Some images from a work trip to Sydney late in 2011.

Author Archives: Robert Ashdown

Blue Ant

A female Blue Ant (Diamma bicolor), photographed by Rob Mancini at Porcupine Ridge in Victoria.

Blue Ants are actually a type of flower wasp, and only the females are flightless — the male looks more like a typical wasp with wings (it is smaller, slimmer and black with white spots on the abdomen). Many species of flower wasp have wingless females. Mating with such species occurs on the wing, with the male carrying the female wasp.

Female Blue Ants run along the ground in a jerky motion with head raised, searching for ground-dwelling insects such as beetle larvae and mole crickets. They paralyse the insect with a sting before laying eggs on it. On hatching, the wasp larvae eat the insect.

Adults of both sexes feed on nectar. They are found in Tasmania and south-eastern mainland Australia. Thanks to Rod Hobson for the ID.

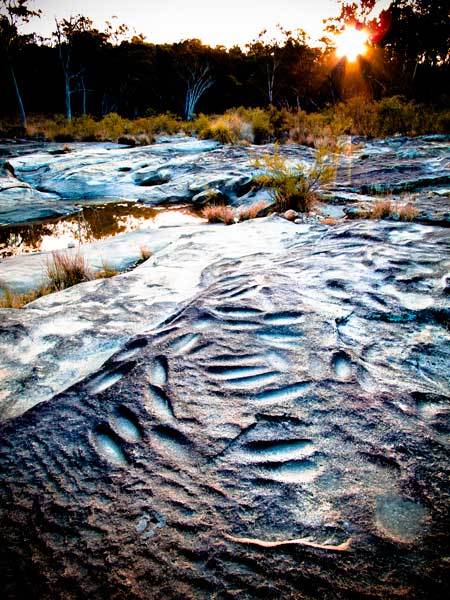

Sandstone country

Nesting Spotted Harriers

Spotted Harriers (Circus assimilis) are one of my favourite birds. I rarely get to see them but when I do it’s always a thrill. Often it’s while driving through the Darling Downs, usually when it’s almost impossible to pull over, a glimpse of a large, colourful raptor, sailing low and slow over a field, wings swept up, hoping to flush out small birds from below to dive on.

Adult spotted Harrier in flight. These raptors are solitary and nomadic and their numbers increase rapidly with booms in their prey — usually small mammals, ground-dwelling birds, reptiles or insects. They find temporary mates and their courtship display sees them fly to a great height before descending in slow spirals and side-slips, occasionally plummeting with half-closed wings. Photo copyright Paula Halford.

Having these birds nest on your patch must be exciting for a wildlife fan. Paula Halford, from the Mount Tyson area on the Darling Downs, has had that pleasure. She’s sent some great images and notes, and generously given me permission to share them.

Paula:

The parents nested in some mistletoe at the top of an ancient Mountain Coolibah about 50 metres from our house, so we have been watching them for the last three or four months. They are right next to a ripening barley field where the parents mostly hunt however they go much further afield down on the paddocks of wheat and barley.

Juvenile harriers on the nest. These birds breed between July and October, laying two to four eggs. Males help incubate the eggs, while the female assists him with hunting. Although most of the clutch is usually reared, there is a definite pecking order among chicks, with the dominant bird cowing the others. Photo copyright Paula Halford.

The two chicks have been flying for about two weeks now and one of the adults (the other has departed the scene) takes them off hunting through the day. The magpies and peewees were always bombing the parents now the chicks have a bit of sport of an afternoon returning the favour!

Such stunning raptors! Paula’s two juveniles on a fence. Young Spotted Harriers fledge in four to six weeks. Photo copyright Paula Halford.

I never tire of watching them swooping and dipping with their five black wing tips curled outspread with the sunlight coming through. They are an awesome sight. Yellow legs, striped tails and spotted plumage and such a regal head. I think one of the chicks is a male — he is bigger and much more demanding than the other!

As an adult this bird will develop a beautiful smoky-grey and chestnut plumage. Juvenile Spotted Harriers have been known to disperse or migrate up to 1,600 km. Photo copyright Paula Halford.

We’ll be sorry to see them go and just hope they will come back again to the same next next year.

Adult Spotted Harrier in flight. A solitary harrier of crops, grassland, low shrubland and open woodland in inland and northern Australia. These birds usually sail low to the ground in a buoyant style, with gentle rhythmic wing-beats and extended glides. Photo copyright Bruce Thomson.

