Lake Nuga Nuga, the largest natural water body within the dry highlands of the Central Queensland Sandstone Belt, is a place of many stories.

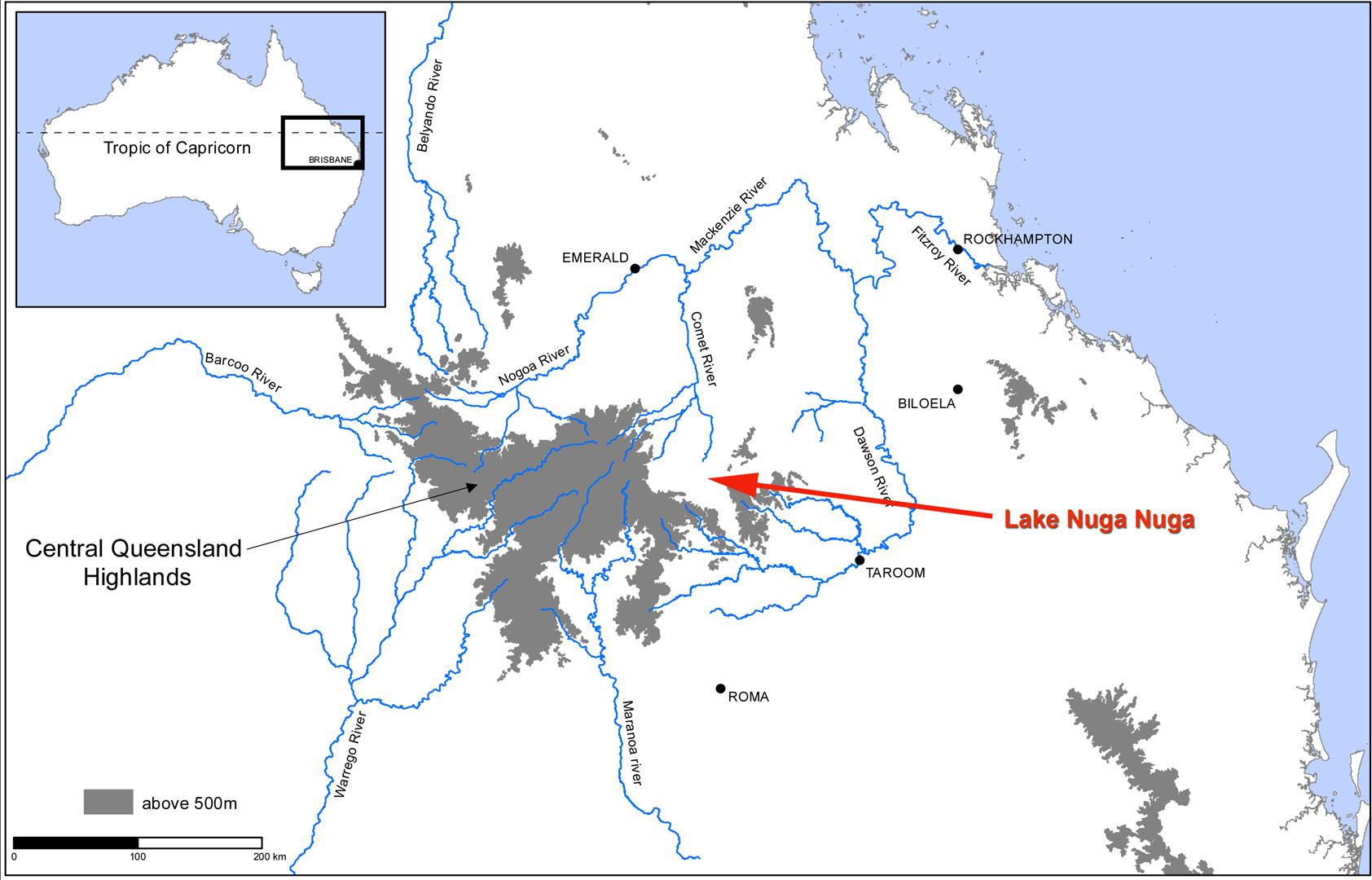

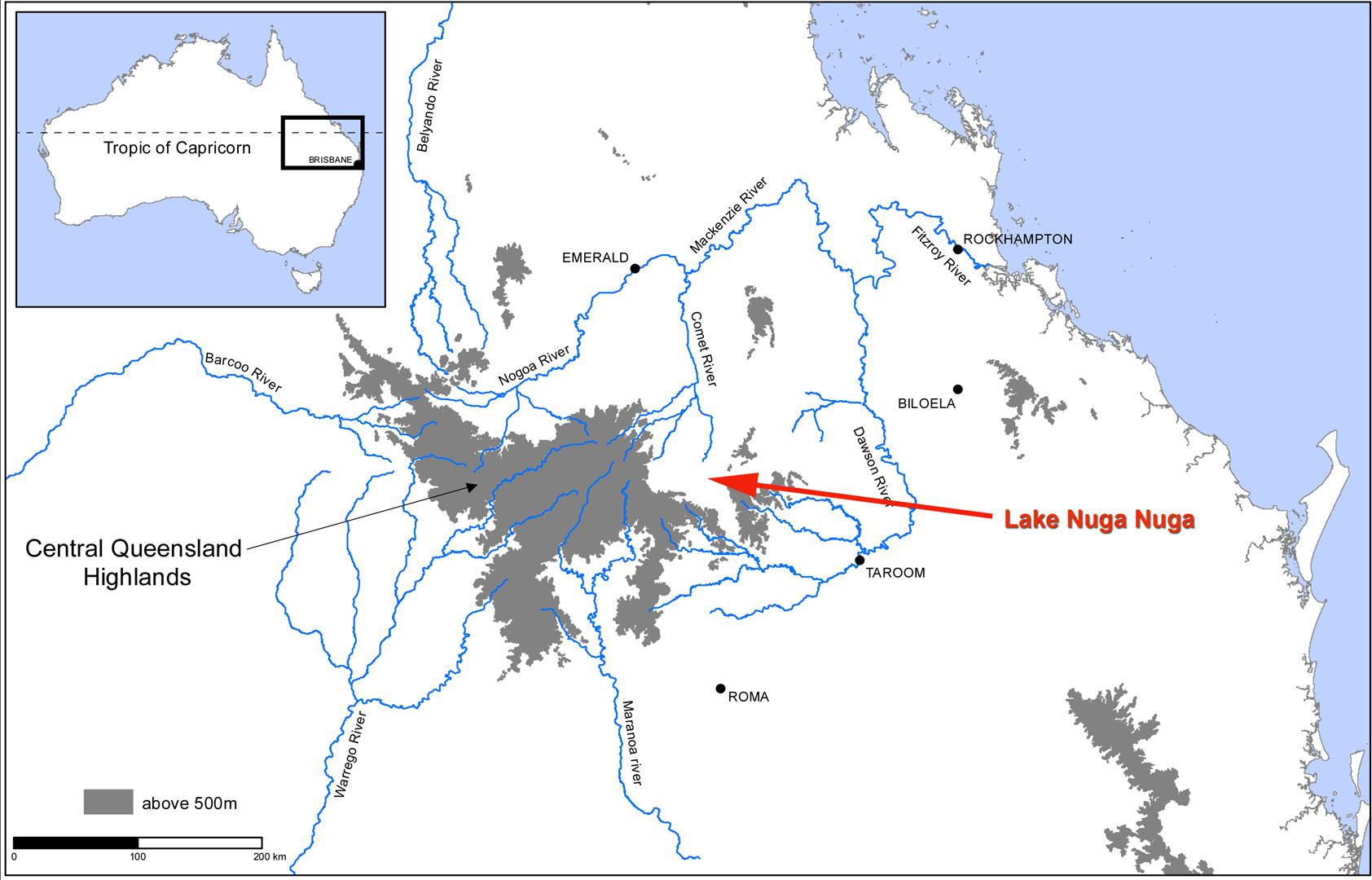

About 515 kilometres north-west of Brisbane, this lake is located at the northern (downstream) end of the Arcadia Valley, and lies within the floodplain of the Brown River, a tributary of the Comet River. The Comet River itself falls within the greater Fitzroy River basin (see map below), the waters from which eventually reach the Queensland coast near Rockhampton.

During favourable seasons both the Brown River and Moolayember Creek flow into Lake Nuga Nuga.

Standing dead trees in Lake Nuga Nuga are illuminated by campfire in a three-hour exposure (taken on on slide film). All photographs in this post by Robert Ashdown unless credited otherwise.

Lake Nuga Nuga varies in size with the seasons. It is usually somewhere in the order of about 2,000 hectares in area, and is about eight kilometres across in a north-west to south-east direction and about four kilometres in width. The lake is mostly below two metres in depth, with a maximum depth of about nine metres. One source records the lake as having been dry only twice — in 1936 and in 1970–71, while Walsh (1988) states the lake as having been dry three times during the 1970s and 1980s.

Nuga Nuga National Park lies adjacent to the lake’s northern banks, but does not include the lake itself.

Lake Nuga Nuga is located within the Central Queensland Highlands, an elevated area of sandstone ranges and wide valleys.

Five major river systems have their origins in this sandstone country. The area is sometimes referred to as ‘The Home of the Rivers’.

Looking east over Lake Nuga Nuga toward the Expedition Range. Nuga Nuga National Park, which covers the northern edge of the lake seen here, includes some uncleared remnants of the Arcadia Valley’s original vegetation.

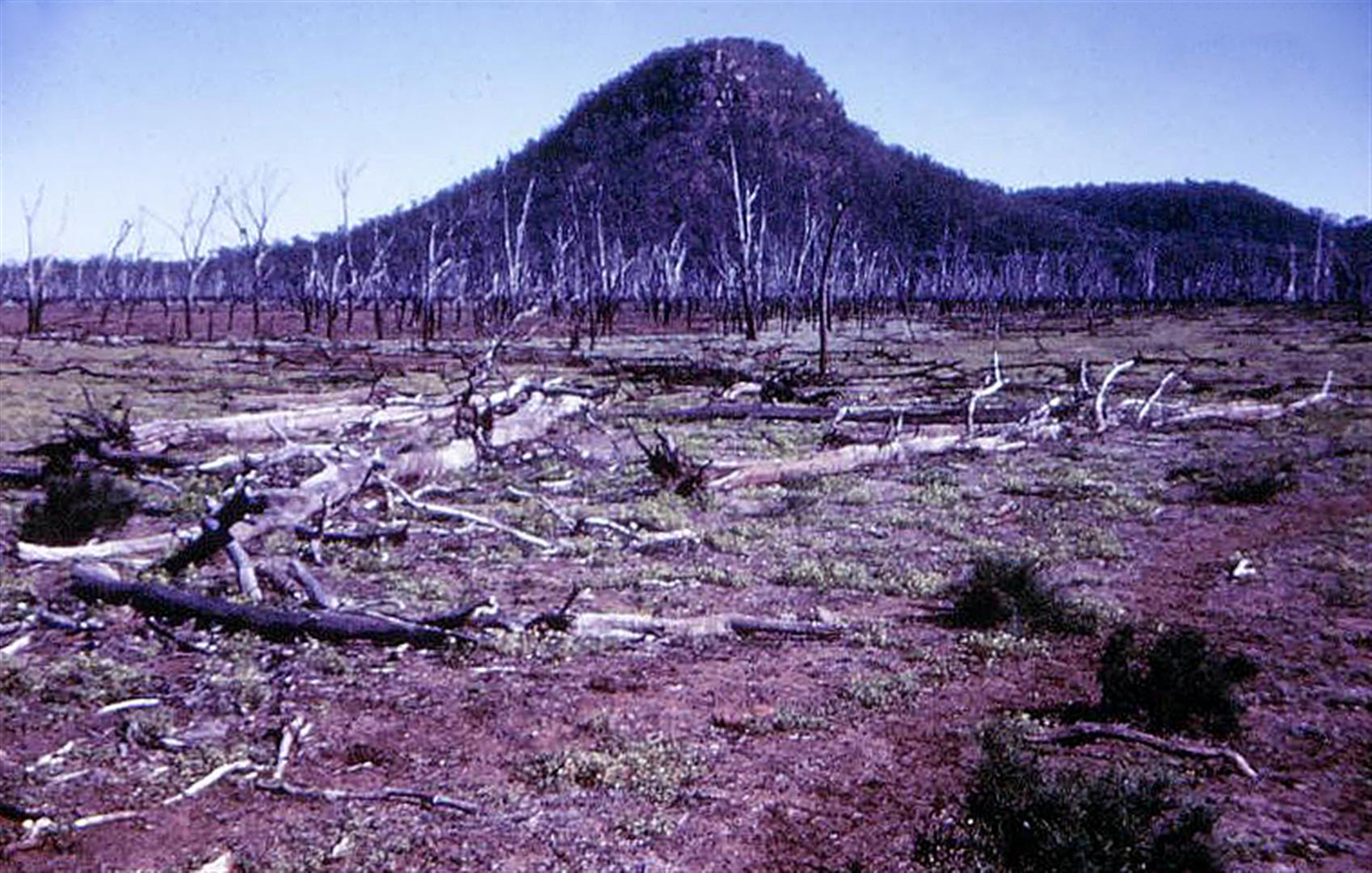

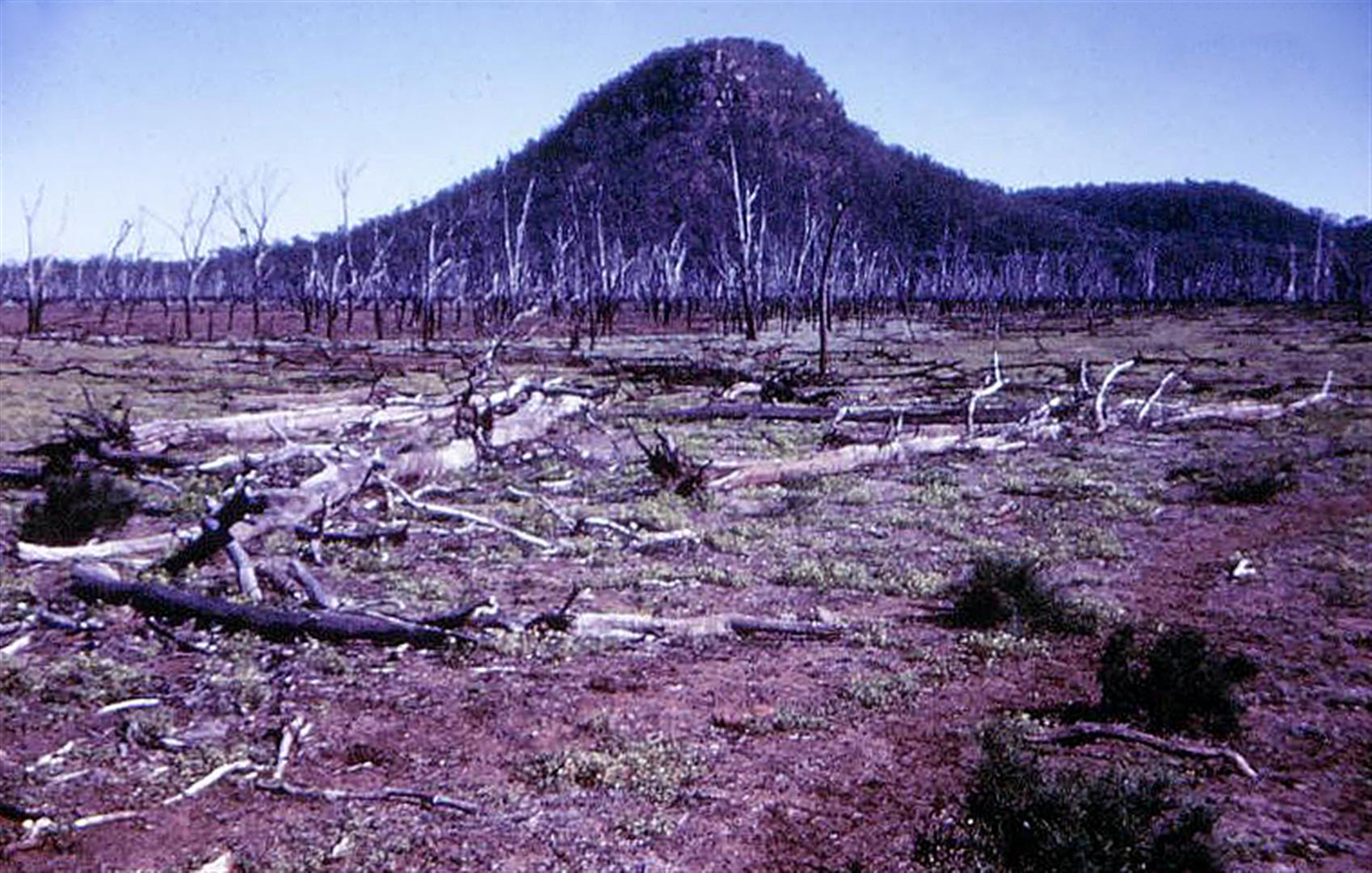

Lake Nuga Nuga nearly dry. Photograph taken in the 1950s, courtesy Bill Goebel.

Mt Warrinilla, Lake Nuga Nuga, 1950s. Photograph by Bill Goebel.

A sudden growth …

While today’s visitors to the lake are often awed by the lake’s immense expanse, it has not always looked like this.

Ludwig Leichhardt crossed the nearby Expedition Range in 1844 on his way to Port Essington. He narrowly missed Lake Nuga Nuga while skirting around the area’s brigalow scrubs. He did name Lake Brown, a lake just to the north of Lake Nuga Nuga, after one of the Aboriginal members of his expedition.

A view west across Expedition National Park, through which explorer Ludwig Leichhardt travelled in 1844. This national park protects an area of original scrub similar to that which Leichhardt would have encountered on this journey.

Walsh (1985) believes that Frederick Walker of the native Police may have been among the first to officially record the lake’s existence in early ‘white’ records.

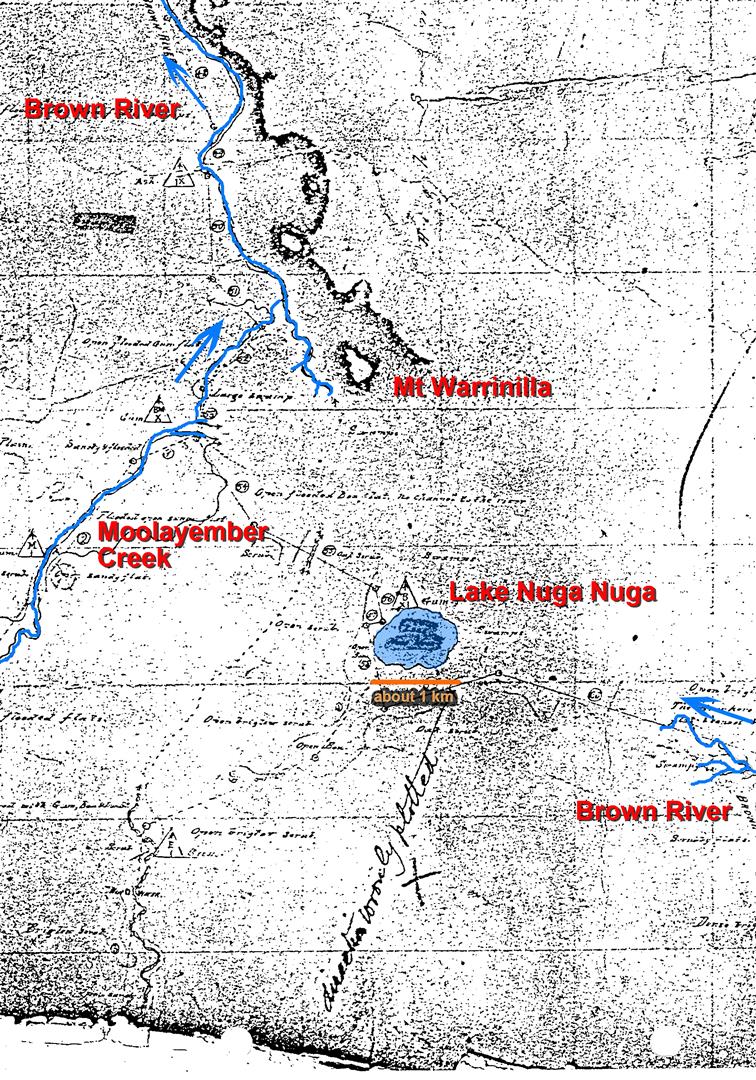

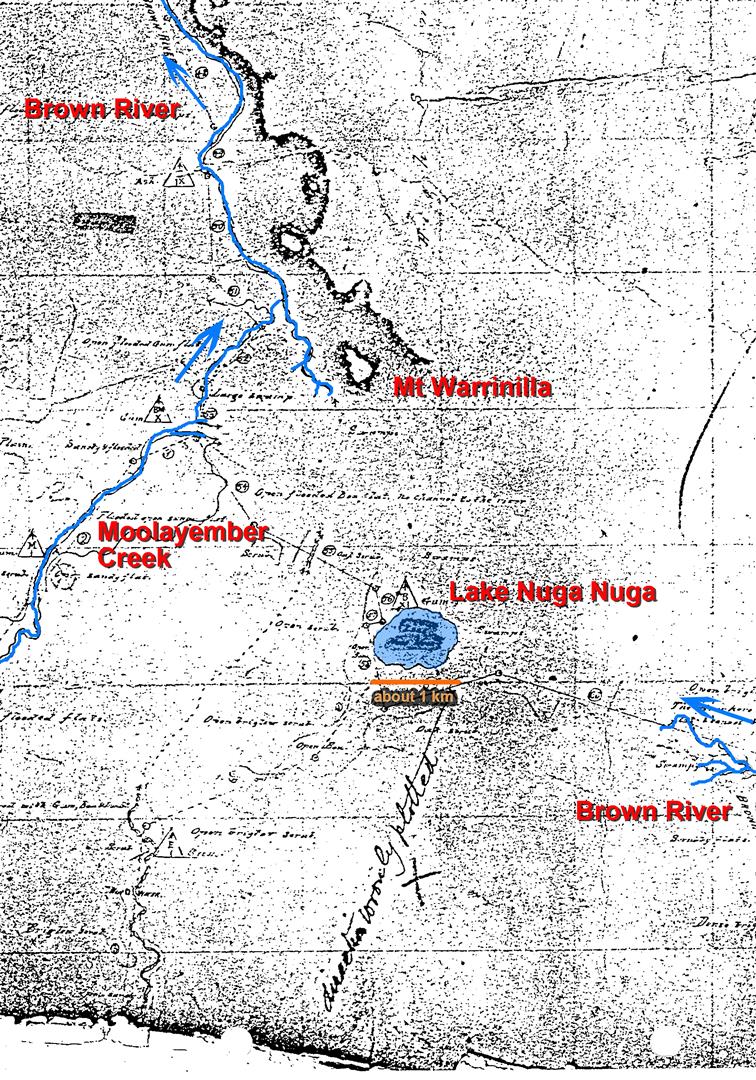

In 2006 researchers Finlayson and Kenyon published a paper on Lake Nuga Nuga, sourcing original files and the results of lake core sediment samples. They studied the records of surveyor Vernon Brown, who travelled through the Arcadia Valley in 1865. Brown recorded Lake Nuga Nuga as small, being only about one kilometre in diameter, within an extensive area of swamps and flood-prone country covered by open forest and ‘open brigalow scrub’, ‘oak scrub’, ‘open scrub’ and ‘open flooded box flat’.

Vernon Brown’s 1865 map of Lake Nuga Nuga. The lake was about one kilometre in diameter and set within an area of swamps. (Coloured notes are my estimations only and may be incorrect).

About 1880 the dimensions of Lake Nuga Nuga dramatically extended over a short period of time.

It is thought that heavy rain and the subsequent flooding of the Brown River filled the small existing lake and surrounding swamps, before a scouring flash flood in Moolayember Creek transported large amounts of silt into the vicinity of the lake. When these waters reached the creek’s right-angle junction with the Brown River, turbulence caused the silt to form a natural levee bank at the lake’s northern end.

Lake Nuga Nuga today, a much larger expanse of water. (Blue colour may not be the current amount of water in the lake, as it recedes and fills seasonally).

Finlayson and Kenyon believe that Lake Nuga Nuga is unusual geographically because it is a particularly large example of a lake associated with a river levee, and also because it is a rare case where the main stream (the Brown Rover) has been blocked by a smaller tributary, here Moolayember Creek.

The many dead trees throughout the water area may support the larger lake’s relatively short period of existence. The lake has, despite expanding and contracting with seasonal conditions, gradually continued to expand.

Looking west from Lake Nuga Nuga. Moolayember Creek, surrounded by a thin strip of vegetation within a largely cleared area, snakes toward the lake (foreground) from the distant Carnarvon ranges.

… and looking back from the other direction (ie, to the east). Lake Nuga Nuga seen in the far distance from the Woolpack, a sandstone outcrop on the Carnarvon Ranges. Photo by Bernice Sigley.

… and a mysterious disappearance

A strange event occurred at Lake Nuga Nuga in the 1940s. The water of the lake apparently drained overnight, leaving the bodies of thousands of dead fish, eels and turtles scattered around the lake’s shoreline.

From the September 13, 1946 edition of the Western Star:

The waters of Lake Nooga Nooga, normally about five miles in diameter and situated just north of the Carnarvon range, have mysteriously disappeared.

The edge of the lake has been steadily receding, and muffled explosions have been heard from the direction of the lake from Christmas Eve, 1944. Last week the manager of Warinilla Station (Mr W Logan) found that only a strip of mud 100 yards by 20 yards remained. Three months ago there were 400 acres of water. Mr Logan said that the water had been disappearing too fast for evaporation to be the explanation.

The explosion, which is believed to have been a subterranean disturbance, killed all the fish in the lake, which was previously well stocked. Mr Logan said: “We found the fish lying dead in the mud around the lake bed. You can still scoop up their bones.”

One theory held in the district is that the disturbance opened a connection with an underground shale layer believed to run through to Springsure about 70 miles to the north-west.

Mr Logan said that he had never heard of the lake being dry before, but evidence of charring on timber of the “drowned forest” which filled the original lake bed indicated that at some time it must have been swept by bushfires.

The drowned forest, Lake Nuga Nuga.

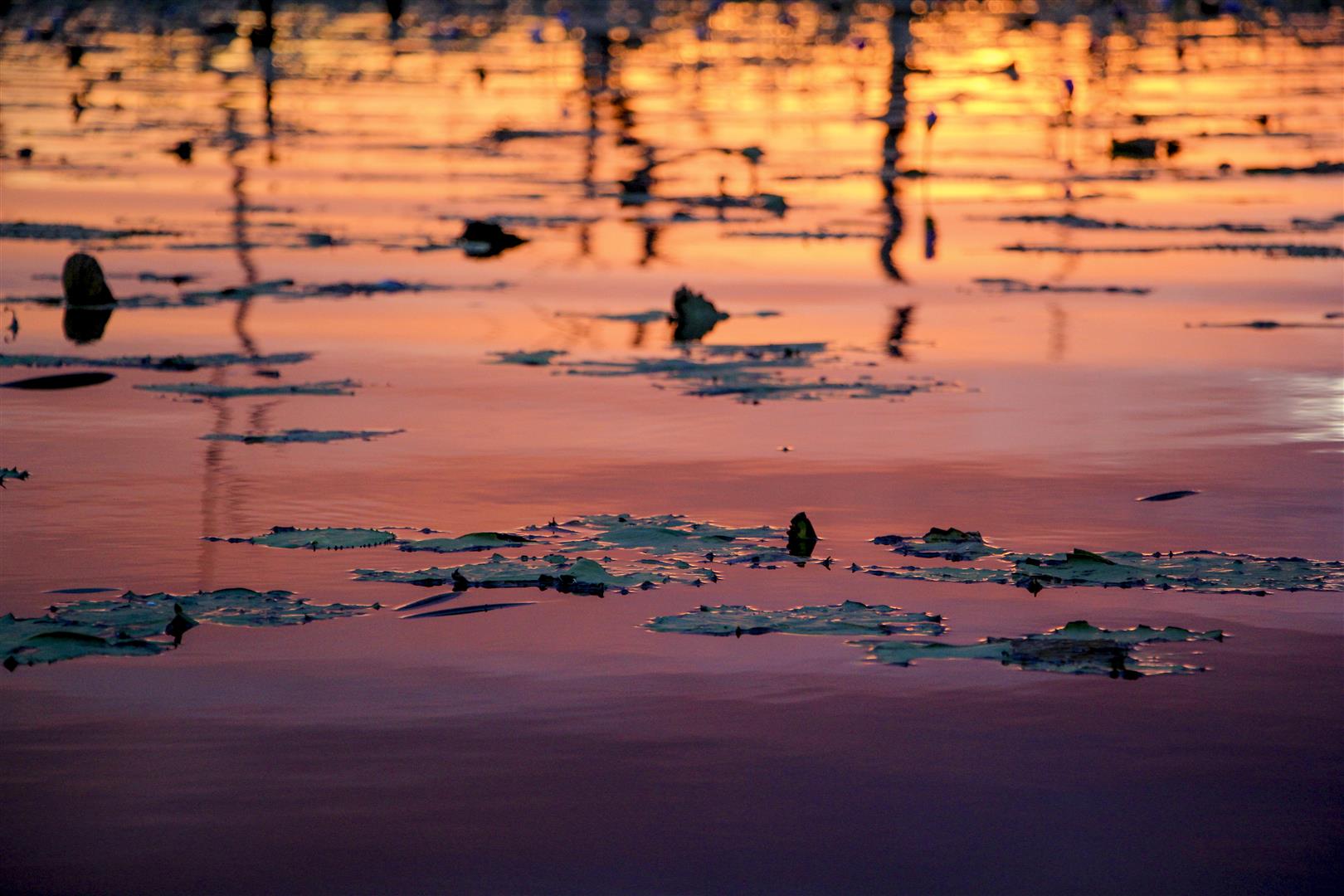

The quiet waters of Lake Nuga Nuga on sunset. Photograph by Linda Thompson.

Walsh (1985) reports one persistent local theory for this event:

It is believed that American bombers flying on the Darwin to Brisbane route had jettisoned their bomb load directly into the lake’s waters. The explosion was thought to have opened some fissure or fault in the floor of the lake and permitted the water to escape. Careful examination of the lake bed during the 1970s drought failed to discover any evidence of such disturbance or of bomb shrapnel.

A squadron of pelicans over Lake Nuga Nuga.

Walsh also quotes a newspaper article about a group on a fishing expedition camped on the lake shore at the time of the event:

The night before, muffled explosions like thunder exploded in the distant hills and rocked their holiday camp and swirled the lake’s waters angrily on its sands.

Apparently activities normally associated with earth tremors were recorded at least as far south as Timor Station, near Injune. It was reported that crockery in the kitchen cupboards rattled furiously in the night in question.

For another explanation, we need to turn to the Karingbal people.

The first people

Lake Nuga Nuga lies within the home country of the Karingbal people. Their name for the lake was, and still is, Wagan Wagan. This means ‘running’ and may have originally referred to the small dotterels and wading birds that can be seen running around the lake’s shoreline.

Karingbal people associate the origin of Wagan Wagan Lake with one of the most significant creatures in Australian Aboriginal mythology, the Rainbow Snake. Within the sandstone belt of central Queensland this creature was known as Moondagarri, Moondungera or Mundagurra. Areas associated with this creature are held in great reverence and the Lake Nuga Nuga area is exceptional in that it is the home of not one but two Rainbow Serpents.

Star trails and Dhanamany (Mt Warrinilla/Round Mountain), beneath which rests one of two Mundagurra (Rainbow Serpents). Lake Nuga Nuga was created to keep the skins of these serpents moist. Should they be disturbed, the Mundagurra will leave the area and the lake will dry up.

The two prominent mountains on the northern lake edge, and which form the southern extremity of the Fantail Range, are known as Mt Warrinilla or Round Mountain — Dhanamany to Indigenous people — and Mt Kirk. One Rainbow Serpent is said to reside under each of these mountains.

Mt Kirk, home of the second Mundagurra.

Lake Wagan Wagan was originally created by the travelling Rainbow Serpents as their final home, and maintain the water in the lake to keep their bodies moist. It is said that if the Rainbow Serpents leave their homes under the mountains the lake will dry up forever.

There was plenty of evidence in the early 1900s that the Lake Nuga Nuga area was of great significance to Aboriginal people long before the advent of European settlers. Writes Walsh:

An extensive complex of ledge burials was found in the area in the 1950s and in spite of its remote location was totally pillaged within a decade, an event all too typical within the entire sandstone country in decades past. A wealth of information was lost to science.

It was a bit more than a loss of information. I’d add that the appalling desecration of burial grounds held sacred to Aboriginal people was inexcusably thoughtless and ignorant, no matter how you look at it.

In the shadow of Mt Warrinilla.

Burial cylinders, made of elaborate bark constructions, were taken from the area decades ago. It is thought that large amounts of material accompanied the burials, including bone awls, dilly bags, skin bags, ceremonial stones and clapsticks. Walsh believed this to be:

one of the greatest single sources of material data in pre-contact Aboriginal lifestyles yet discovered in central Queensland.

Controversy over the removal of a burial cylinder from the area in 1982 gathered media interest, attracting greater public support for the official protection of archaeological sites.

Roosting Nankeen Night Herons, Lake Nuga Nuga.

In the 1970s drought it was reported that numerous stone tools lay in an area not far from the shoreline of the lake, still not covered by the deposits of sediment. Clay and stone ground ovens were also visible on the lake bed.

Photo by Bernice Sigley.

And of the suddenly emptying lake? Karingbal people believe this was caused by one of the Rainbow Serpents moving from the lake and returning.

Despite what is written about the “lost tribes of the Carnarvons” the Karingbal people have survived, and continue to rightly assert their relationship with this area, including Lake Nuga Nuga and its surrounds.

A small national park, but without the lake

The Arcadia Valley, like much of the central Queensland area, was once covered in a scrub dominated by the acacia known as brigalow (Acacia harpophylla). Clearing of this area for agriculture accelerated after the Second World War with the introduction of heavy machinery.

Jim Gasteen was involved in extensive surveys of the area in the 1970s as conservationists and scientists sought to have examples of the State’s biogeographic regions included within national park reserves. He describes (in 1982) what happened in the area with the commencement of the Fitzroy Basin Brigalow Land Development Scheme in 1962:

The plan by the Government was to allocate and clear 4.5 million hectares of brigalow-dominated country north from the Warrego Highway for closer settlement. As a result of this, and other extensive private clearing during the Scheme and since, most of the lowland brigalow scrubs had disappeared by the early 1970s, leaving vast areas of over-cleared agricultural lowland to the north, south and east of the central highlands. In addition, the more accessible mixed eucalypt ridges associated with the north/south coastal ranges have now been cleared for farming and grazing. Virtually the only areas which have escaped the onslaught of an expanding agricultural industry have been the more elevated ranges where the soils are shallow and rocky and which are too steep and difficult to clear.

A patch of original brigalow scrub preserved within Lonesome National Park, at the southern end of the Arcadia Valley. Expedition National Park can be seen in the background.

Gasteen’s survey work was a critical part of the successful acquisition of some central highlands areas in national parks or other reserves, including Expedition National Park and Nuga Nuga National Park. His The Queensland Central Highlands Sandstone Region Survey Report was vital support in the effort to protect some remaining habitat within reserves. After completing a large survey of Queensland’s wetlands in the 1970s, Gasteen named 11 specific wetland areas that he felt should be accorded national park status. Lake Nuga Nuga was one of these.

Hemmed in by the retreating scarps of the Expedition, Carnarvon and Kongabula ranges, which form a beautiful backdrop to the sea of pink waterlilies blanketing the lake surface, the Lake Nuga Nuga area contains important remnants of local native vegetation in the heart of the over-cleared Brigalow lands. This important wetland region supports a large and diverse wildlife population of immense significance to Queensland’s central highlands.

While the area adjacent to Lake Nuga Nuga was gazetted as a fauna reserve in 1969, it was not until 1991 that Nuga Nuga National Park was declared over a 2,550 ha area of bush. Extensions in 1993 allowed for the inclusion of a former Recreation Reserve, increasing the park’s size to 2,860 ha (about 28.6 sq km).

The lake itself is not part of the national park, but considered vacant crown land, a waterway which falls under the jurisdiction of the Department of Natural Resources and Water. Attempts in the past to have the lake included within the national park failed after protests by some local land-owners.

Lake Nuga Nuga is listed in the National Directory of Important Australian Wetlands. It is one of 13 nationally-significant wetlands that fall within the Southern Brigalow Belt biogeographic region.

Intermediate Egret with captured Bony Bream, Lake Nuga Nuga.

Lying within the Brigalow Belt Biogeographic region, Nuga Nuga National Park protects some remnants of plant communities that were once more widespread when the Arcadia Valley area was covered in scrub.

The vulnerable Ooline (Cadellia pentastylis) is found here. This tree was once widespread from central and southern Queensland to north-west New South Wales. Ooline is a relic species from earlier and wetter geological time, and is now restricted to a few isolated areas, having disappeared from most of its previous range. The remnants in Nuga Nuga National Park are found in one of the best remaining examples of this habitat in Queensland.

Ooline, an unusual and uncommon tree, is a relic species from an earlier, wetter time.

As well as Brigalow itself (Acacia harpophylla), other notable plants species include Broad-leaved Bottle-tree (Brachychiton australis) and eucalypts such as Poplar Box (Eucalyptus populnea), and ironbark. Rosewood Acacia (A. rhodoxylon) dominates the summit and sides of Mount Warrinilla, with ironbark fringing the edges and scarps.

There are areas within the park composed of a combination of open or shrubby woodland communities dominated by Narrow-leaved Ironbark (Eucalyptus crebra) and Spotted Gum (Corymbia citriodora). Coolibah (Eucalyptus coolabah) woodland is also present.

Nuga Nuga National Park runs to the northern edge of the lake.

Remnants of Bonewood (Macropteranthes leichhardtii) scrub, a dry form of rainforest (or semi-evergreen vine thicket), are found throughout the park, while Currentbush (Carissa ovata) is a significant coloniser of vine thicket margins.

Pelicans and cormorants over Lake Nuga Nuga.

The lake itself provides valuable habitat for water birds in an otherwise arid sandstone landscape.

At dawn and dusk the trumpeting of large gatherings of swans resounds hauntingly through the stillness of the lake’s ‘dying forest’. Walsh (1988).

Tree Martins roost within the hollows of the many dead trees standing on the lake.

Many species visiting the lake are migratory and are listed under international treaties. Large numbers of birds such as Pelicans, Black Swans, Magpie Geese, Brolgas, Grey Teal, Great Crested Grebes, Pink-eared Ducks, Hardheads and Plumed Whistling-ducks use the lake at times.

Raptors such as Whistling Kites and White-bellied Sea eagles can be seen here. Whistling Kites have been adding to some nests in the lake’s dead trees for over 20 years (Walsh, 1999), and can be seen snatching Bony Bream from the water on warm mornings.

A Whistling Kite watches for Bony Bream, Lake Nuga Nuga.

The future?

Organised trips to Lake Nuga Nuga began in the early 1900s. In March 1931 The Royal Geographical Society of Australia’s Roma Branch organised the first major expedition to the lake. Led by Roma solicitor (and later Mayor) Fred Timbury, the party camped overnight before continuing on to Rewan Station and Carnarvon Gorge.

Timbury was an advocate of schemes (known as the Bradfield and Idriess) to redirect the flow of rivers inland and north for irrigation. His book Battle for the Inland, published in 1944, pushed these schemes. Following trips to Lake Nuga Nuga and Carnarvon, Timbury gave a series of lectures at Roma, Injune and Mitchell on the beauty of the Carnarvon Ranges, featuring a series of ‘Magic Lantern’ glass slides prepared from expedition photographs by Roma photographer Otto Watson.

Fred Timbury at Lake Nuga Nuga, 1930s. Photograph by Ernie Ward, courtesy Peter Keegan. About the photographer (from Walsh, 1998): The inner Carnarvon Gorge was also well known to Tom and Ernie Ward, two local identities who had lived a hermit-like existence there during the latter part of the First World War, to avoid conflict with their German fatherland … the Wards had already photographically recorded Carnarvon … Ward’s Canyon was the closed, secluded side gorge used by the Wards as a supplies and equipment store, doubling as a darkroom in starlit nights to permit processing of photographic negatives in its flowing waters.

Since then, Lake Nuga Nuga has been an increasingly popular destination for campers, fisher-folk and photographers.

Lake Nuga Nuga has been, and probably will be for many years, a place where photographers can wrestle with capturing the light. Photograph by Bill Goebel, 1950s.

Lake Nuga Nuga in the light of a full moon. Photograph by Bill Goebel, 1950s.

The sun still sets over the lake half a century on. Boiling the billy, Lake Nuga Nuga. Photo by Bernice Sigley, 2003.

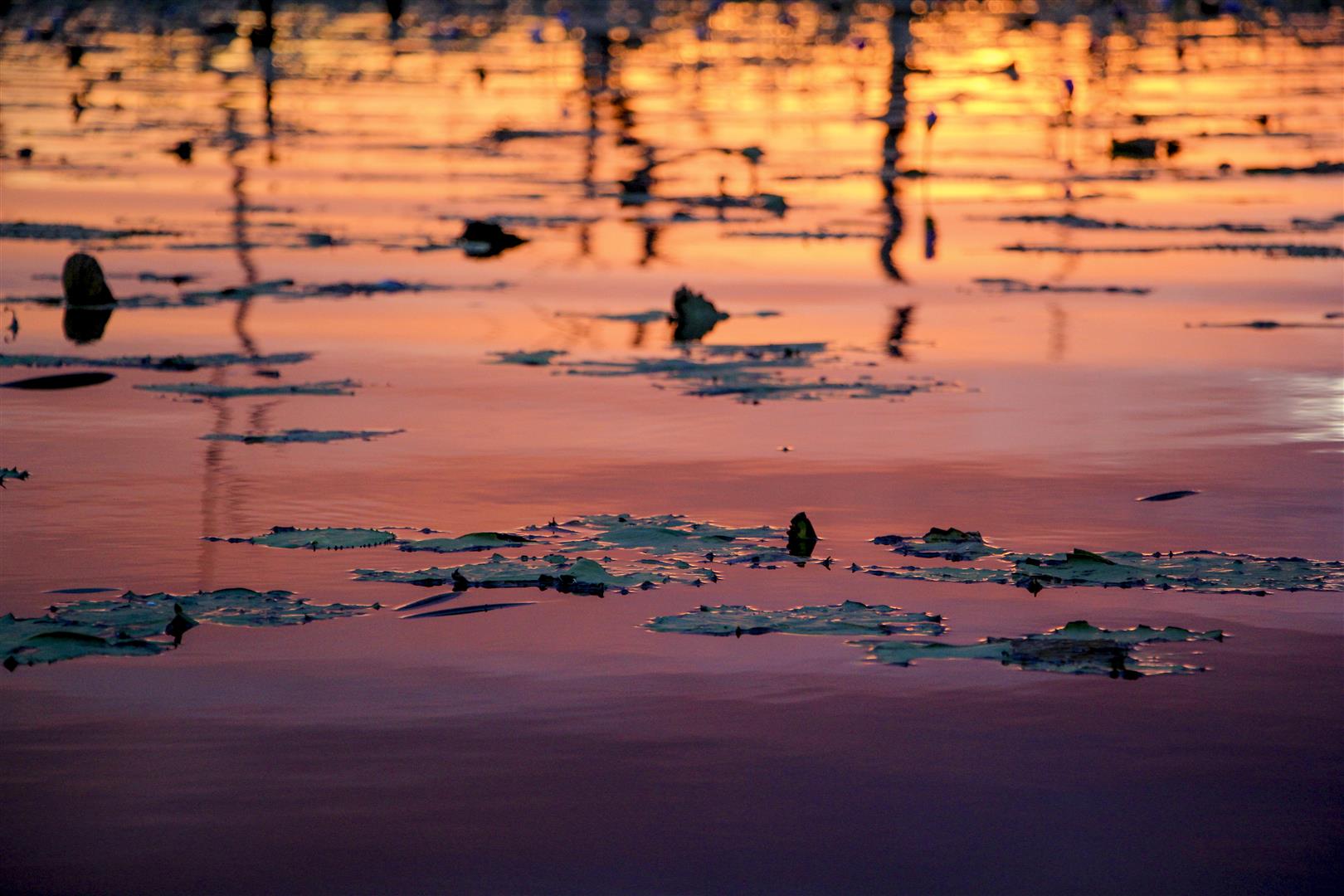

In 1986 photographer Steve Parish led the Wildlife Photo Experience Tour to the lake, and participants waded out to get a close look at the lake and its stunning native water-lillies. The lillies are there still, and make an excellent photographic subject.

Much of Lake Nuga Nuga is at times covered with the enormous purple, pink and white flowers of the native Giant Water Lilly (Nymphaea gigantea). Photos by Robert Ashdown.

Following in the footseps of some interesting photographers — the blogger doing what he enjoys most, messing about with cameras at Lake Nuga Nuga. About 2003, with his trusty old Nikon F4 and 300mm mf lens. Photo courtesy Bernice Sigley.

Val Palmer (1986) describes the joy of photographing the lake in the changing light of sunset:

With changing nuances of light, each image captured seemed to surpass the last. Such elation as the sun dipped lower, towards the bones of trees standing starkly from the lake! Then the ultimate simplicity as it set, a dull red orb, seeming to impale itself on the teeth of dead trees.

[Four sunset photos (above) courtesy Linda Thompson.]

Land currently farmed within the Arcadia Valley is regarded as the highest quality for agriculture, with a reputation as good fattening country for cattle. Pasture growth is good on soils derived from the original Brigalow, Belah, Ooline and Wilga softwood and vine scrub soils.

Another claim for use of the area’s land has accelerated, with mining exploration intensifying over the entire sandstone country of central Queensland, including the Arcadia Valley. Future threats to Lake Nuga Nuga may include water extraction and the introduction of new weed species.

The lake has seen a recent increase in people taking to its waters in powered boats. Nonetheless, it is still a serene location for most of the time. It remains to be seen what pressures will affect the lake and its small adjacent national park in the coming decades, and how it can be best protected for generations to appreciate.

I’d like to think that the Moondagarri stay sleeping beneath the mountains that overlook this magical place.

Lake Nuga Nuga sunset. Photograph by Linda Thompson.

Thanks to Linda Thompson and Bernice Sigley for permission to use their images. Thanks also to Linda for the loan of the kayak, and to Bill Goebel and Peter Keegan.

I would like to express my respect for the Karingbal and Brown River Peoples and acknowledge their past, present and emerging Elders. I respect and recognise their ongoing connection with this land.

References:

- Finlayson, B. and Kenyon, C. (2007). Lake Nuga Nuga: a Levee-dammed Lake in Central Queensland, Australia. Geographical Research. 45(3):246-261. Online here.

- Gasteen, J. (1984). Pelicans to the Rescue. Wildlife Australia, Autumn 1984.

- Gasteen, J. (1998). Back to the Bush.

- Gasteen, J. (1991). How can we Protect Queensland’s Diminishing Wetlands? Wildlife Australia, Spring 1991.

- Walsh, G. L. (1985). Lake Nuga Nuga — A Need for Greater Protection. A Brief on the Historic Significance of the Lakes Area. Queensland National Parks and Wildlife Service (unpublished).

- Walsh, G. L. (1998). Carnarvon and Beyond. Takarakka Nowan Kas Publications.

- Palmer, V. (1986). Nuga Nuga Dreaming. Wildlife Australia, Spring 1986.

Links: