in front of me. I track it down. It’s a Broad-palmed Rocket Frog, Litoria latopalmata. This species makes a series of rapid ‘quacks’ that accelerate then slow down.

A loud ‘bonk’ sound leads me to another favourite frog — the Eastern Banjo Frog or Grey-bellied Pobblebonk, Limnodynastes dumerilli. Limnodynastes means something like ‘Lord of the Marshes’.

One frogologist describes their call as ‘reminiscent of PVC pipe being struck by a rubber thong’. How would you know that? I guess you’d have to try it. Eccentric lot indeed. Pobblebonk, their other common name, is a great interpretation of the sound a bunch of these make when calling at once.

The most persistent call in the froggy racket is an almost deafening rasping, rickety call. Small green and brown frogs cling to feeds or occupy lily pads. These are delightful Eastern Sedge Frogs, Litoria fallax. Each frog is slightly different, their colour various combinations of greens and browns. They are like tiny jewels. I like them a lot.

The most persistent call in the froggy racket is an almost deafening rasping, rickety call. Small green and brown frogs cling to feeds or occupy lily pads. These are delightful Eastern Sedge Frogs, Litoria fallax. Each frog is slightly different, their colour various combinations of greens and browns. They are like tiny jewels. I like them a lot.

There’s at least one other species calling. I’m pretty sure it’s a Clicking Froglet, Crinea signifera, or possibly a Beeping Froglet, Crinea parinsignifera. I’m too tired to catch it, so here’s a pic of a Beeping Froglet I found one night in a road-side swamp in Texas, southern Queensland. It’d look something like this from a prone position in the mud (how I met this one).

As I sloshingly return to the Monopoly players (Homer has been rendered bankrupt by Margie apparently), and the calls of the unfazed frogs fade behind me, I reflect on the many memorable meetings I’ve had with these critters over the years.

It may indeed seem odd to some, but I’ve enjoyed the moments spent with such mysterious and ridiculously enchanting amphibians in the bush at night. I count myself lucky to have met them. Long may we have such wonderful things out there somewhere in the darkness busy being themselves.

Here’s a quick rogue’s gallery of some of the frogs I’ve tracked down over the last few decades.

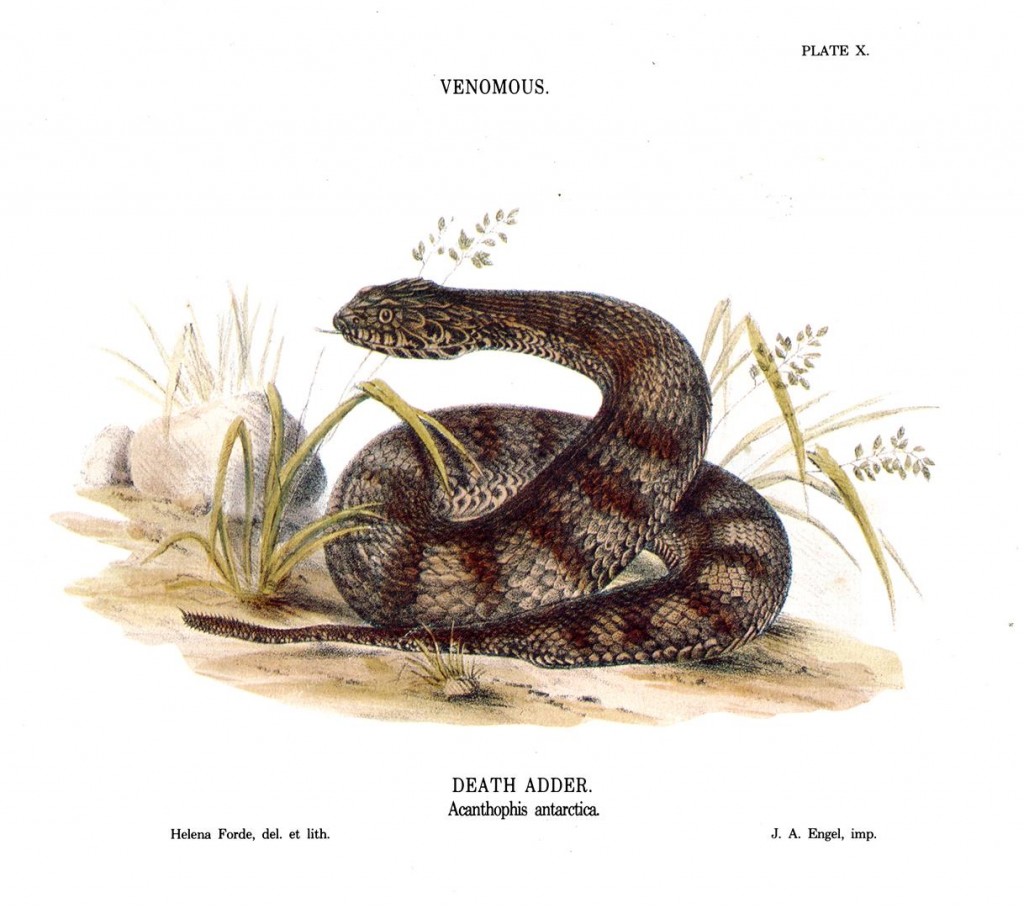

Australian adders

The Death Adder is one of Australia’s more unusual snakes. This post presents some recent photos of this reptile from around Queensland and northern New South Wales.

Maree Cali from Mackay spotted one of these highly venomous elapids close to her campsite. Says Maree, “I was excited to accidentally set up camp over the Easter break next to this cool customer and was blown away by its laid back nature, camouflaging ability and beauty — and I’m not particularly into snakes.”

Gerry Swan and Steve Wilson give an overview of Death Adders in their book What Snake Is That?

Australia is the only continent with no vipers, family Viperidae. In their absence, some elapid snakes of the genus Acanthophis have evolved to fill a similar niche. These sluggish, well-camouflaged and sedentary snakes lie concealed in leaf litter or under low shrubs and grasses. Important features of this group are a short, thick body, a broad head distinct from the neck and an abruptly slender tail.

Their similarity to vipers was not lost on early settlers, who were reminded of the Adder (Vipera berus) from Britain and Europe. They named the Australian snakes ‘death adders’ because of the high mortality from bites before anti-venom became available. The corruption ‘deaf adders’ may derive from their reluctance to move away when disturbed.

Death Adders are ambush predators that feed on a variety of vertebrates. The slender tail has a segmented tip and soft spine, and they lie with this resting near the head, When prey is detected, the snake wriggles the tail convulsively, mimicking a grub or worm to lure the animal within striking distance. Its ability to strike so suddenly and with such mind-boggling speed is unnerving to witness, particularly considering the snake is slow moving and prone to lie motionless for days on end. The strike is accurate and lethal, as a powerful venom is injected deeply through long fangs.

Death Adder, with strikingly patterned head strategically positioned near its tail (aka caudal lure!). Captive specimen, photograph R. Ashdown.

Common Death Adder. From The Snakes of Australia, by Gerard Krefft, 1869. Death Adders are not true ‘adders’, belonging instead to the same family as other venomous Australian snakes, the elapids. Their similarity to adders, which are actually members of the viper family, has evolved in response to the species’ environment and their ‘sit and wait’ style of life, which does not require a snake to be long and agile but short and muscular for a quick strike when necessary.

Kate Steel encountered a Death Adder near her back verandah of her house in northern New South Wales. Kate relocated the snake in a sack, grabbing a few photos on the way. She posted on Facebook, “Just caught this slithery under the verandah, there was a Willy Wagtail giving warning and then Lyly the alarm dog. Hope the photos are not too shaky cos my hand is!”

A Death Adder being relocated from near the back verandah to somewhere less likely to be trodden on by bare feet. Photo by Kate Steel.

Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service (QPWS) Rangers often encounter snakes as part of their daily work. Ranger Stuart Fyfe took the following photos of a Northern Death Adder (Acanthophis praelongus) in far northern Queensland.

“I found this Death Adder pretty late one night outside the barracks common room, (around 11pm), so took a few photos then put him in a bucket to relocate him in the morning. We have a couple of families on base with small kids, so we tend to relocate these guys down the track.

When I first found him he was quite docile, and didn’t puff up even when I put him in the bucket, but when I released him in the morning he was all fired up — they tend to puff up like that when they are being defensive. He must not have liked being in the bucket overnight.”

Death Adder moving out of grass to escape a controlled burn on national park. “This was one of the biggest we’ve seen up here. Based on the width of the Rake Hoe I estimate he was about 42cm long.” — Stuart Fyfe. Photo by David Delahoy, QPWS.

How dangerous are death adders to humans? From a Wikipedia article that lists details of deaths due to ‘unprovoked bites by snakes’ in Australia:

The estimated incidence of snakebites annually in Australia is between 3 and 18 per 100,000 with an average mortality rate of 0.03 per 100,000 per year. Between 1979 and 1998 there were 53 deaths from snakes, according to data obtained from the Australian Bureau of Statistics.

Between 1942 and 1950 there were 56 deaths from snakebite recorded in Australia. Of 28 deaths in the 1945-49 period, 18 occurred in Queensland, 6 in New South Wales, 3 in Western Australia and 1 in Tasmania. The majority of snake bites occur when people handle snakes in an attempt to relocate or kill them.

Australia is the only continent where venomous snakes constitute the majority of species. Snake bites in Australia that cause deaths are less common than they once were, because of increased medical knowledge and anti-venom that is better and more available. Around half of all deaths from snakebites are thought to be caused by brown snakes, perhaps as many as 60% of deaths caused by snakebite.

Unlike other snakes that flee from approaching humans crashing through the undergrowth, common death adders are more likely to sit tight and risk being stepped on, making them potentially more dangerous to the unwary bushwalker.

However, they are reported to be reluctant to bite. Richard Shine, in Australian Snakes, a Natural History, describes this apparent reticence:

There are many stories testifying to this docility, perhaps the most famous being of two men cutting sugarcane in a paddock. They spent the day working at the job, carrying loads of the crop frequently out of the gate to their nearby truck. It was late in the day that one of the workers noticed a large Death Adder coiled in the dust in the middle of the path, right beside the gate, The dust showed hundreds of footprints from their bare feet within a few centimetres of the snake’s head.

Ranger Andrew Young recalls a family Death Adder encounter when he was a lad growing up on the family farm at Stanwell, west of Rockhampton, in the 1960s. He remembers lots of yelling, and dancing about, associated with this particular snake sighting.

“My Dad had sent the farm-hand out to our other property at Ridgelands where he was to plough up some paddocks for planting sorghum. When he was finished he drove the tractor back to our Stanwell farm for some more work we had there. The farms were about 40 minutes drive apart by car so a good couple of hours by tractor.

When he arrived home that evening we all went to meet him and hear how he went. During the discussion, he said, “Oh, and I found a great legless lizard today!” He opened the tool box on the side of the tractor and hauled out this Death Adder! Dad shouted “Drop it!” and we all leapt back — as you might imagine! I shall not recount the snake’s fate …

But I have always thought that the snake was indeed laid back as it didn’t bite when it was ploughed out of the soil nor when grabbed out of the tool box that it had been jiggling around in all day.”

In its element. A Death Adder photographed in the Mount Moffatt section of Carnarvon National Park by QPWS Ranger Brent Tangey.

Many bites from Death Adders proved fatal before the introduction of antivenom. Death Adder venom contains a type of neurotoxin which causes loss of motor and sensory function, including respiration, which can result in paralysis and death. Deaths from bites are still common in New Guinea.

How dangerous are humans to death adders in Australia? In reality, this snake is perhaps more endangered than dangerous. Despite being labelled ‘common’, the Common Death Adder is becoming increasingly less so. Gerry Swan and Steve Wilson write:

Death Adders have declined in many areas. They can be regarded as biological indicators of environmental quality as they appear extremely susceptible to degraded conditions. Weeds, altered fire regimes, introduced predators and toxic prey in the form of the introduced Cane Toad all play a part in the demise of these snakes from sites where they were once extremely common.

As Steve, who has pursued reptiles across the continent for decades, said to me when talking about Common Death Adders, “I defy anyone to call them ‘common’.”

Reptiles are beautiful and fascinating creatures. They are a fundamental part of Australia’s wonderful biodiversity — something that is under constant siege. Says Steve:

The loss of native vegetation has been the most substantial and urgent problem facing Queensland’s reptiles and other fauna. The estimated annual toll from broad-scale clearing between 1997 and 1999 was a staggering 89 million reptiles, a figure no doubt matched today as hundreds of thousands of the state’s extraordinarily complex natural heritage is bulldozed, heaped and burnt. Apart from the immediate individual casualties, the loss and fragmentation of habitat has implications at population and species levels. With the spectre of increased clearing for expanding coal and gas exports and the push for more northern development, it is critical that habitat continuity be prioritised.

I’m yet to encounter one of these snakes in the wild, but hope the chance to do so will be there for a while yet.

There are five currently recognised species of Death Adder found in Queensland, though several distinct populations may prove to be valid new species. Between these species, Death Adders can be found over most of mainland Australia, except Victoria. All are live bearers, with litters of over 30 young recorded. This is a Northern Death Adder (Acanthophis praelongus). Photographer Greg Watson photographed this captive specimen at Kuranda (within the species’ range and of an animal with a size and the pattern consistent with the location).

Common Death Adder (Acanthophis antarcticus). Photographed on a QPWS fauna survey of Bringalily State Forest by Bruce Thomson

A strikingly patterned Common Death Adder from central Queensland. Photo by Steve K Wilson.

For more information on the five Death Adder species found in Queensland, see A Field Guide to Reptiles of Queensland (second edition) by Steve K Wilson. The book contains some beautiful images of these snakes by Steve and fellow reptile photographers Angus Emmott and Gary Stephenson.

[Safety note: Death Adders are dangerously venomous. All photos on this post were taken at a safe distance. It’s not a good idea to test a Death Adder’s mood by touching one or getting too close with a camera. Seek professional assistance in relocating a snake if you need to move one.]

Thanks to:

- Greg Watson (gregwatsonphotography.com.au)

- Bruce Thomson (www.auswildlife.com)

- Maree Cali

- Stuart Fyfe

- Brent Tangey

- Kate Steel

- Andrew Young

- Rennie Fletcher

- David Delahoy

- Steve K Wilson (www.stevekwilsonreptiles.com.au)

Links:

Around the place

Life on the edge

One perceives a forest of jagged, gnarled trees protruding from the surface of the sea, roots anchored in deep, black mud, verdant crowns arching toward a blazing sun. Here is where land and sea intertwine, where the line dividing ocean and continent blurs. — Klause Rutzler and Ilka C. Feller

If there are no mangroves, then the sea will have no meaning. It is like having a tree without roots, for the mangroves are the roots of the sea. — Attributed to a fisherman from the Andaman Sea

The sun has just risen above Moreton Bay and the sky is catching fire. I’m standing in the incoming tide, in that edge zone where land meets sea. The waking suburbs are less than a kilometre away, but I can’t see or hear anyone. The rising sun doesn’t have my attention. I’m looking the opposite direction, back into a tangled mangrove forest, as the first rays of the sun hit the gnarled grey trunks. Everything in front of me has come together in a brief, quiet spectacle of light and shade, and I’m transfixed by the scene.

———

The edges of things are fascinating places to naturalists and photographers. Ecologists use the word ecotone to describe the edge zone between ecosystems. Landscape photographers revel in edges, the places where the land meets the sky, the ocean meets the shore — where lines draw the viewer into the scene.

With 125km of boundary (stretching from Caloundra to the Gold Coast), Moreton Bay has plenty of edges between land and water. These are diverse places, reflecting the bay’s beauty and contrasts — with mysterious mangrove forests, mud-flats full of life and sandy island beaches. Where the bay stops the growing city of Brisbane in its tracks, the human-built environment swallows these places in walls of concrete or canal estates.

Known as Quandamooka to Aboriginal people, Moreton Bay lies close to Brisbane, one of Australia’s largest cities.

Some of the bay’s gloriously ragged natural edges have been replaced by the geometric patterns of canal estates. It is thought that about 20 per cent of the bay’s mangroves have been lost since European settlement.

Luckily, there are places in Moreton Bay where the zone between sea and land is as it has been for millennia — blurred and hard to define. In 1799 Matthew Flinders couldn’t find the entrance to the Brisbane River because it was obscured by a wall of grey-green mangroves, plants which thrive in the shallow water and mud flats of this island-sheltered bay.

The word mangrove refers to a range of plants growing in the intertidal zone. Orange Mangrove (Bruguiera gymnorrhiza), Coochiemudlo Island.

Mangroves are, of course, important places — as home to marine life, crucial nurseries for the sea creatures our fisheries depend on, and buffer zones to storms and the power of the sea.

Important is a word that just doesn’t begin to cut it. It’s baffling then when we are reminded that some still seem to despise them, as when those who have claimed their patch of real estate by the bay see mangroves as an impediment to their view. Some even destroy them to improve their outlook, killing part of the thing they seek to enjoy, not understanding the basic truth that the bay is a vast living system, with many parts, not just some pretty vista captured within a window frame.

Australia is surrounded by approximately 11,000 km of mangrove-lined coast — around 18% of the coastline, and nearly half of this is found in Queensland. There are about 13,500 ha of mangroves on the edges of the Moreton Bay. Most are found near river mouths and in other areas protected from waves.

A grey mangrove seedling. Nearly 70 per cent of the prawns, crabs and fish we eat depend on the mangrove habitat for at least part of their lifecycle.

Many probably still see mangrove forests as smelly, horrible places crawling with mozzies, snakes, spiders and crocodiles. Explore one though, and light and time slip away. As the sounds of the land fade, other noises are heard — clicks, splashes, the clear piping of a mangrove kingfisher or the sweet, falling leaf call of a mangrove gerygone. There’s a gradual realisation that these muddy, shadowed places are full of life.

So where does the sea actually start or end in a mangrove zone? There’s no set spot of course, this is the intertidal zone, where the water ebbs and flows with the endless tides.

At low tide, old mangroves look like stranded, strange creatures, patterned by lichens and ringed by water-marks. They are partially consumed each day as the incoming tide pushes past them toward the land beyond. In king tides and storms the sea reaches beyond them to saltmarshes and samphire flats, sometimes even popping up in the drains and streets of bayside suburbs like some kind of unwelcome intruder.

On this morning I have waded out before dawn into the mangroves, carrying a camera and binoculars. I’m close to the suburbs but may as well be lost somewhere on Australia’s vast northern coastline, sent back in time to when there were no cities chewing up the bush beyond.

I’ve gone as far as I can, having pushed out beyond the edge of the mangroves.

As the sun rises and the first orange light hits the wall of mangroves, the wind drops and calm descends on the scene, allowing glowing reflections a brief window of life. Realising that this will only last a minute or two, I steady my camera on a shaky, mud-stuck tripod and capture one long exposure. Then, the wind rises, the moment vanishes, and a restless movement fills the mangrove forest as a new day takes over.

Weeks later I get the developed slides back and realise that this single sunrise mangrove image (the first image on this blog post) will be a favourite photograph of mine, one that will have the power to transport me from the stress of busy life to the quiet wildness of the mangroves, still there I hope, greeting each day amid the endless rhythm of the tides, home to myriad creatures, important — and just being its mysterious, magical self.

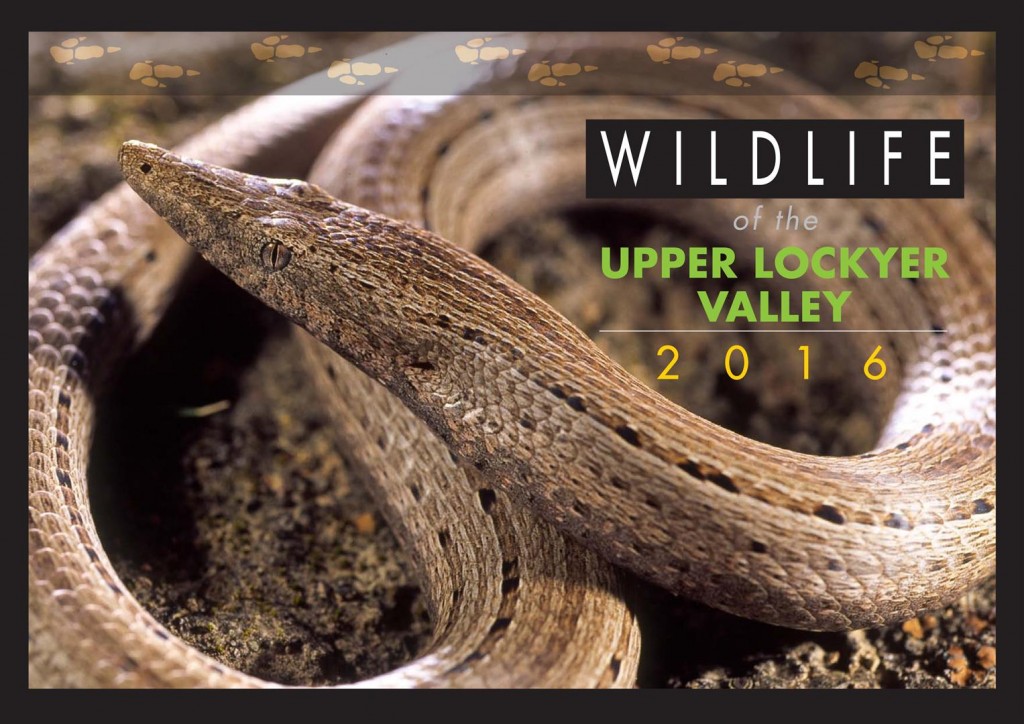

Wildlife of the Lockyer Valley calendar 2016

The Wildlife of the Upper Lockyer Valley calendar for 2016 is now available for ordering.

Proceeds from the sale of this calendar go toward The Citizens of the Lockyer Inc. This community group aims to increase awareness of the rich biodiversity to be found throughout the Lockyer Valley and to promote the adoption of sustainable lifestyles in this unique rural environment.

The calendar features some wonderful images from Bruce Thomson, Mike Peisley and Russell Jenkins (and a few from me), and includes information about the area’s wildlife from naturalist par-excellence Rod Hobson. Design was by the talented Rob and Terttu Mancini of Evergreen Design. The calendar was produced through an Community Environment grant from the Lockyer Valley Regional Council.

Copies are $15 (+ postage) and can be ordered from Roxanne Blackley at bioearth@bigpond.com.

Brachychitons by night

My photographic exploration of these intriguing trees continues.

On a cool evening at Highwoods on the Darling Downs I watched the fading light soak into textured bark. As eerie silhouettes against a starlit sky, these trees seem otherworldly and ancient, reaching silently toward the Milky Way.

[Click on the images for a larger view]

Thanks to Martin, Rod and Mark. See also: Bottle Trees at Highwoods, Brachychiton survivors and Brachychitons Part 2.

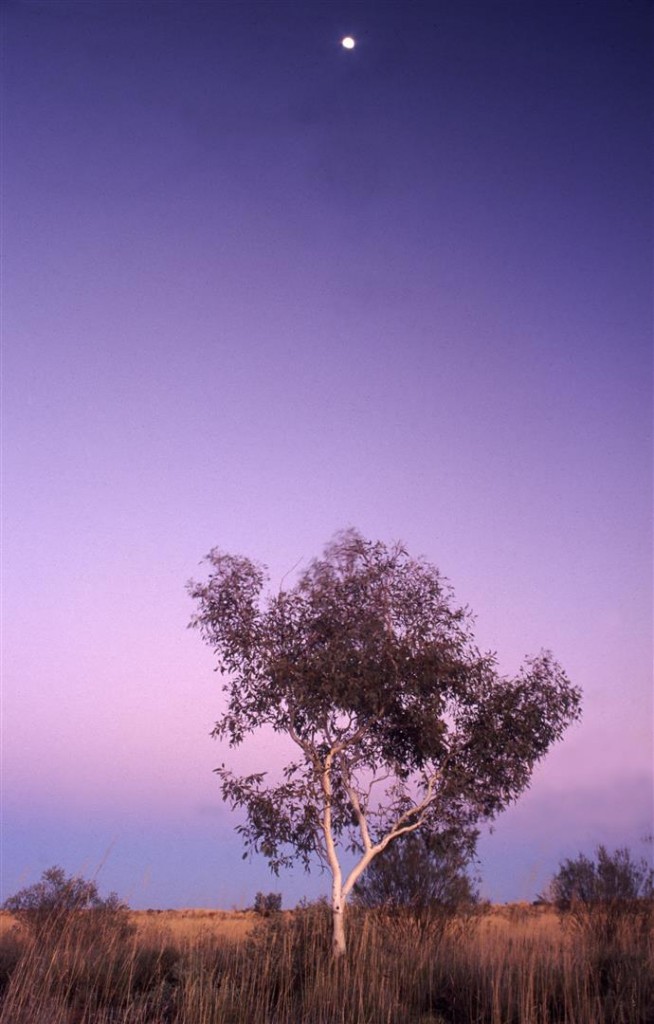

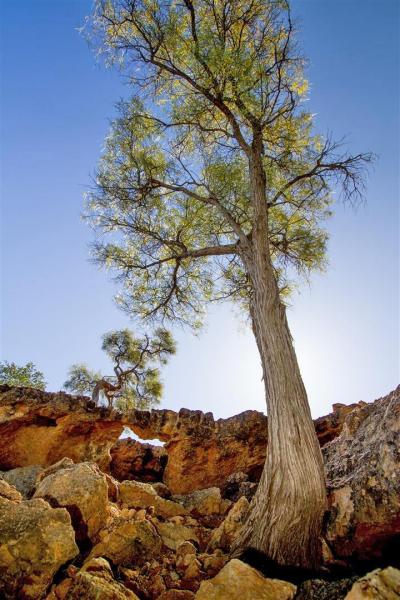

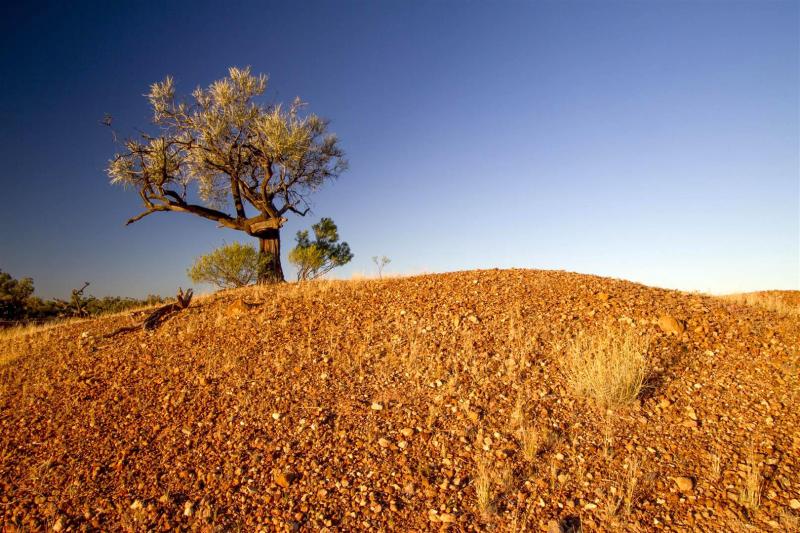

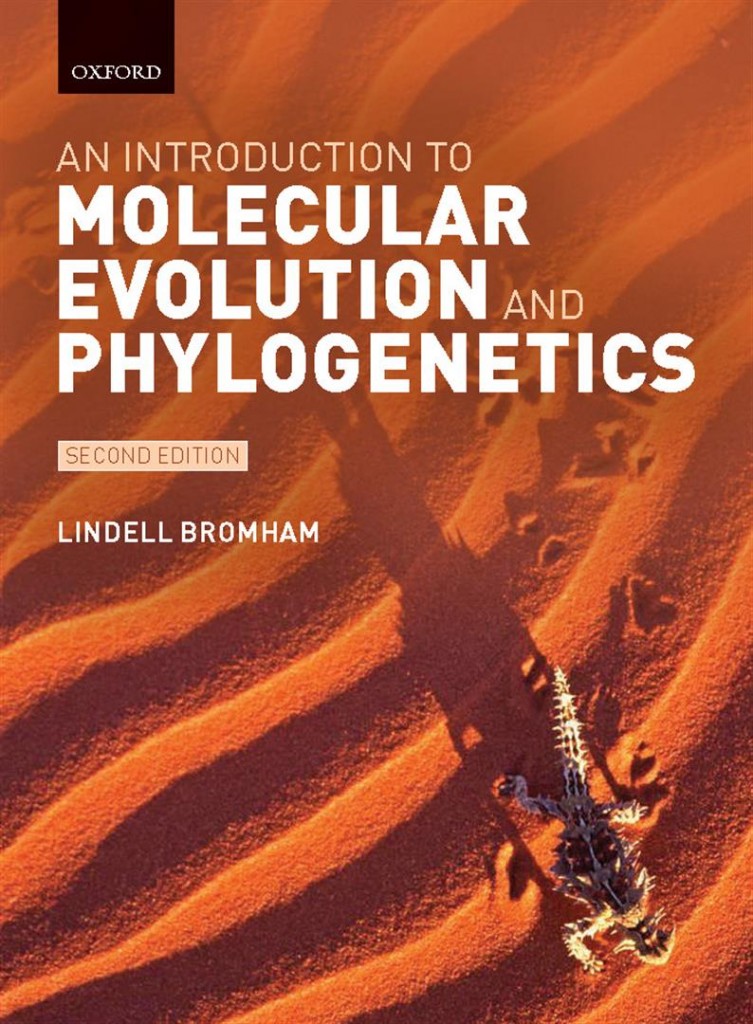

The Simpson revisited

The Simpson Desert. All photos in this post by Robert Ashdown.

The scene was awfully fearful, dear Charlotte. A kind of dread (and I am not subject to such feelings) came over me as I gazed upon it. It looked like the entrance into Hell.

[Explorer Charles Sturt on encountering the edge of the Simpson Desert, September 1845.]

In 1996 I spent some time on the edge of the Simpson Desert. Not much time, and not far into the desert, but it was a memorable adventure.

As an image I’d taken on that trip was recently chosen for the cover of a book on macroevolution (the evolutionary and ecological processes responsible for generating patterns of biodiversity), it seemed like a good opportunity to post some slide scans, accompanied by a few words written for an article published in the Summer 1996 edition of Wildlife Australia.

The Simpson Desert. To some the name may conjure images of lifeless sand dunes, of a stark and deadly landscape. To visiting naturalists, the Simpson is a place of subtlety, surprises, life, colour and great contrasts.

The Simpson Desert covers part of three states at the arid centre of Australia. More than 1,000 parallel sand ridges, often running unbroken for great distances, form a unique landscape. It is one of the world’s great sandy deserts.

Lobed Spinifex (Triodia basedowii) forms hummocks on dune crests. It provides refuge for many species of desert fauna.

Central Military Dragon (Ctenophorus isolepis).

Aboriginal people lived in this desert for countless generations, basing their lives around wells and an intimate contact with the desert plants and animals. Early Europeans saw it as a dead zone — devoid of flora and fauna of any real value.

The Desert Grevillea (Grevillea juncifolia) is one of the many desert plants that can survive long periods without rain. I watched Black Honeyeaters coming over the sand ridges to land in them for a brief nectar refuel.

These notions faded as expeditions and surveys revealed an astonishing biodiversity. Far from being a monotonous and lifeless wasteland, the Simpson Desert encompasses a variety of constantly changing land-forms, each providing habitat for many superbly adapted plants and animals. New and exciting biological discoveries are continually being made.

To the visiting photographer, the Simpson is overwhelming. The vast, silent landscapes do not easily reveal their secrets. In a dry creek bed between sand ridges, we share the midday shade with a host of birds.

The dry bed of Gnallan-a-gea Creek, Simpson Desert.

The change from afternoon into night is soft and magical. As the sun sinks, the red sand on the ridges glows with a luminous intensity. The shadows of the wildflowers and other plants lengthen.

Silence returns and cloaks everything with a palpable intensity, The dome of the sky sweeps down to invade the ground as the twilight colours fade and the horizon vanishes, Another day in this remarkable place has ended.

Gillens Moniter (Varanus gilleni), a species of small goanna. We found wandering about the creek bed at night.

And who ended up on the cover of that book? A character I’d been hoping to meet.

LINKS:

Tigers on the move

There’s always something to discover in a Queensland backyard if you’re into natural history, even if it’s a fairly ordinary one like ours.

Returning from an early Saturday morning walk, the dog and I were stopped in our tracks. Our flowering Ivory Curl Flower tree (Buckinghamia celsissima) was alive with a swirling mass of Blue Tiger butterflies.

With the recent rain and heat our desert-like yard evolved into a weedy suburban Amazon, and with the green came the insects. Lots of them. Bladder Cicadas deafened all at twilight, Garden Orb-weaver spiders made each trip to the bin at night an arm-waving obstacle course and Scarlet Percher dragonflies buzzed us in our dodgy inflatable pool.

Blue Tiger butterflies swirl about our Ivory Curl flower tree, a magical Saturday morning coincidence of flowers and migrating butterflies. Text and all photographs by Robert Ashdown. Click on an image for a larger version.

However, this swirling mass of butterflies was something else. Standing under the tree, I could see a stream of the fluttering insects doggedly heading toward our house from the south-west. As they neared the Ivory Curl Flower they’d drop immediately, landing and seeking nectar, oblivious to observers. Native stingless bees buzzed about dodging the butterflies as well as the tiny flower spiders seeking to capture a meal. A microcosm of insect activity centred on this one magnetic tree.

Blue tiger butterflies feed on certain plants to obtain pyrrolizidine alkaloids, chemicals that make them quite unpleasant to animals trying to eat them. They have also been observed drinking from moist sand in the dry season.

The Blue Tiger (Tirumala hamata) is one of the butterfly species that sometimes moves in enormous numbers across southern Queensland — others include the Caper White (Belenois java) and the Lemon Migrant (Catopsilia Pomona). The Blue Tiger is a member of the Danais group which includes many migratory butterflies, the most well-known of which is the Monarch. The Monarch undertakes huge regular migrations in America and even managed an overseas trip, arriving in Australia in the 1870s, possibly blown this way by cyclones or travelling as larvae stowed away on plants that subsequently became weed species here. Once established in Australia, the Monarch settled down to a more sedentary life, only undertaking less-ambitious journeys from inland areas to the coast as the temperature drops with winter.

Blue Tigers are also found in the Philippines, Indonesia, Solomon Islands, Fiji, Tonga and Samoa, In Australia, they breed in monsoon forest (vine thicket) and littoral rainforest in south-east Queensland, or around Darwin in the wet season when larval food plants produce new growth.

Blue Tiger butterflies can be hard to spot during winter but large numbers can still sometimes be found. Winter is a tough time for butterflies as host plants are unable to offer fresh foliage for larvae to feed on and fewer nectar sources are available. Some Australian species, such as the Blue Tiger, have a survival strategy: they gather in large numbers and put their lives on hold for the winter. This dormancy, or ‘aestivation’ (also known as ‘overwintering’) buys adult butterflies time. In summer an adult may only live for one to two months; however, a butterfly that has overwintered can live as long as nine months. Those few extra months may mean that winter butterflies can make it through to the spring, a much more favourable breeding time. Blue Tigers have been found overwintering in vine forest in sandy gullies and creek banks, resting on branches or twigs close to the ground.

Invalid Displayed Gallery

[CLICK ON IMAGES ABOVE FOR LARGER VIEW]

In spring and summer, they take to the air, often in huge numbers. Some claim that we are currently experiencing the highest number of butterflies seen in south-east Queensland for 40 years. When interviewed by the ABC, Queensland Museum curator Dr Christine Lambkin explained that the numbers were due to a combination of rain and heat providing perfect breeding conditions for these insects.

“We have had a long extended dry period that has been broken by good rains at the right time of the year,” she said. “So we have got the warmth as well as the rain and that is what has caused the adults to break the aestivation, which is the insect hibernation, and emerge in numbers. Some of them will be trying to mate and lay eggs so that the caterpillars are going to come up on that flush new growth (of butterfly food plants) from the rain.”

With numerous pale blue streaks and elongate spots, the blue tiger is an attractive insect. The pupa of this butterfly is a shiny green with gold spots that turn silver. The caterpillars are grey with black bands, orange lines and long filaments. They feed on vines found in dry rainforest scrub.

Are the Blue Tigers heading anywhere in particular? According to old mate Google, the online consensus appears to be that this species heads south from northern Queensland in spring and summer, moving through Brisbane (where they are normally not often seen) in large numbers. They have been recorded reaching as far south as Victoria. However, other observers have recorded them heading north, as seen at our place this year.

Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service ranger Rod Hobson recounts watching huge numbers of blue tigers “ … flying north into the never-never of blue off the end of Sandy Cape at Fraser Island to perish at sea. I used to find large numbers of dead blue tigers in the beach wrack for days after these events.” It’s hard to imagine what they were seeking in the Pacific Ocean, if they had a destination in mind.

Strangely, when seen flying about later in autumn, Blue Tigers appear to be moving in different directions. I asked entomologist Chris Lambkin if the butterflies were perhaps being blown in one direction by prevailing winds. Chris does not believe this is the case; she has seen them moving east into the wind.

While butterflies are perhaps the best-known group of insects, much remains to be known about their taxonomy and ecological requirements, important information if we wish to conserve them.

So it seems we don’t know why they head in one direction. Clearly, the movement of butterflies in Australia is not well understood. Some research has been done — Dr Courtenay Smithers at the Australian Museum initiated a tagging program for butterflies in the 1970s, which gave some idea of the seasonal movement of Monarchs in Australia and discovered some over-wintering sites for the species. However, not a great deal appears to have been discovered about butterfly travel plans in the decades since. Much of what has been written on butterfly movement has appeared in the newsletters of ever-active organisations such as the Butterflies and Other Invertebrates Club and Land for Wildlife (see, for example, this article on Caper White migration).

Dr Lambkin believes there just isn’t enough scientifically recorded information about these butterfly mass movement events to allow for the full picture. Why the Blue Tigers are all heading in one direction must, for the time-being, remain another of those wonderful mysteries of nature — to be watched and enjoyed.

Links

Ogre on the fence

How could you not like a spider with a name like Ogre-faced? I found this ogre, more commonly known as the Net-casting Spider (Deinopis subrufa), lurking on a fence facing a busy suburban street.

This is a female net-casting spider. Males are much thinner. The Queensland Museum reports that “At night, the female spider builds a brilliant blue-filled rectangle of silk which it swirls around passing prey with remarkable speed.”

‘In a bygone but more erudite society this spider was called the Retiarius (lit. “net-man” or “net-fighter” in Latin) after the lightly clad gladiator of ancient Rome who faced his more heavily encumbered opponent armed only with a cast net and trident.’ Rod Hobson

The Australian Museum tells us more about its net-casting abilities. “In order to have an aiming point, the spider often drops splashes of white faecal droppings onto the leaf or bark substrate over which it is poised. When an insect walks across this ‘target’, the spider plunges its net downward to envelop and entangle it. If successful, the spider silk-wraps the prey item, bites and paralyses it, and then feeds on it. Net strikes will also be made at flying insects that stray too close. An unused net is sometimes stored by hanging it on nearby leaves for the next night’s hunting, or the spider may eat it.”

Mystery of the clicks

The sounds of nature are always there, even in the city and suburbs, if you stop to hear.

Sometimes they are memorable, melodic noises. I remember lying in bed as a child in Brisbane in the dead of night listening to the cheerful call of a Willy Wagtail or the haunting, ‘mo-poke’ call of the Southern Boobook Owl. At other times the sounds are mysterious drones, clicks or whistles, all just part of the background of summer in the suburbs. Unless it’s a click that you’ve been trying to find the owner of for years.

In our street on dusk after the first hot summer day, an all-enveloping, loud, continuous guttural rumbling fills the air. This is the call of the large, green Bladder Cicada (Cystosoma saundersii). These beautiful, large green insects are hard to find, given how loud and large they are.

Catching cicadas is a childhood pastime during an Australian summer. Some species sit warily high up on tall gum trees, taking flight at the slightest movement. Others, such as this Bladder Cicada, call on twilight and are well camouflaged. If detected, these cicadas will suddenly drop to the ground, hoping to avoid being caught.

Bladder Cicadas are found in closed forest and gardens on coastal Queensland and New South Wales. In males, the large, hollow abdomen acts as a resonant sound radiator, allowing the cicada’s song to carry long distances. In our suburb, the call of these insects on a summer evening can be deafening.

Most of the life of this cicada, like most species of this insect, is spent below ground as a nymph, feeding on the sap from the roots of trees. On warm summer nights, nymphs leave the safe, dark earth, climb a tree or fence post and the adult cicada emerges from its brown skin, unfolding delicate wings that are pumped full of fluid as they unroll and harden. The shed skins, or ‘nymphal exuviae’ remain behind, clinging motionless and empty to a fence post, evidence of the adult cicada’s arrival above ground in the night.

The adult cicada usually only lives for two to three weeks. Males call to attract females, who fly to the male chorus and land within 50 cm of the male.The female produces a pheromone which is distributed by wing-clicking. The male responds by changing to the courtship song, before moving towards the female and mating. The female cicadas lay eggs in the live branches of plants that are suitable for the larvae, which hatch and climb down below ground.

For many years, I’ve pondered a strange, intermittent clicking noise heard in summer in the suburbs of Brisbane and here in Toowoomba. The clicking was recently described by a naturalist mate, who had also heard them, as ‘like the sound made by two Aboriginal message or song sticks clacked together’. A perfect description. Advice from those who study insects and like stuff has pointed me towards another green cicada as the likely suspect — the Bottle Cicada (Glaucopsaltria viridis). This cicada has a long, whistling sound on dusk, but is known to produce some intermittent clicking sounds during the day.

Bottle Cicadas are about 3 cm long. The male has an inflated hollow abdomen. They are found in south-eastern Queensland and northern New South Wales. Their main song is a continuous, monotonous whistle at dusk, between October and April.

It’s taken years, but I finally found one of these insects. While walking on dusk past a hedge from which I’d previously heard the mysterious clicking, I noticed a long whistling call emerging from all over the hedge. Closing in on one source of the sound, an insect flew down to the ground, where my faithful fellow-naturalist dog tried to eat it. I wrestled the insect from the dog’s mouth, and found that it was indeed one of these green cicadas. I had at last solved my personal mystery of the weird clicking sounds.

Bottle Cicada. Cicadas have two obvious, large, compound eyes, and three ocelli. Ocelli are jewel-like eyes situated between the two main, compound eyes. It is thought that ocelli are used to detect levels of light and darkness.

Some naturalists are dedicated to investigating, and recording and analysing, the sounds of nature. Sid Curtis describes on the Nature Recordists forum his investigation into the clicking call of Bottle Cicadas, using some specialist microphone and and recording gear:

Here in Brisbane the Bottle Cicada is common in our suburban gardens. Like many cicadas, the males all sing at the same time, thus making it difficult to locate any one individual. With just one’s ears, that is. Klas’s so excellent and highly directional Telinga mic and reflector make it easy. They sing at dusk: “Continuous and without apparent variation”, is how Dr Max Moulds author of the book Australian Cicadas, describes it. But that is not all.

During the day they have a very different and far-from-obvious call. Just a few (up to 5) short sharp ‘bips’ over a second or so. Then silence for several minutes. Also very effective in making it difficult to locate the insect by the sound. (And incidentally, using Peak LE software and a Mac computer, I have strung these bips together without spaces between them, and produced their continuous dusk song.)

To locate one during the day, play a recording of the continuous dusk song, and the cicada just has to join in. He won’t keep going for long after you stop the recording, but you can start him again. The dusk song of course is to attract females for mating. The song changes if a female arrives. I surmise that the intermittent day song is aimed at males — to enable each to maintain his personal space. I hoped to test this by concealing a small speaker fairly close to a male and playing a recording of the spaced-out day song. Unfortunately my garden is very small; I’d have to use the garden next door. This was a possibility but the house was sold and the new owners cleared the whole area — all trees and shrubs have gone, and there’ll be no cicadas.

But back to mechanical noise. At one stage someone used a motor-mower with

a whine of just the right pitch to match the cicadas dusk song. And they

joined in!

Now, I’ll need another mystery of the natural world to solve. Luckily, there are zillions more out there!

Links:

- Queensland Museum information sheets on Australian cicadas.

- A tricky question about cicadas.

- Inside the life-cycle of Australian cicadas.

Also see my earlier post on cicadas here.

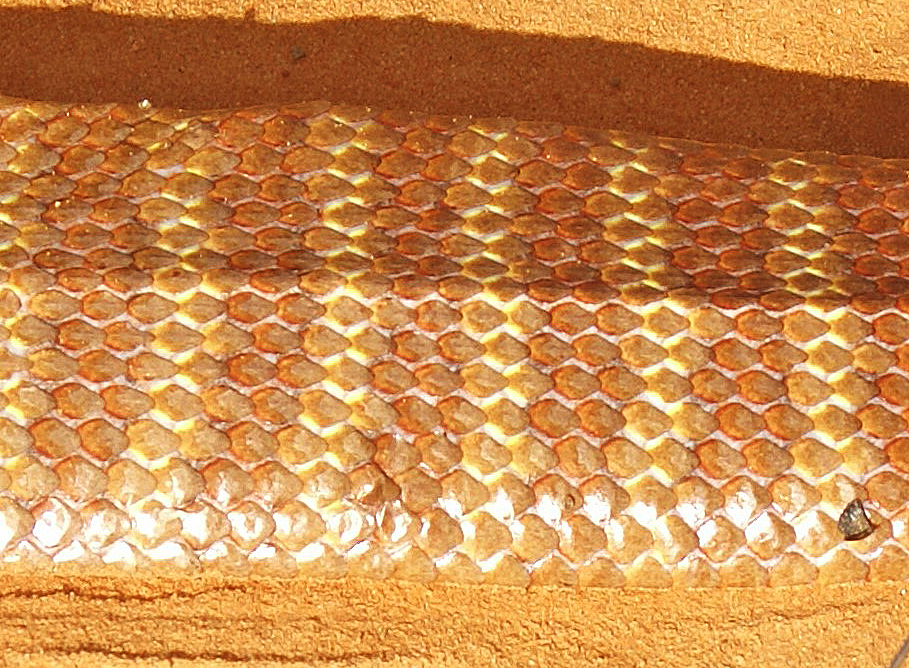

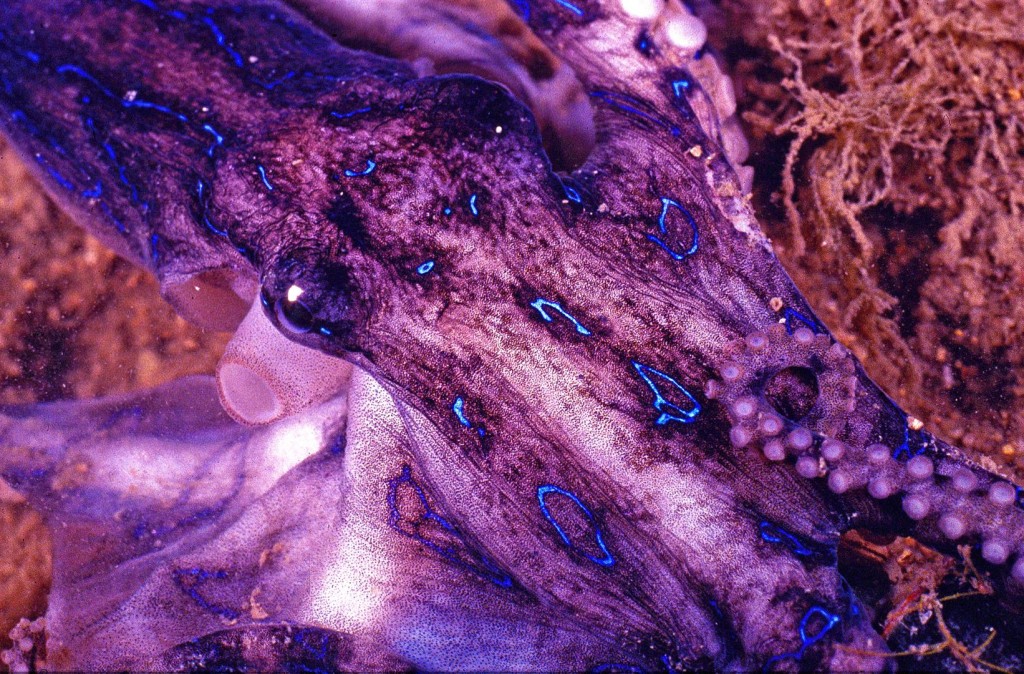

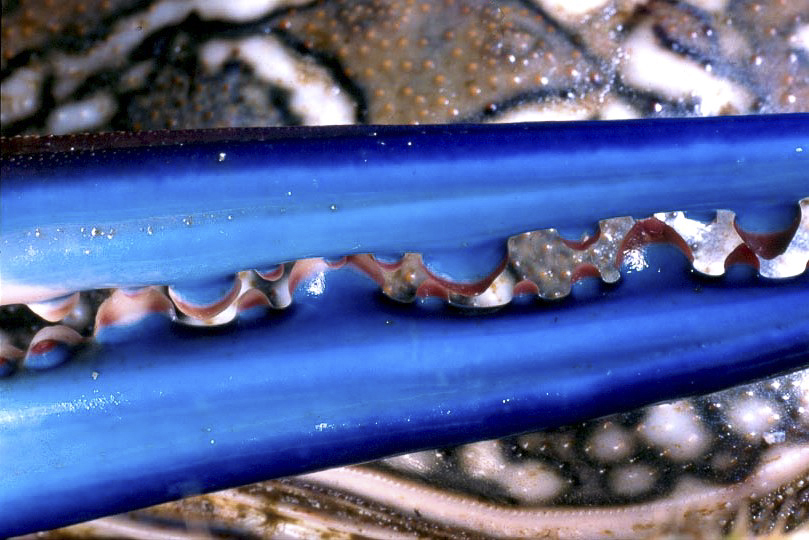

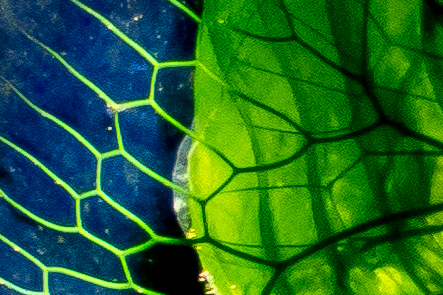

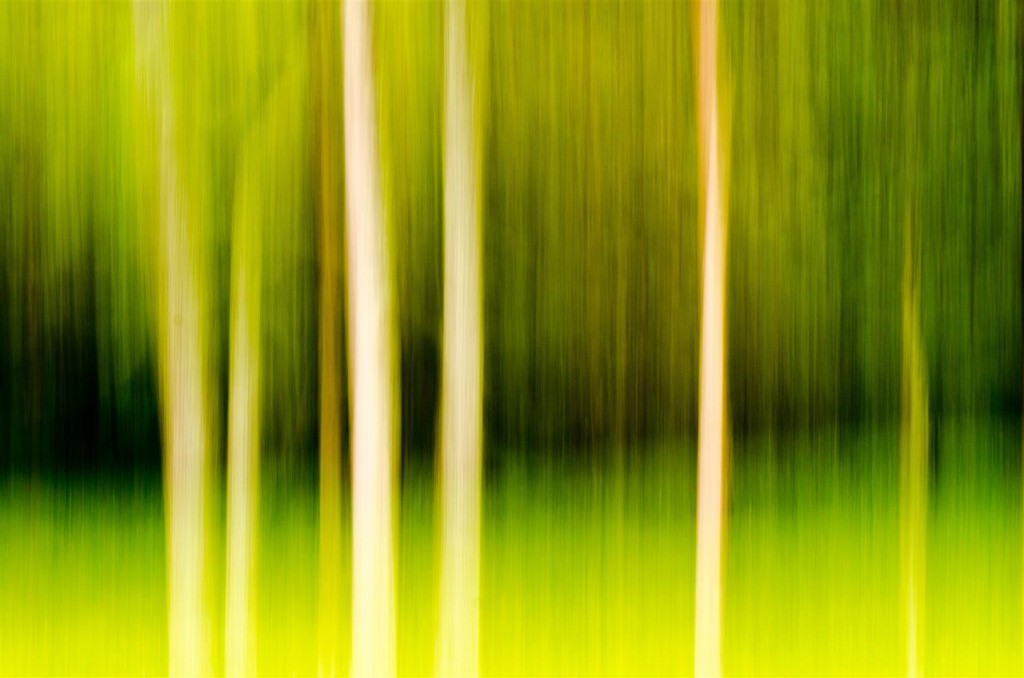

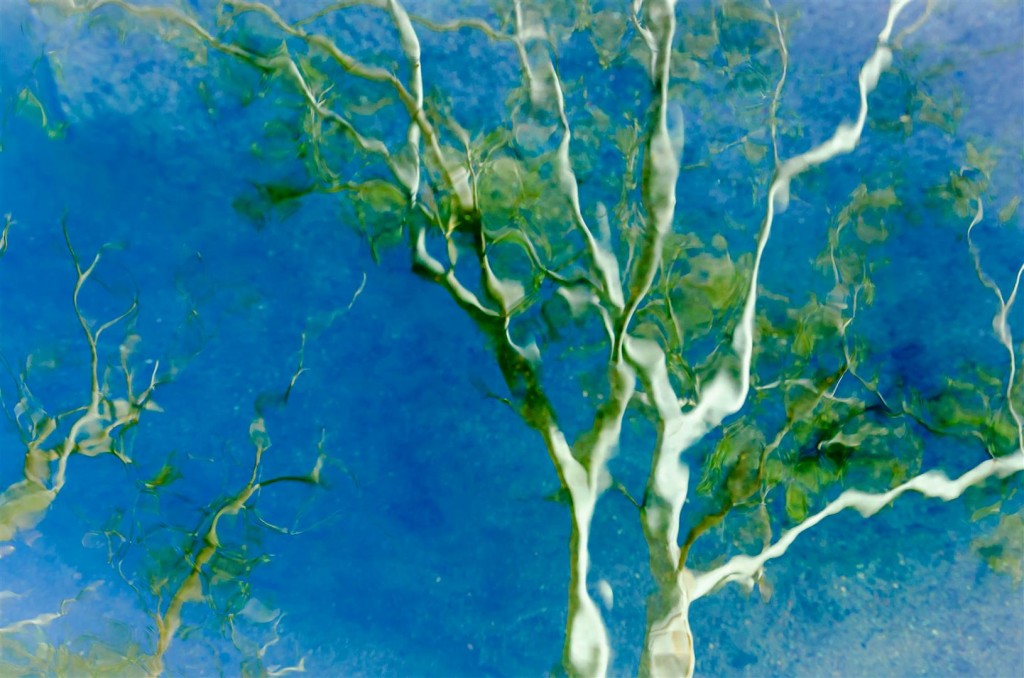

Blue, red and green

Three images from guest photographer Brett Roberts.

Brett, a colleague in the Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service, is a photographer who combines a technical mastery of the camera with an eye for arresting composition and abstract expression. Here are three sublime glimpses of the shimmering, ever-shifting patterns and colours of nature.

‘To take photographs is to hold one’s breath when all faculties converge to capture fleeting reality. It’s at that precise moment that mastering an image becomes a great physical and intellectual joy.’ Henri Cartier-Bresson, The Mind’s Eye: Writings on Photography and Photographers

‘Mysteries lie all around us, even in the most familiar things, waiting only to be perceived.’ Wynn Bullock

Cryptic dragon

A Southern Angle-headed Dragon (Hipsilures spinipes), photographed at the Goomburra section of Main Range National Park.

The Southern Angle-headed Dragon is found in sub-tropical rainforests in south-eastern Queensland north to the Gympie area and in northern New South Wales. This small, well-camouflaged reptile likes to perch on the trunks of trees where light penetrates to the forest floor, such as at edges of creeks and tracks. Southern Angle-headed Dragons eat insects and arthropods, such as centipedes and spiders. In December, females lay up to seven eggs in shallow nests in clearings, and there is evidence of communal nesting. Photo R. Ashdown.

A name for an earless dragon

It’s taken a while, but a tiny endangered Darling Downs reptile has finally been given a scientific name.

The newly-named Condamine Earless Dragon (Tympanocryptis condaminensis). Earless dragons are found throughout most of mainland Australia. They live in dry open areas such as featureless stony deserts, cracking clay plains and grasslands. Most extend across vast tracts of the interior, but one southern temperate grassland species reaches the Darling Downs. Photo R. Ashdown.

A paper published recently by the Museum of Victoria has assigned scientific names to three species to the genus Tympanocryptis, commonly known as ‘earless dragons’.

The paper The Role of Integrative Taxonomy in the Conservation of Cryptic Species: The Taxonomic Status of Endangered Earless Dragons in the Grasslands of Queensland presents the results of taxonomic research from a team headed by Dr Jane Melville from Museum Victoria, and which included Katie Smith and Sumitha Hunjan (Museum Victoria), Luke Shoo (The University of Queensland) and Rod Hobson (Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service).

The paper provides clarification of the taxonomy of what has been a confusing genus of reptiles. Some of the earless dragon species still await description, while others may be part of a species group. Naming species is usually never straight-forward.

A Condamine Earless Dragon (Tympanocryptis condaminensis). Tympanocryptis means ‘hidden ear’ — the ears of these dragons are covered by scales that make them appear earless. Photo R. Ashdown.

The taxonomic status of the earless dragon known from the Darling Downs area has long been uncertain, so the description of this species as Tympanocyptis condaminensis (with the common name Condamine Earless Dragon) has been welcomed by herpetologists, naturalists, and the Darling Downs community that has taken this little reptile to heart.

There has been a bit of history leading to this point, as described in the paper:

The grassland earless dragons of south-eastern Queensland have long been of conservation concern. Originally the earless dragons from the Condamine catchment, in the eastern Darling Downs, were identified as Tympanocryptis pinguicolla, after being first discovered in the region over 30 years ago.

However, subsequent surveys failed to detect these dragons and they were believed to be locally extinct until their rediscovery in 2001 when a specimen was found in a grass verge along the margin of a fallow paddock. It was found that these earless dragons were restricted to mixed cropping land (maize, cotton, sorghum, sunflower etc.), remnant native grasslands and grassy verges along roads. Based on these data, the T. pinguicolla populations from the Darling Downs were listed as an endangered species of high priority in Queensland. Since then the taxonomic designation of these populations has been changed to T. cf tetraporophora, based on phylogenetic and morphological data.

The paper describes three new species of earless dragon, all found in grassland areas of Queensland, now highly impacted by human activity such as agricultural and pastoral industries, and mining and gas extraction.

The Five-lined Earless Dragon (Tympanocrytptis pentalineata). Currently only known from the one location, 50 km south-west of Normanton in the gulf region of far northern Queensland. Named for the dorsal colour pattern of the new species, characterised by five longitudinal white stripes extending along the body.

The Roma Earless Dragon (Tympanocryptis wilsoni). Currently known to occur in grasslands, dominated by Mitchell grasses, on sloping terrains in near the town of Roma. Named in recognition of the contributions of Steve Wilson to Australian herpetology, in particular his direct contribution to the understanding of Tympanocryptis diversity in Queensland. Steve Wilson discovered this new species during a survey, provided photographs in-life and collected the only voucher specimens.

The Condamine Earless Dragon (Tympanocyptis condaminensis). Occurs in the remnant native grasslands, croplands and roadside verges of the eastern Darling Downs, on black cracking clays of the Condamine River floodplain. Found as far north as the Pirrinuan/Jimbour area, west as far as the town of Dalby and south to the township of Clifton. To the east it has been recorded to the eastern extremity of the Darling Downs in the Aubigny/Purrawunda area on the western outskirts of Toowoomba. Specific locations include: Oakey, Mt Tyson, Brookstead, Bongeen, and Bowenville. Named for the Condamine River and its floodplain on which this species occurs.

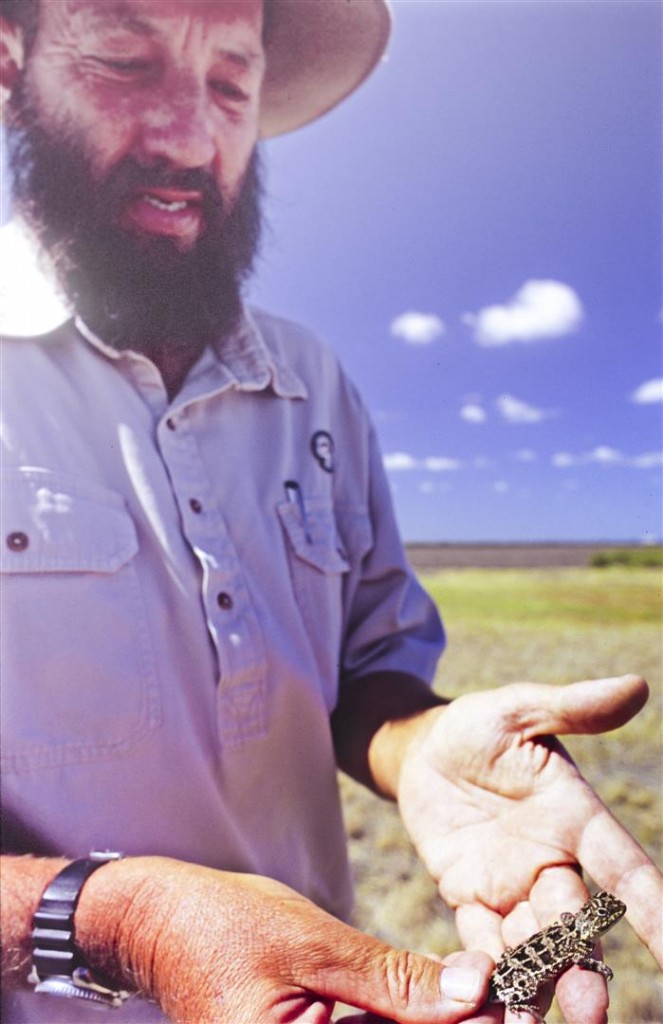

Steve Wilson gets up close to a Condamine Earless Dragon at Kunari, Darling Downs, 2006. Photo by R. Ashdown.

Two characters I’m happy to call mates have been heavily involved in this dragon discovery work. Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service colleague Rod Hobson was one of the authors of the paper, while one of the newly-described dragons, the Roma Earless Dragon (Tympanocryptis wilsoni), was named after photographer Steve Wilson. I have accompanied both Steve and Rod on some memorable expeditions looking for, and photographing, the Condamine Earless Dragon in cropland and roadside grasslands to the west of Toowoomba.

The Darling Downs community has long campaigned for the conservation of the tiny dragon found in their area. The Pittsworth District Landcare Association and the Mt Tyson District Landcare Group were both instrumental in initiating and resourcing the research which has resulted in this taxonomic work. Local landowners the Wooldridges (Bongeen) and the Halfords (Mt. Tyson) took a keen interest in the future of the dragons found on their properties and in their local area.

An adult Condamine Earless Dragon caught on Kunari by Rod Hobson, a Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service (QPWS) ranger. QPWS staff have been involved in research and conservation of the species since its rediscovery. Photo R. Ashdown.

So where to now for these newly-named reptiles? The authors believe that the conservation status and management of this group of dragons in Queensland needs to be investigated further.

From the paper:

Earless dragons are currently known from only a few sites within the Darling Downs region and are restricted to what were previously native grasslands. The Darling Downs is an important agricultural area on the western slopes of the Great Dividing Range in southern Queensland.

Prior to European settlement, it was an area characterized by open prairie-like grasslands grading into Brigalow (Acacia harpophylla) and Belah (Casuarina cristata) on cracking clay soils. These fertile soils have been heavily modified since European settlement and very little native grassland remains, making this one of the most threatened ecosystems in Queensland.

“The grasslands around the Darling Downs are subject to both mining (coal seam gas exploration) and land clearing encroachments. That loss of habitat is pushing the dragons into smaller and smaller areas — we found some along roadside verges, trapped on that very narrow strip of land,” says Jane Melville, Senior Curator of Terrestrial Vertebrates at Museum Victoria, and lead author of the paper.

Melville believes the discovery of an additional species on the Darling Downs highlights how little is known about fauna in these grasslands and the fundamental need for further ecological and genetic research on both species.

“We need to establish broad baseline data, which can be used to develop conservation management strategies,” she said. “There is a real risk of these species becoming extinct before we know anything about them.”

The Grassland Earless Dragon

An article written by Rod Hobson for the Winter 2006 edition of the Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service publication The Bush Telegraph gives an overview of the history of the Condamine Earless Dragon.

In the early 1970s amateur herpetologist Terry Adams found two little lizards in the black soil country at Mount Tyson on the eastern Darling Downs. These lizards caused a few raised eyebrows when they eventually came to the notice of staff from the Queensland Museum. Here was a new species for Queensland — a lizard that until then was only known from small and isolated populations confined to native grasslands west of Melbourne, the ACT and adjoining areas of New South Wales.

It was the grassland earless dragon Tympanocryptis pinguicolla, regarded as one of Australia’s most rare and threatened of species. Repeated searches after Terry’s initial discovery however failed to reveal any more individuals of this little dragon lizard. It was feared to be extinct in Queensland.

Then, in January 2001, students from the University of Queensland’s Gatton campus caught a small lizard whilst working on a project on the property of Dennis and Rose Wooldridge, at Bongeen on the eastern Darling Downs. The students’ supervisor Dr. Luke Leung forwarded the lizard to the Queensland Museum for identification. Its arrival there caused a furore — here was the lizard thought to have become extinct in Queensland since its initial discovery in the early 1970s. It was at this early stage that Queensland Parks and Wildlife’s Toowoomba office became heavily engaged in the Grassland Earless Dragon Project, a commitment that continues to this day.

Dennis Wooldridge stands in a crop of cotton on his property Kunari at Bongeen on the Darling Downs. The Condamine Earless Dragon is quite at home in a mixed cropping regime of cotton, sorghum, sunflower and maize. The dragon also requires adjoining remnant grasslands for breeding and as a retreat during harvesting operations. Photo R. Ashdown.

Discussing the dragon at Kunari. (L to R) Dennis Wooldridge, Alison Goodland, Rod Hobson and Rose Wooldridge. Kunari was the original site of the dragon’s rediscovery. Dennis and Rose have continued to be enthusiastic and committed participants in the grassland earless dragon project. Alison at the time worked for the Queensland Murray-Darling Committee and was instrumental in the grassland earless dragon project since its inception. Photo R. Ashdown.

Since those heady days quite a few organisations, both government and non-government, have become involved with this great little lizard. Steve Wilson, Patrick Couper and Andrew Amey from the Queensland Museum have been ready and willing to provide technical and scientific information as needs arose. Students and staff from the University of Queensland’s Gatton campus have been busy on research projects, especially on the genetics of the species.

Tom Halford releases a clay dragon into the ‘biodiversity area’ at Mount Tyson State School during the ‘Kids and Dragons’ project. Coordinated by the Mount Tyson District Landcare Group and funded by a community awareness grant from The Department of Natural Resources, Mines and Energy, the project raised dragon awareness in the local community. Tom’s parents, Paula and Peter Halford of Nyleta at Mount Tyson, have been enthusiastic in coordinating dragon conservation efforts on the Darling Downs since they discovered dragons on their property several years ago. Photo Alison Goodland.

Carly Starr, a student from University of Queensland (Gatton Campus) applies fluorescent powder to track an earless dragon during her Masters project on the species. This picture was taken in sorghum stubble on Nyleta, a property owned by dragon enthusiasts Paula and Peter Halford at Mount Tyson on the Darling Downs. No animals were harmed during the study. Photo Josh Bassett.

Condamine Earless Dragons can at times be seen perched on grass as they survey their surroundings. Photo R. Ashdown.

Students Leigh Jewell, Violeta Toneva, Carly Starr and Stephanie Goebel under the tutelage of Drs. Greg Baxter and Luke Leung have contributed significantly to our understanding of the species through their tireless fieldwork.

Alison Goodland, initially through her work for World Wildlife Fund, and lately with the Queensland Murray-Darling Committee/Condamine Alliance, has been in ‘boots and all’ since the early days of the project. The Mount Tyson Landcare Group has contributed generously towards the project with their time and enthusiasm, especially through local landowners Paula and Peter Halford.

Heather Hanlon (proprietor of speciality chocolate shop and restaurant White Mischief) and Paula Halford (Mount Tyson District Landcare) inspect a newly hatched chocolate earless dragon. Carefully hand-crafted by Heather, these novelty lizards have sold well, with funds raised going directly to dragon conservation. Photo R. Ashdown.

Heather Hanlon of White Mischief chocolate shop and restaurant at Mount Tyson has been industriously turning out chocolate earless dragons — with all funds going towards earless dragon research and conservation initiatives.Shona Clark-Dickson and her pupils from Inglewood State School raised just under $200 for the dragon through sales of chocolates and greeting cards at their school fete — well done to Shona and the kids.

Throughout the entirety of the project Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service (QPWS) staff from the Toowoomba office have been involved in giving school talks, media interviews and writing articles on this great little Aussie battler of a lizard, which chooses to make its home amongst the sorghum, cotton and sunflower crops of the eastern Darling Downs.

Pupils of Inglewood State School with their teacher Shona Clark-Dickson. The class raised $200 for dragon conservation by selling greeting cards and dragon chocolates at their school fete. Photo R. Ashdown.

To date we have records from as far north as Jimbour, west to Cecil Plains, south to Nobby/Clifton and east to Mount Tyson and all thanks to the local landowners who have generously allowed us access to their lands.

We couldn’t have had the successes that we’ve had to date without your unstinting enthusiasm and kindness. This happy marriage of such a diversity of groups couldn’t have succeeded to the extent that it has without you. So thanks to everyone involved and may the marriage be a long and happy one.

Links:

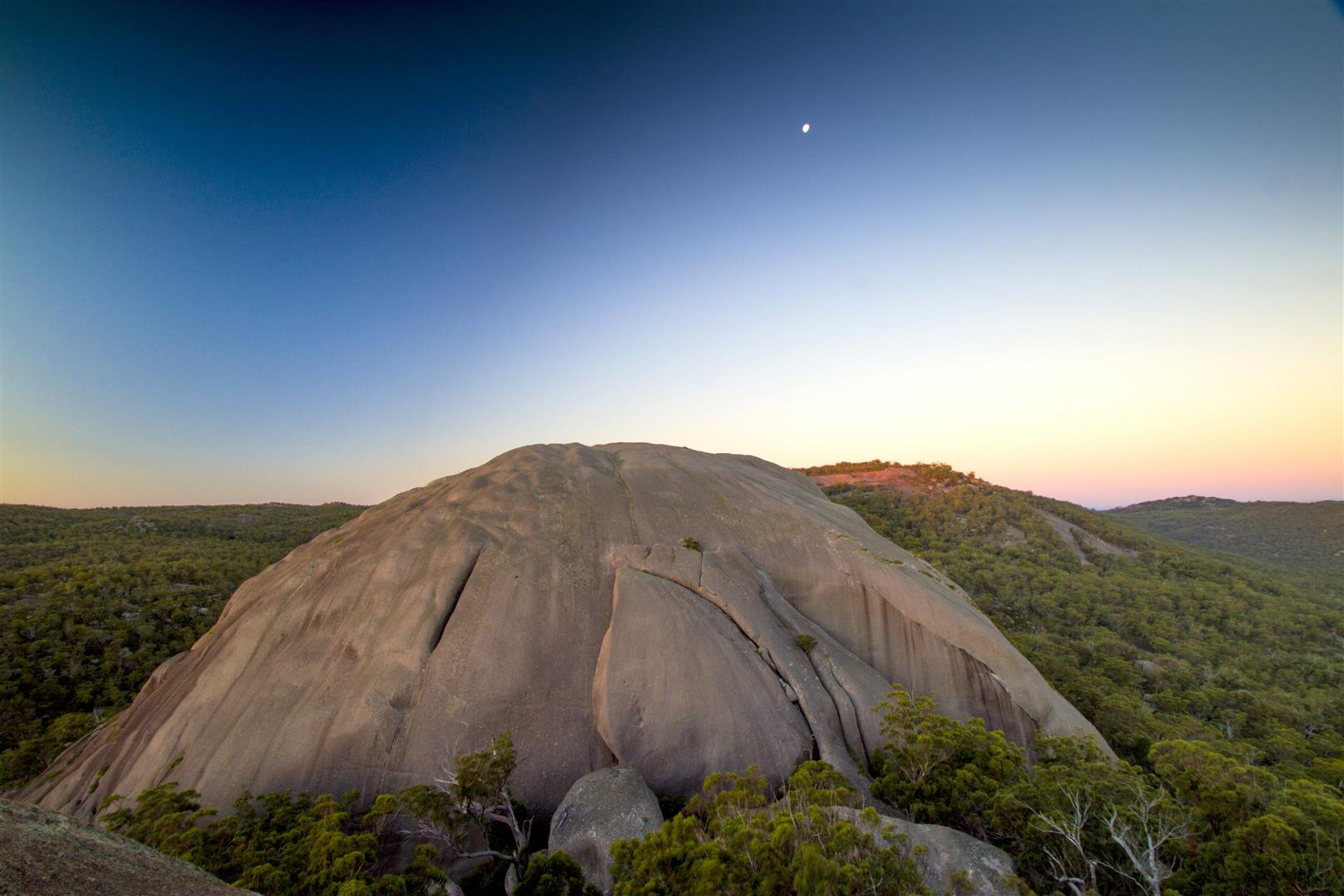

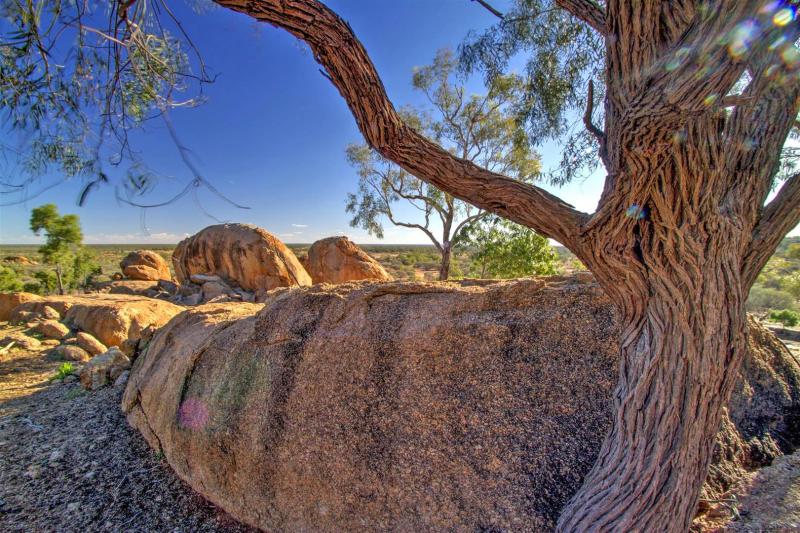

Girraween granite

Girraween National Park, about 260km south-west of Brisbane, is a majestic place of granite wildness.

Girraween has grown on me steadily over the decades I’ve been visiting. I have many memories of time spent in this place, with friends, family, work colleagues or alone. Something new is revealed each time I visit. For a photographer artist, naturalist or walker it’s an ongoing revelation — a place where you can lose yourself in nature at it’s most dramatic. It’s always an inspiration for me.

I only made it there twice in 2014, but both trips were enjoyable.

Can there be a more exhilarating walk anywhere? Rob Mancini on the rocky walk to the top of the Pyramid. Nov 2014.

Photographer Gary Cranitch works to capture the rapidly changing sunset light.

It’s noon, and 35C. Cicadas shriek and the granite reflects heat like a furnace. Another storms builds on the horizon.

A warm and active Water Skink (Eulamprus quoyii) checks out passing walkers. Photo by Harry Ashdown.

The sun sinks through rain in the west, while large storms build once more to the east.

Night slowly approaches again.

The summer heat is ideal breeding time for frogs. These are male Stony Creek Frogs (Litoria wilcoxii) in their finest yellow coats.

A Wyberba Leaf-tailed Gecko (Saltuarius wyberba) emerges from cracks in the granite to search of a meal.

This blog post is dedicated to the Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service rangers at Girraween, both past and present, who have worked so hard to preserve this place for future generations.

Links:

- Girraween National Park (everything you need to know!).

- Girraween National Park (QPWS site).

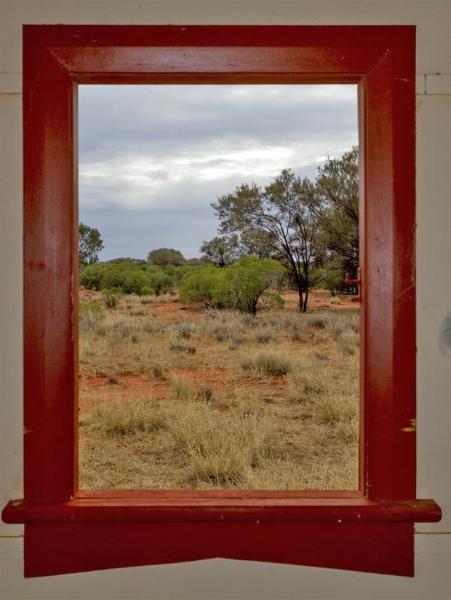

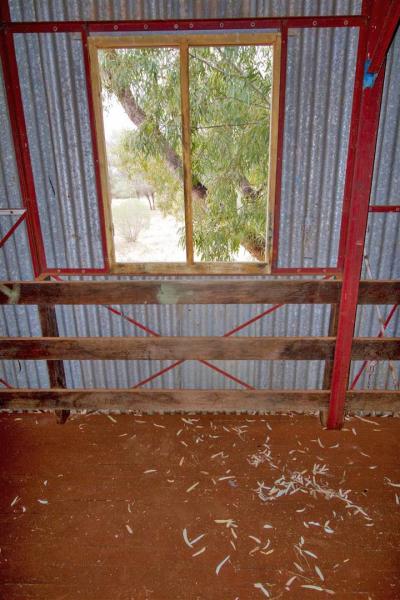

Currawinya National Park — red sand, granite and mulga

Some images from a recent work trip to one of my favourite places.

Click on a thumbnail for larger image.

The Palms — small in size, big in character

We tend to think of our national parks as large, wild places. And so they should remain. However, there are smaller parks, full of charm, that hold some great stories. The Palms National Park is one such place.

An enormous Moreton Bay Fig (Ficus macrophylla) began its life here at least 500 years ago as a seedling high up on another tree. As it grew, the fig’s long cable-like roots descended to the forest floor and gradually enclosed its host tree, restricting its sap flow. The fig’s large canopy also blocked out essential sunlight from the host tree, which slowly died. Today this immense fig dominates this section of the forest and provides habitat for a variety of animals. Photo R. Ashdown.

The Palms, near Cooyar to the north of Toowoomba, is small in size but big in character. Situated at the headwaters of the Brisbane River, The Palms conserves a small remnant of palm-filled subtropical rainforest and vine forest in a spring-fed gully. At just 73 hectares, this is one of the smallest national parks in Australia. However, it’s also home to one of the most diverse ranges of flora and fauna.

A spring-fed creek runs through the park, keeping Piccabeen Palms and giant rainforest trees alive. Photo R. Ashdown.

This is an area that has seen many changes. Indigenous Australian people camped and hunted in this area for thousands of years, and many may have also passed through on their way to the bunya nut festivals at the Bunya Mountains. Timber-getters arrived in the district to utilise the rich forests, and eventually much of the surrounding countryside was cleared. The forests were replaced with crops and grazing. So why does this patch of original scrub remain?

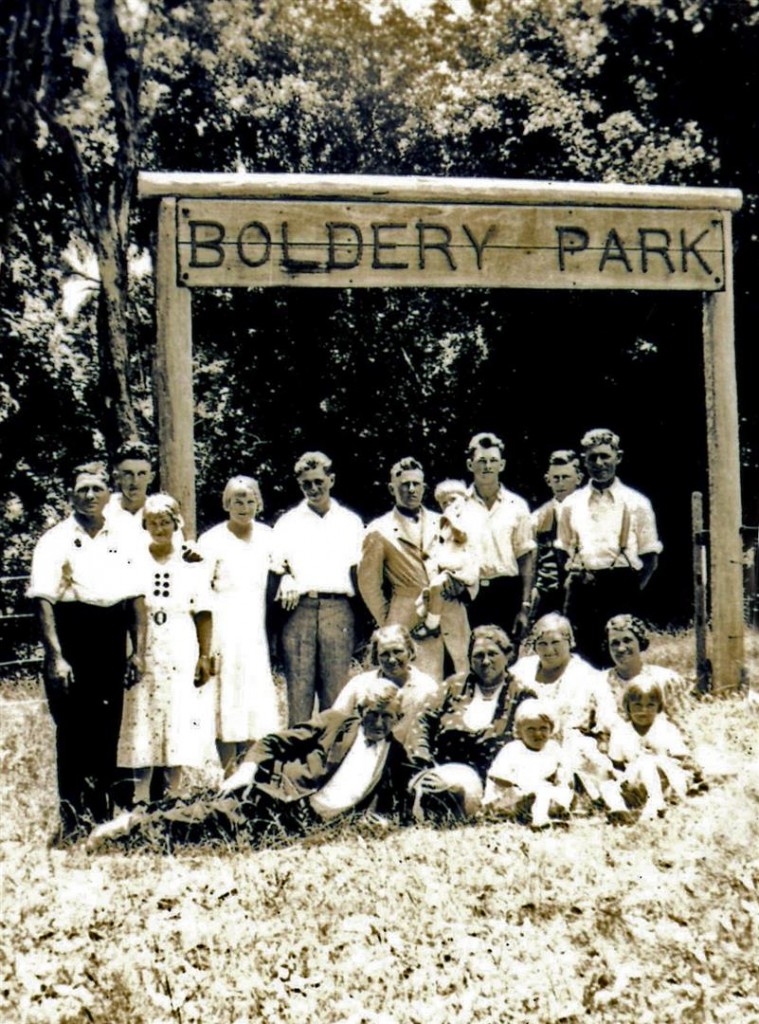

Enter Charles Henry Boldery. Born in Maryborough in 1890, Charles’ father and brothers owned properties and businesses in the Blackbutt, Yarraman and Cooyar districts. In 1921 Charles purchased a block of land consisting of 318.5 acres, about ten kilometres north-east of Cooyar. Charles lived on this land with his wife Emily (nee Christiansen) and their young children, and made a living by harvesting and selling the land’s timber.

Charles Boldery and his wife Emily (nee Christiansen) on their wedding day in 1915. Photo courtesy Boldery Family.

In 1927 Charles donated just over five acres of his property to the former Rosalie Shire Council. Charles wanted the site to be protected so that people would always be able to visit it and appreciate its natural beauty. This day-use area became known as Boldery Park, and the location became a popular spot for visitors. Charles lived in Brisbane from the 1960s onwards, where he eventually passed away in 1975.

In 2014, the Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service responded to a request by Charles Boldery’s grandson David Matthews to somehow formally recognise and remember the generosity and forward-thinking action of his grandfather. David assisted QPWS ranger Bryan Phillips-Petersen in creating some new interpretive signs for the park by providing historic photographs and information. The signs were launched this year by Member for Nanango Deb Frecklington. A bunch of Charles’ descendants were there to celebrate the park and to remember Charles.

Decendants of Charles Boldery, Member for Nanango Deb Frecklington and QPWS rangers gather at the park in August 2014. Photo R. Ashdown.

Fay Donald, 89, travelled from Brisbane with sister Shirley Green, 88, for the celebration; both women are the daughters of Charles Boldery. Photo R. Ashdown.

Every time I visit this small park I discover something new. After everyone had left the celebratory barbeque, I walked the track with some rangers. We froze to watch a Noisy Pitta, one of the most beautiful and elusive of rainforest birds, running down the middle of the walking track. I was reminded that even the smallest patch of Australian scrub can be a valuable refuge to our native plants and animals, as well as a place that rejuvenates and enthralls the visitor. I tip my hat to Charles while I’m there and nod a thankyou for his thoughtful act.

A gallery of images from The Palms (Click on a thumbnail for larger view).

All photos by Robert Ashdown.

Thanks to Bryan Phillips-Petersen, David Matthews and Lise Pedersen.

Link: The Palms National Park.