See more of Bruce Thomson’s great images here.

To see something of Paula, and other people’s, great work in conserving the Grassland Earless Dragon, a rare reptile of the Darling Downs grasslands, see:

Spotted Harrier

March of the Mysterious Moon Ants

The mysterious twilight procession begins. Up the driveway, across some steps and along our paved area with relentless purpose. Photos taken by Rob and Harry Ashdown on Canon Powershot G10 and G12.

Every summer, about twilight, when the throaty rumble of newly-emerged Bladder Cicadas fills our ears, a strange procession happens outside our back door. Large ants wander up from the driveway, always heading in the same direction — across the back paved area in the direction of our neighbours’ house.

Banded Sugar Ants on the go. Sugar Ants come in many shapes and sizes, and are named after their habit of collecting sugary plant secretions, although most species are also scavengers and predators. Many Brisbane species are nocturnal.

We’ve come to call them Moon Ants, for some reason, probably because they come out only at night, and we’ve watched them in the moonlight (as you do). We quizzed Susan about them when she visited a few years back. Susan’s a guru of all things entomological, which she should be, as she’s an entomologist at the Queensland Museum in Brisbane. She filled us in. These are Banded Sugar Ants (Camponotis consobrinus), members of the largest genus of ants in the world, a group that comprises thousands of species, of which at least 20 are found in the Brisbane area.

Sugar Ants differ from other ants in several ways, according to the Queensland Museum’s wonderful guide to ants (seriously, this is a fabulous book). Most have no metapleural gland (you knew that I’m sure), and they lack its associated opening above the base of the hind leg (you probably knew that too). There’s more. They have a single segmented waist and the mesosoma and petiole lack spines (I knew that … well, I do now). Workers don’t sting, but can spray formic acid into a bitten area. Ouch!

Although big and fierce looking, Banded Sugar Ants don’t sting, but they can bite, although we’ve yet to be savaged by any. They fare rather worse in our encounters, often getting flattened by foot traffic out the back at night.

A Banded Sugar Ant pauses to inspect the body of an unfortunate colleague, tragically flattened by the giant feet of blundering humans.

Last year we went on a mission to track down their nest site, which we found under some old railway sleepers alongside the driveway. We didn’t disturb them, and although most people have a fair amount of disdain, or even hostility, for ants, I reckon they are terrific. We always like watching their purposeful march past our back stairs. Another piece in the jigsaw of our strangely diverse suburban backyard.

- More about Sugar Ants, and everything else, from the Queensland Museum’s website.

- A fabulous book about Brisbane’s ants, from the same bunch of natural history gurus. Written, with clear enthusiasm and riddled with an abundance of fascinating facts, by Dr Chris Burwell — and with insanely good photography by one of my favourite photographers (and old mate) Jeff Wright. A must-read for any natural historian.

Topknots drop in

I’ve shown some great images of ospreys from Ross Naumann in a previous post. Ross recently sent me these photographs of Topknot Pigeons in a piccabeen palm at his home on the Sunshine Coast.

The Topknot Pigeon (Lopholaimus antarcticus) is usually a rainforest bird, whose numbers have declined along with the reduction in their favoured habitat on Australia's east coast. Immense flocks were seen by Captain Cook's crew at Cooktown in 1770. Today, flocks seldom number more than 200 birds and are usually less than 50. All photographs copyright Ross Naumann.

“They have been around all week and we have never seen them here at home before (since 1996),” says Ross. “Very flighty — they take off as soon as you open a door. I took these through glass from our laundry (pilkington glass + Canon optics = reasonable result).

Topknots move from place to place to follow fruiting trees, with some flocks travelling along the entire length of the Queensland coast.

They were back a few days later. “Yes, our feathered friends returned this morning. The tell-tale heavy flapping together with seed dropping makes it a no-brainer to identify their presence. Still more scared than a coulrophobic at a clown convention (or your local burger place). How do you convey to these animals that you mean no harm? Maybe put RSPCA or WWF stickers on the windows? We have been seeing up to twelve birds in a flock.

One of the great things in (wild) life is that you never know what will turn up next.”

Topknots have an elaborate courtship display, during which the paired birds entwine necks while their crests are fully erect. A complex bowing follows.

When feeding, Topknots characteristically hang upside down, flapping wings loudly and dislodging clouds of fruit.

Boondall Birds

Some more photos from my brother-in-law, Mike, all taken at Boondall Wetlands, Brisbane. Think I need to convince him to set up his own blog.

Welcome swallows, late afternoon

Late afternoon, Queens Park, Toowoomba. A smoky western horizon and setting sun, workers busy setting up a fairground for the Carnival of Flowers. Sitting with lad and dog watching Welcome Swallows, also busy, hawking for insects over freshly-mown fields. They weave and duck and twirl around us, too fast for the eye to see what they are doing, the dog just wants to chase them. They catch insects and chase each other, a network of tiny lives lived fast and furious. We enjoy watching them and taking turns trying to photograph them (the dog declines) by panning with a compact camera, a hopeless but fun task. The images are grainy and dodgy of course, but they give an impression of the afternoon.

Queens Park, Toowoomba. Bushfire smoke blankets the western horizon. The foreground looks empty, but it’s alive with activity. Photos by Harry and Rob Ashdown.

Welcome Swallows, Danielle Davis

Kingfishers

Kingfishers and Kookaburras! Vibrant in color, conspicuous in activity and often hilariously raucous, these are some of the most well-known and much loved birds in Australia! Kingfishers and kookaburras are a versatile group. Their colours range across the spectrum. They have adapted to rivers and deserts, to wet rainforests and dry woodlands, to mangrove swamps and islands. They catch lizards, snakes and spiders on the ground, dive underwater for fish, snatch frogs in the tree canopy, and take insects in full flight. — Online review notes of ‘Kingfishers and kookaburras: Jewels of the Australian Bush’, by David Hollands.

There are ten species of kingfisher in Australia. I’ve only seen a few of them, but recently laid eyes on a personal new species — the Red-Backed kingfisher (Todiramphus pyrrhopygia) on the Darling Downs.

Red-backed Kingfisher (Todiramphus pyrrhopygia), Mount Tyson, Darling Downs. Thanks to spotter extraordinaire Rod Hobson. Photo R. Ashdown.

Red back of the Red-backed Kingfisher. These kingfishers inhabit the dry, inland regions of Australia, usually desert, mulga and mallee country. A nomadic species, in dry winter months they may migrate northward or towards the west and north-eastern coast. Photo R. Ashdown.

Whether or not I’ve a camera in hand, it is always a thrill to watch kingfishers. The fleeting, dazzling blue of an azure kingfisher darting across a dark, quiet creek or a muddy mangrove bank seems to me to be like the last piece of a scene’s jigsaw falling into place.

Azure Kingfisher (Alcedo pusilla), Tingalpa Creek. Australia’s smallest kingfisher, with a bill that takes up more than a quarter of its 19cm body length. Photo R. Ashdown.

I’ve always found these birds difficult to photograph. The best results, as is always the case, come with knowing your subject, having incredible patience, and often using a hide and having a big bit of glass stuck to your camera. I haven’t used any of these when it comes to kingfishers – I’ve always ended up in a muddle just snapping away, usually with fairly ordinary results. I did discover that you can get fairly close to kingfishers by using a canoe to sneak up on them – that’s how I took these images of an Azure Kingfisher (above) and a Collared Kingfisher (below) on Tingalpa Creek, where Brisbane’s outskirts meet Redland Bay.

Collared Kingfisher (Todiramphus sanctus), Tingalpa Creek. Sometimes referred to as the Mangrove Kingfisher, this bird lives in the mangroves of Australia’s northern coasts. It eats insects, reptiles and aquatic animals such as worms, which it picks off the mudflats. Photo R. Ashdown.

Through patience and persistence, Mike Peisley has captured taken some excellent images of sacred kingfishers in his local patch of scrub in Brisbane.

Sacred Kingfisher (Todiramphus sanctus). This is the most familiar, and widespread, of the Australian kingfishers. It spends its day watching for insects and lizards in the leaf litter, but sometimes dives into brackish water for fish or yabbies. This species is found all over Australia, except in the densest rainforests and inland deserts. Photo M. Peisley.

Finally, here are some more images of these adaptable and exquisite birds using any available perch.

Forest Kingfisher (Todiramphus macleayii), northern Queensland. A bird with royal blue wings, the Forest Kingfisher is a bird of open woodlands, swamps, mangroves and gardens. Photo R. Ashdown.

Laughing Kookaburra (Dacelo novaeguineae), Bellthorpe State Forest. A common visitor to Australian gardens, this large kingfisher of the southern and eastern states has been introduced and established in Western Australia, Tasmania and New Zealand. Photo R. Ashdown.

Challenging and enchanting subjects indeed. For anyone seeking a complete immersion in the magical world of Australian kingfishers, track down a copy of the book mentioned at the start of this post: Kingfishers and Kookaburras: Jewels of the Australian Bush, by David Hollands, is a book that truly captures the magic of these birds in all their variety.

Pacific Bazas

More photos from friends! Mike Peisley’s patience in watching Pacific Bazas at Boondall has paid off with some wonderful images, which he has generously allowed me to post.

Pacific Bazas, or Crested Hawks (Aviceda subcristata) visit Brisbane in numbers during early winter to mid-spring. These striking raptors have a distinctive ‘whee chu’ call, which is often heard during breeding season.

The sole Australian representative of a hawk group known as the Cuckoo Falcons or Lizard Hawks, Bazas feed in treetops, where they snatch small prey such as frogs and insects such as phasmids (such as Mike captured here). Their eyes contain particular oil drops that allow them to spot green prey among foliage.

During the breeding season, Bazas call, soar and carry out dramatic display flights. Outside the breeding season, they can be secretive and difficult to spot.

For more information on these birds, see the Queensland Museum’s information sheet (PDF download).

Mangroves at dawn

Echidna on the move

A beautiful, impressionistic image of a young echidna on the move on a sunny spring morning.

Echidna search!

Although the echidna is Australia’s most widely distributed native mammal, very little is known about this egg-laying mammal. A study of echidna reproductive behaviour is underway and the University of Queensland is seeking information of sightings of echidnas in the south-east Queensland area. If you see a live or dead echidna please contact Trish LeeHong.

Peregrine up close

While on a break from his job as an air traffic controller, Mike Peisley spotted a peregrine falcon flying outside the tower. Luckily he had a compact camera with him, and grabbed these images of a spectacular raptor as it landed on the ledge outside the window.

Peregrine Falcon (Falco peregrinus). One of Australia's six falcon species. The specific name comes from the word 'wandering' and alludes to the migratory nature of Peregrines in the northern hemisphere. Australian adult Peregines, however, are not migratory. All photos copyright M. Peisley.

Mike explains how he got the images:

The peregrine approached the tower and zoomed up a bit looking inside, paused and landed on the balcony behind the controllers on duty.

Luckily I was on a break and grabbed my compact camera. The control tower is about 70m high at our level with 25mm thick glass windows. I approached the back of the tower cautiously trying not to spook him as the peregrine was tilting his head and either looking up at his reflection or trying to look inside.

The Peregrine is a compact, heavily-built falcon, stockier than other Australian falcons. It is characterised by short tarsi (the lower part of the visible section of the bird's leg, below the ankle joint - the true knee is hidden by feathers), large feet, and long toes.

Peregrine Falcons are found throughout mainland Australian and Tasmania. They are solitary, aggressive falcons found in most habitats but usually seen near cliffs, escarpments and wetlands. They fly and soar strongly at great heights and stoop with closed wings in a bullet-like shape. They are capable of striking down quite large birds and often feed on the ground.

From about 5m away I got the best views and pictures I am ever likely to get. What really surprised me was the size and menacing look to his claws — I was thinking velocoraptor.

Peregrines nest solitarily in stick nests of other raptors in trees or on a scrape on a quarry or cliff edge. They also nest on structures such as buildings or silos (maybe this one was checking nest site possibilities). Usually three or four eggs are laid between August and October. Young birds are dependent on parents for two to three months after fledging. Young can remain in the nest area for up to eight months, but then disperse widely (up to 500 km has been recorded, usually about 60 km for males and 130 km for females).

It was a real treat and I felt very lucky to have seen him so closely. He stayed for about 3 minutes, walking a few meters along the balcony, stopping and looking again in the glass. In more than ten years I have never seen a peregrine (or any prey bird) land on our balcony and only perhaps one or two cruise past per year.

The Peregrine is not globally or nationally threatened, and has increased in urban and agricultural areas in Australia since DDT was banned - this insecticide reduced the thickness of eggshells and numbers of these falcons declined. They are still heavily (and illegally) persecuted by pigeon-fanciers. Information from The Birds of Australia, A Field Guide by Stephen Debus.

More birds and mirrors

A Yellow-bellied Sunbird (Nectarinia jugularis) challenging its mirror image. Mareeba, North Queensland. Photos by Raelene Neilson.

For previous rear-view action see my post on wrens.

Zoonosis — a word of the future

When a pathogen leaps from some nonhuman animal into a person, and succeeds there in making trouble, the result is what’s known as zoonosois. It’s a word of the future.

‘Deadly Contact — How Humans and Animals Exchange Disease’,

National Geographic, October 2007

Too many words have been written about flying foxes, horses and the Hendra Virus for me to add many more about the whole thing here. This is a serious issue, and while I like humans, I also like flying foxes. They are interesting, important animals. Unfortunately the voices of reason and research have been largely buried by dodgy reporting and public ignorance — about the virus and about flying foxes. One thing seems clear — flying foxes, which carry the Hendra Virus and somehow transmit it to horses, from where it is passed on to humans, are in trouble.

Four species of flying-fox are native to mainland Australia. The Little Red (left) and the Grey-headed (right) are two of those found in south-east Queensland. Flying foxes make a significant contribution to maintaining healthy ecosystems as essential pollinators and seed dispersers for native forests. Our eucalypt woodlands rely heavily on these pollinators, producing most of their nectar and pollen at night to coincide with the time when bats are active. Photos (left – Gatton, right – Allora) R. Ashdown.

There has been little information in the media about the link between human-caused disruption of ecosystems and the emergence of zoonotoc diseases, despite ongoing research overseas and in Australia. Flying foxes are mammals whose ecology has been greatly affected by human impacts on the environment, and this has almost certainly been a link in the emergence of this disease. The National Geographic article from which the quote at the start of this post was sourced gives an excellent look at the complex and poorly understood history of the transfer of viruses between humans and non-human animals. This is too important an issue for people to be mindlessly calling for the destruction of wildlife without looking at the big picture — which includes why these diseases are occurring and how our impacts on the environment are part of the cause.

If you’ve read this far you’re probably a wildlife-person, so it’ll be no surprise if I say that culling flying foxes is probably not going to help.

Although Hendra virus infection occurs naturally in flying foxes, these animals should not be targeted for culling. Flying foxes are protected species and are critical to our environment, as they pollinate our native trees and spread seeds. Without flying foxes, we wouldn’t have our eucalypt forests, rainforests and melaleucas. Any unauthorised attempt to disturb flying fox colonies is illegal. Disturbing flying fox colonies to reduce the risk of Hendra virus transmission to horses is ineffective because:

- flying foxes are widespread in Australia and are highly mobile

- there are more effective steps people can take to reduce the risk of Hendra virus infection in horses and in people

- attempts to disturb or cull flying foxes could worsen the problem by stressing them and potentially causing Hendra virus excretion.

Department of Primary Industries and Fisheries

This is part of a larger story for all of us — for humans and for other species of life.

Our safety, our health, isn’t the only issue. Another thing that is worth remembering is that disease can go both ways: from humans to other species as well as from them to us. Measles, polio, scabies, influenza , tuberculosis and other human diseases are considered threats to non-human primates. Any of them might be carried by a tourist, a researcher, or local person, with potentially devastating impacts on a tiny, isolated population of great apes with a relatively small gene pool, such as the mountain gorillas of Rwanda or the chimps of Gombe.

That’s why the Wildlife Conservation Society label their program with the slogan “One World, One Health.” The guiding principles come from ecology, of which human and veterinarian medicine are merely sub-disciplines. “It’s not about wildlife or human health”, Billy Karesh told me. “There’s really just one health” — the health and balance of ecosystems throughout the planet.

‘Deadly Contact — How Humans and Animals Exchange Disease’,

National Geographic, October 2007

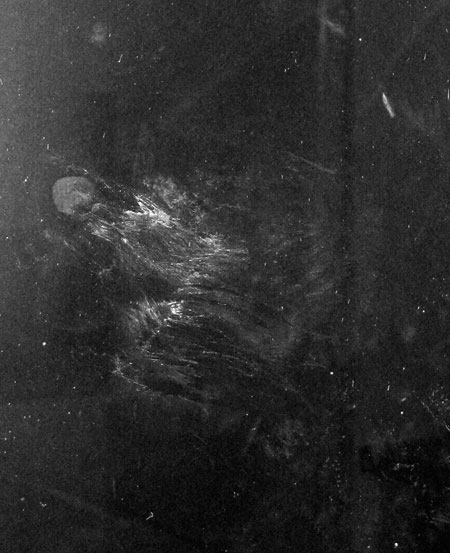

Wings in the night

The word ‘ghost’ appears again in my dodgy blog, what’s going on? I’m developing a fascination with the supernatural … or not.

This image was discovered on our front window at work one morning, on a main street of Toowoomba. It isn’t a ghostly apparition, it’s powder down left on the glass by a Tawny Frogmouth (Pogardes strigoides). The bird wasn’t dead on the footpath, so hopefully it survived its run-in with the glass.

Often mistaken for owls, Tawny Frogmouths are a member of the bird order Caprimulgiformes, which includes four families of related species, including oilbirds, owlet nightjars, potoos and nightjars. They are common nocturnal birds in our town, seldom seen but sometimes heard (their call is a quiet ‘oom, oom, oom’) and I sometimes find them dead on the roads in the morning after they’ve bit hit by cars— they are largely insectivorous and too often hang around streets in search of insects attracted to streetlights.

A Tawny Frogmouth near the centre of Toowoomba. While they are nocturnal birds, frogmouths are not owls. They are sometimes called Mopokes, a mistaken reference to Boobook Owls, which are the night birds that make the ‘mopoke’ call. Unlike owls, frogmouths have short, weak legs and feet. These birds have adapted well to urban areas in Australia. Photo R. Ashdown.

Unlike most other birds, tawny Frogmouths do not have preen (oil) glands. Instead, they have two large patches of powder-down on each side of their rump that helps make their feathers waterproof. With some bird species, the tips of the barbules on powder down feathers disintegrate, forming fine particles of keratin, which appear as a powder, or “feather dust”, among the feathers. In other species, powder grains come from cells that surround the barbules of growing feathers.

The recent extraordinary powder-down silhouette left on a window by a tawny owl (Stric aluco) in England made it onto at least ten blogs and news sites in July this year.

“For the Unholy Underpants of Voldemort, what bollocking sorcery is this?” That’s probably what Sally Arnold thought when she arrived to her house and saw this perfect image of an owl over the window. How did this spookiness happen? See the extra-spooky image here or even here.

More on Tawny Frogmouth here.

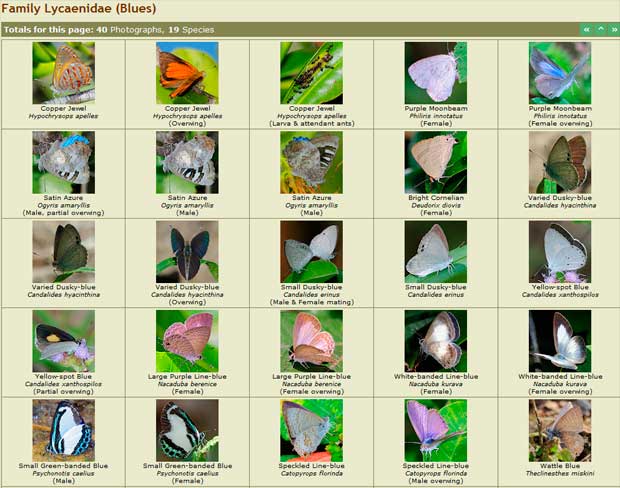

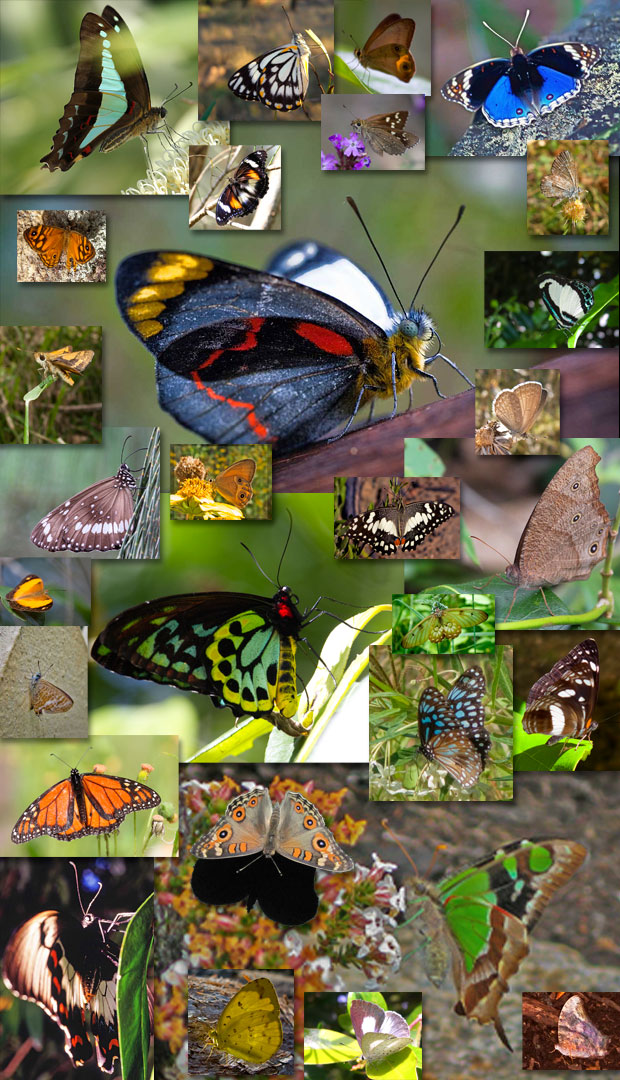

Butterflies

Winter has suddenly gone, and I managed to not make a single blog post the entire season. Too busy staying warm, or working or other stuff. A lone fluttering Common Jezebel (Delias nigrina) in the backyard last week reminded me that I had meant to post about the profusion of butterfly life in town prior to the onset of the cold. I checked my backyard list and I had not recorded this species in my backyard before, even though it was a common viistor to our yard in Brisbane, where its larvae would feed on the native mistletoe in the plants around the suburb. My Toowoomba backyard list now stands at 24 species.

Common Jezebel (Delias nigrina)

Images of four other species spotted in the yard this year.

Butterflies are a favourite subject for natural history photographers around the world. Photographer Ulf Westerberg has has just published Fragile Wings — Secrets of Butterflies and Moths, a wonderful photographic exploration of Sweden’s butterflies. It has some of the most spectacular butterfly images I have ever seen. A selection of these wonderful images can be viewed here.

Bengal Butterflies is a spectacular website dedicated to the butterflies of West Bengal. Photographer Ujjal Ghosh states on his site that the world has approximately 17,000 recognised species of butterflies, India has 1,501 and West Bengal may have up to 600 species!

If you have time check out the page where you can send an email greeting with one of his spectacular butterfly images attached. Ujjal has another website of natural history images, which can be seen here.

There are many websites dedicated to Australian butterflies. While we have between 20,000 and 30,000 species of moths, Australia has only about 416 butterfly species. Butterflies haven’t adapted well to the arid conditions of this continent.

One of the most comprehensive and informative Australian butterfly websites is the Lepidoptera/Butterfly House website. The Butterfly and Other Invertebrates Club is a Brisbane-based group with a great website on Australian butterflies (and other invertebrates of course).

A site that I particularly like comes from Deane Lewis. Like Ujjal’s site, it is also a visual treat. Deane also has an incredible collection of images of other invertebrates and wildlife. Check out the website here.

Butterflies are brilliant, and any naturalist or photographer can be forgiven for becoming totally obsessed with these wonderful creatures. As Ulf states in his book, “Butterflies have fascinated mankind since the dawn of time.” I hope it’s another great year for the local butterflies.

Return of the ghostly Ghost Fungus!

Back in June 2010 I posted an article on naturalist Rod Hobson’s discovery of the fascinating glow-in-the-dark Ghost Fungus (Omphalotus nidiformis) on the edges the Toowoomba escarpment in eucalypt woodland.

Fungi are always fascinating, but the Ghost Fungus really stands out — especially at night. A chemical reaction between fungal enzymes and oxygen causes a ghostly, and quite powerful, luminescence.

In December of 2010 I was walking with my 10-year old son in some urban bushland not far from home, when he drew my attention to a large patch of fungus on a tree stump, saying they looked like the Ghost Fungus. I was pretty sceptical, but we returned that night and sure enough, a mysterious ghow could be seen from a fair way down the track as we approached. Spectacular and enchanting stuff.

I did not photograph them then, and when I returned in early January, there was no sign of them on the stump at all. As Rod reminded me, what we see as a fungus is only the fruiting body of the organism, with the main part invisible within the bark of stump or in the ground. Still disappointing though. Show yourself, fungus!

After outrageous amounts of rain, and even floods through the rest of this year (flood, what flood?), the fungi magically reappeared, bigger than ever, so last night I set out with Harry in the howling wind and rain to see if we could sneak up and capture some images of the elusive things glowing away happily.

Yes, they were indeed glowing, but capturing them was not easy, despite their sedentary nature. Howling gales looked set to bring trees down, and rain pelted us. For some bizarre reason scrub ticks were out in this weather and Harry ended up taking one home with him, firmly attached (the trials of the assistant).

After answering the lad’s reasonable question about how I would work out an accurate night exposure of barely-visible fungi in near cyclonic conditions (“Textbook mate — mess about with tripod, attempt to focus, set on manual, guess an f-stop, open shutter, count to a hundred, then count to a hundred again, close shutter, peer at screen, curse and mumble, repeat process with different variables etc etc.”) we took a few photos, with the hapless kid holding an umbrella over me, the camera and the fungus. It got wearying, with little result, and constant water all over the lens. “Just one more,” I said, and we sat and counted erratically to two hundred again. “It’s completely bloody black!” I moaned, looking at the resulting image on the screen. “Dad,” came a weary and mildly astonished voice, “you’ve still got the lens cap on!” Hmmm.

Groan, one more try. Lens cap OFF, fumble for cable release, shutter open. Start counting.

Success at last. The Ghostly Ghost Fungus on a stormy, haunted night. Exposure details — removed lens cap, set aperture to f something (forget), count to maybe 200. Photo by HARRY and Robert Ashdown.

Eventually we got two shots that worked, and back home we both agreed it was worth the uncomfortable excursion. What a mysterious, magical, and even ghostly thing fungi are!

Other glowing stuff:

- Hunting the Ghost Fungus (The Guardian)

- Ghost Fungus in the Blue Mountains – Lyreades Nature Blog

- Luminescent fungi at Mount Gravatt in Brisbane.

- Foxfire Forest Constellations

- Bio-luminescence at Gippsland Lakes in Australia – insane images!

- Bio-luminescent millipedes

Some Australian fungi facts:

- There are approximately 250,000 species of fungi in Australia, of which possibly only 10% have been scientifically described and named. There are at least 71 known species of luminescent fungi in the world, with six of those found in Australia.

- Healthy ecosystems need healthy, diverse populations of fungi. About 95% of terrestrial plants depend on specific fungi (mycorrhiza).

- Many fungi are an important food source fo Australian animals, with at least 38 species of mammals known to eat the fruiting bodies of fungi. Some species, such as bettongs and pottoroos, eat little else.

- Fungi reproduce by releasing clouds of powder-like spores from their fruiting bodies. A field mushroom can release 200 million spores in a single hour. Puffballs can produce 15 trillion spores from each fruiting body.

- Some fungi are pathogenic, causing disease and the death of various species. However, in nature, this helps to makwe room in ecosystems which new species can fill.

- Many fungi are decomposers, releaseing nutrients by breaking down dead plants and animals — a vital part of forest ntrient cycles.

- A fungus is usually largely out of sight, with only the fruiting bosy exposed to view. The remainder, thin threads called mycelium, is underground or webbed throiugh soft, rotting, wood.

Australian fungi websites:

Pipeline rescues

I’ve mentioned Steve Wilson in previous blog posts, but he probably never reads these posts so his ego won’t get any larger (a failing of many herpetologists and lots of naturalists, except me of course).

Steve’s been working out west, on and off since 2008, employed by gas companies to rescue animals that have fallen into the deep trenches built to take pipelines. It’s hard and dangerous work, with anything from enraged Eastern Brown Snakes to confused cows ending up in the trenches and having to be removed. The good side of it for Steve is getting to see some interesting reptiles. The image is of Steve with a Woma, one of Queensland’s larger and more uncommon pythons.

I haven’t asked Steve how many animals he and co-worker Gerry Swan have pulled out of trenches, but it must be an enormous number. Between November 2008 and March 2009, a total 2,790 animals (comprising 96 species) were recorded from one trench alone. There were plenty of snakes in that list, with 323 individuals of 24 species recorded.

Steve provides data on the animals recorded to the Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service, for logging on the Agency’s Wildnet fauna mapping system.

I’ll see if I can talk Steve into a few words about his recent finds for a future post.

More stuff: