It’s October 2022, and Australia has entered its third La Niña event in a row. Part of a natural climate cycle over the tropical Pacific Ocean, varying sea surface temperatures shift weather patterns, bringing floods to some regions and droughts to other places. For most of Australia, La Niña raises the chance of rain, with increased potential for more extreme rainfall in eastern Australia. In other words, it’s wet.

This is good news for some and not so for others, depending on where you live and what species you are. For things like frogs and fungi, these are good times. As a fan of fungi, it’s been a great time to see all sorts of fascinating fungi appearing around us in backyards, parks and wilder places.

This blog post presents an article by Rod Hobson on a particularly strange-looking species of fungus with a fascinating history, as well as a gallery of images of some of the fungi I have had the pleasure of photographing recently, mostly within a short walk of my front door.

“Flowers and bees often have a relationship that promotes the distribution of pollen. Some fungi have a relationship with insects that benefits the distribution of spores. It really is the strangest thing, but it is a clever strategy in Australia where flying insects are abundant. A malodorous smell often accompanies these unworldly-looking fungi (the stinkhorn – Phallales – group), but rest assured, they come in peace and are more like mother nature than the dark emerging underworld.” 2023 calendar of the Queensland Mycological Society

Behold! The Alien Space Fungus.

Rod Hobson

Winter in Toowoomba in the middle of August and I’m sitting over a computer in shirtsleeves! When I was growing up here August was miserable. The westerlies used to howl in off the Downs like a Mongol horde for days and stay. And stay and stay. “When blood is nipped and ways be foul …”, as Shakespeare so descriptively writes of winter in Love’s Labour’s Lost.

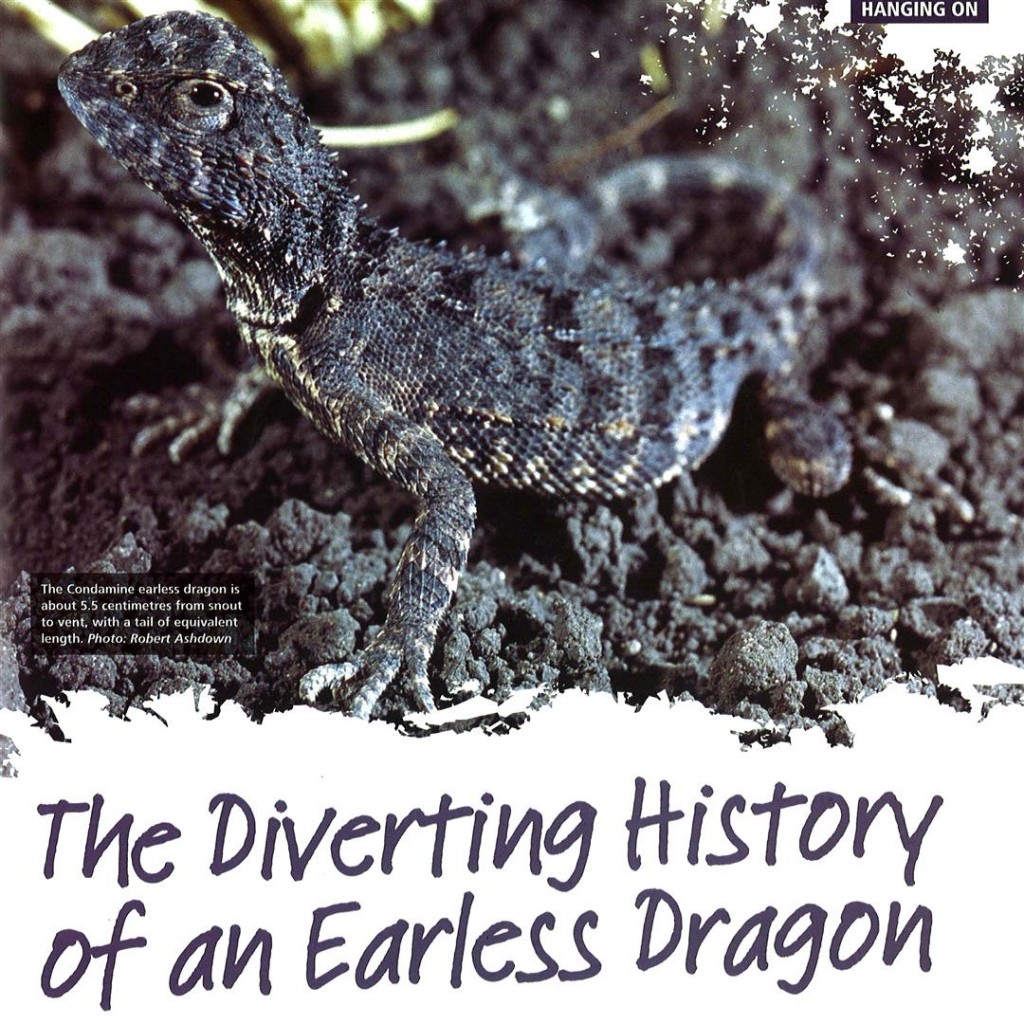

But the seasons are surely changing. Already Australian Magpies are nesting. Within the first fortnight of this month Martin Ambrose had recorded his first Painted Honeyeater of the season at his home in Dalby; a very early arrival of this lovely little spring migrant. Around this time, I also watched a foraging Spotted Black Snake Pseudechis guttatus for about ten minutes on Steele Rudd Road at East Greenmount, a magnificent reptile in glorious jet. It was out and about early in the unseasonably warm weather obviously hungry and intent on a meal. At one stage the snake passed within a hand’s breadth of my feet quite unconcerned about my presence. It was a lovely encounter. About a week before I found a pair of adult Condamine Earless Dragons Tympanocryptis condaminensis taking the sun at Evanslea, which is about a month before they usually raise their sleepy heads. There was a Shingleback Tiliqua rugosa out and about at Doctor Creek, Jondaryan, near the start of August.

For many of my friends who are of a like mind where things scaly, feathered or furred are concerned, winter however, is normally looked upon as a time of privation. The microbats and other small mammals are tucked up in torpor, the reptiles and frogs are hunkered down under stones and logs or at the bottom of the cracks in the black clays of the Darling Downs. The coastal mudflats and banks of our local wetlands are deserted. The shorebirds have taken wing for the tundras and shingle banks of the northern hemisphere to preen and strut their breeding colours. The snipe has quit our swamps, but they’ll be back soon; one of our earliest returning wading birds. The Dollarbirds, Channel-billed Cuckoos and Eastern Koels are off to warmer climes. The birdwatchers pass these dismal months contenting themselves with our scant winter visitors like the robins or the rare appearance of a Regent Honeyeater or Swift Parrot. A winter calling Powerful Owl causes all sorts of excitement. The social media hums into life. But the mammal and reptile enthusiasts are out in the cold, literally. I can appreciate their concerns but can’t really sympathise. It’s evolution. Specialists perish whilst generalists thrive. I’m interested in all sorts of stuff, ergo a generalist so can keep happily occupied throughout these drear months.

I quite look forward to winter especially if we have some good rain and mild weather, as has occurred this year. Who needs Animalia? These conditions animate many of our local plants into leaf and flower. And fungi thrive. Every winter I pass many an idyll in our bushland parks looking at terrestrial orchids and fungi. Duggan Bushland, Redwood Park and Glen Lomond are favourite hunting grounds. Two common terrestrial orchids have been out in numbers this winter in all these places. They are the Nodding Greenhood Pterostylis nutans and the Blunt Greenhood P. curta. In Glen Lomond Park recently I found over 130 Blunt Greenhoods “tossing their heads in sprightly dance” as a brisk breeze coursed down their shadowy gully.

Queens Park and the Botanic Gardens have been a haven for fungi. The mulch placed around the bases of the trees provides a fertile medium for a plethora of fungal species especially those of the family Phallaceae (order Phallales) more commonly, but unflatteringly known as stinkhorns and cage fungi. I’ve long been engrossed by the Phallaceae.

After rain, mulch around the base of trees in Toowoomba’s Queens Park erupts with a variety of emerging fungal fruiting bodies.

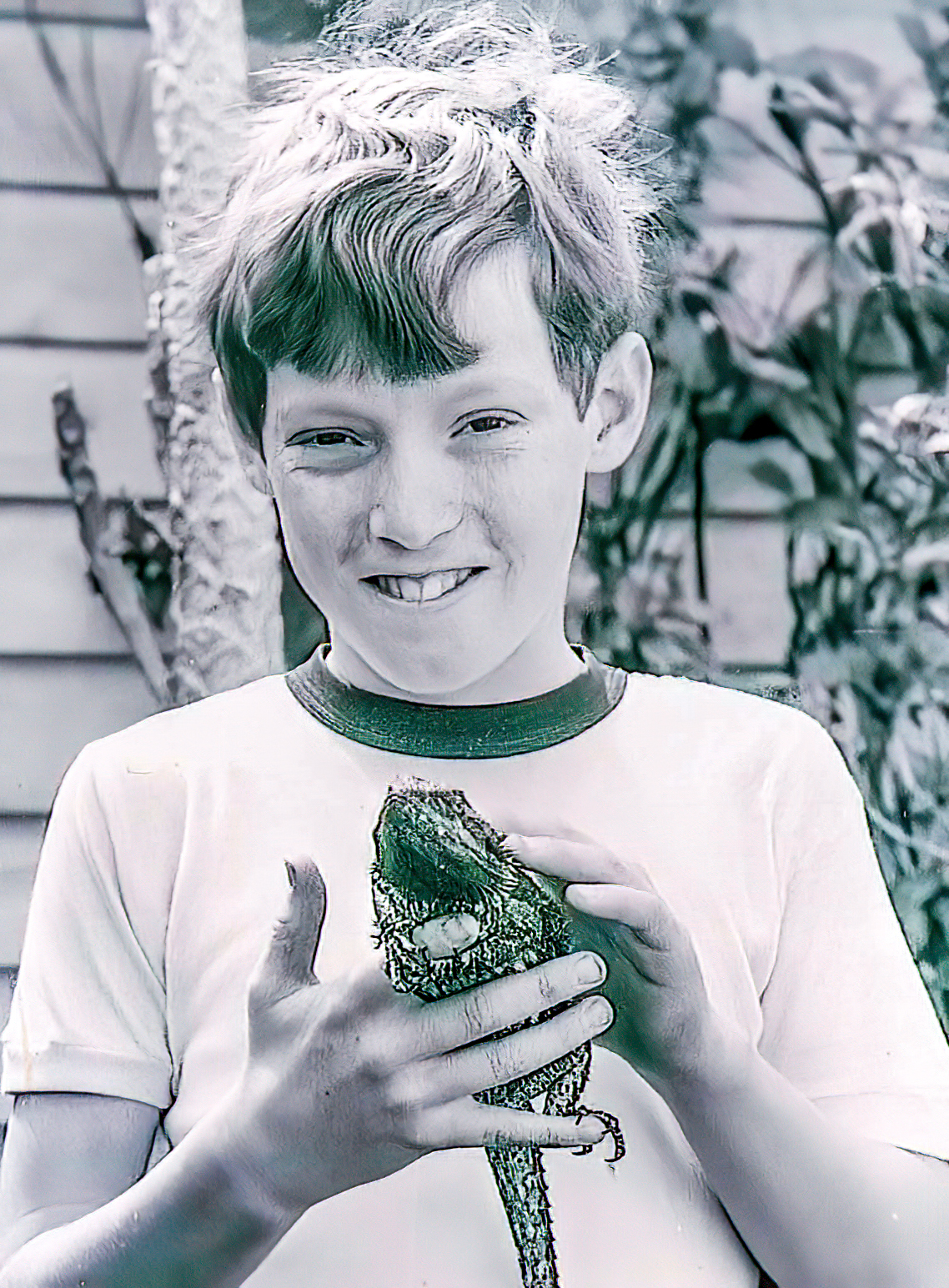

The most common of this family and one most often remarked upon is Aseroe rubra variously known as the Stinkhorn, Starfish or Anemone Fungus. In the United States, where this stinkhorn has been introduced it is also known as the Space Alien Fungus. Why should this not surprise us? Hollywood even in the dusty halls of the mycologist. Many readers will be familiar with this freakish fungus from their own back yards. I’ve known it all my life and it’s the Galah of the fungal world to me; ever so common but ever so beautiful (if you will concede that beauty is in the eye of the beholder in the stinkhorn’s case). It’s a fascinating fungus and the history and biology surrounding it is well worth pondering.

Aseroe rubra, the Stinkhorn, Starfish or Anemone Fungus. In the United States, where this stinkhorn has been introduced, it is also known as the Space Alien Fungus.

The etymology of its scientific name can be translated roughly as ‘red and juicy with a disgusting smell’. Lovely stuff. The generic name comes from the Latin ase meaning disgust plus roe translating as juice, which refers to the tarry, foul-smelling spore-bearing gleba. The specific epithet rubra means red. This refers to the red, tentacle-like ‘arms’ of the fungal fruiting body; the part poking out of the ground. The gleba rests within the curvature formed at the base of these tentacles. Aseroe rubra has the honour of being the first fungus recorded from Australia. It was discovered by the French biologist Jacques Labillardière (1755-1834) and is described in his Relation du voyage a la recerche de La Perouse published in 1800, which became a best-seller in its day. In 1804-06 Citizen Labillardière also published his magnus opus Novae Hollandiae plantum specimen now widely regarded as ‘the first general flora of Australia’ (Duyker 2004). He was also the first to publish on the flora of New Caledonia. Many of Labillardière’s botanical specimens are now held in Florence.

French biologist Jacques Labillardière (1755-1834). Labillardière’s scientific collections from the d’Entrecasteaux expedition were seized by the British when the ships reached Java. After lobbying by Joseph Banks, the collections were eventually returned to Labillardière, who arrived back in France with them in 1796. [Sketch by Julien Leopold Boilly, lithographer unknown. The original lithograph is in the Wellcome Library, London. This image was taken from http://www.anbg.gov.au/biography/biog-pics/labillardiere.jpg, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=177282]

The d’Entrecasteaux expedition was captained by Antoine Raymond Joseph de Bruni, chevalier d’Entrecasteaux. He was born in Aix-en-Provence in 1737 and was to lose his life on this enterprise. He died of scurvy in 1793 off the Hermit Islands in the Bismarck Archipelago, Papua New Guinea without finding any trace of de la Perouse.

Antoine Raymond Joseph de Bruni, chevalier d’Entrecasteaux led the expedition to search for the lost ships of Jean-François de Galaup, comte de La Pérouse (often referred to as just La Pérouse). [Illustration by Antoine Maurin – http://www.janesoceania.com/oceania_dentrecasteaux/, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=170041]

The two storm battered ships Recherche (under command of expedition leader D’Entrecasteaux) and the Esperance (commanded by Huon de Kermadec), at anchor in waters off Tasmania’s south-east coast. This waterway was later named D’Entrecasteaux Channel and the kidney-shaped bay they chose for their rest and repair became known as Recherche Bay. Image source: https://www.ourtasmania.com.au/hobart/recherche-bay

The d’Entrecasteaux expedition remained at Recherche Bay for five weeks then set sail directly for the Admiralty Islands where it had been reported natives were seen wearing French uniforms; an account later disavowed by the purported observer. No trace of the la Perouse expedition was ever uncovered by d’Entrecasteaux. The fate of the la Perouse expedition is still speculative, however there is evidence that his ships the Astrolabe and Boussole were wrecked in a storm off Vanikoro in the Solomon Islands where many of the survivors were massacred by the local inhabitants. Some were thought to have escaped this fate after constructing a small boat. They were to disappear at sea without trace. Ironically d’Entrecasteaux had earlier sailed by Vanikoro without dropping anchor. In one of those macabre footnotes that litter history on the very day d’Entrecasteaux reached Recherche Bay, Louis XV1 was taken to the Place de la Revolution (now the Place de la Concorde) to meet his fate. It is reputed that, on the eve of his death Louis asked ‘… a-t-on des Nouvelles de Monsieur de la Perouse?’ “Have you any news of Monsieur de La Perouse”. But there was none. Such is the fascinating history surrounding our fungus.

The Anemone Fungus is a native of Australia, New Zealand and South Africa. It has also been recorded on several isolated Pacific Islands including Norfolk and Lord Howe Islands. In Australia it is found from south-eastern Queensland and southwards to eastern Victoria and Tasmania. This fungus is now known from many other parts of the world, however, where its spores have arrived in the potting mix and mulch of botanical specimens. In 1829 it fruited in the Royal Botanic Gardens in Kew, southwest London and in 1992 it was collected from Oxshott Heath in the county of Surrey, southeast England (Pegler et al. 1995). It is thought to have arrived in England in potting soil via the Netherlands in 1828. Until recently (2019) all other recordings of the species in Britain have also been from locations in Surrey. Shortly after arriving at Kew, it was recorded in California, and has become well established in Hawaii and the south-eastern states of the USA. It is now the most common stinkhorn species occurring in the Hawaiian Islands (Hemmes and Desjardin 2009).

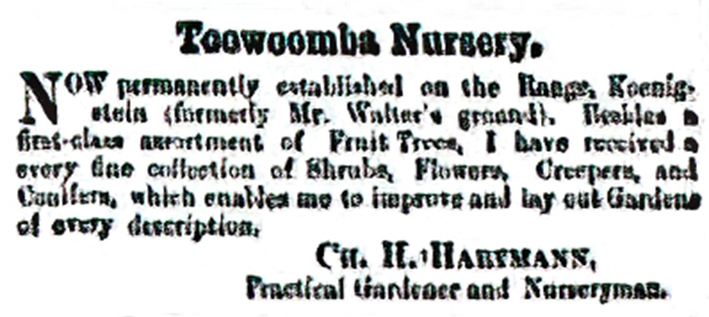

Despite the assertion that this fungus is most likely introduced to foreign locations in potting mix, it is difficult to account for its appearance in many isolated locations such as the small village of Kirinyaga in Kangaita, Central Province in Kenya. Kirinyaga is remote from any established gardens. A form with unbranched ‘arms’ Aseroe rubra var. zeylanica was described found growing in semi-evergreen to evergreen forests and high-altitude Eucalyptus stands in the Western Ghats, Kerala, India (Mohonan 2011). It should be remarked, however, that this particular fungus, and other subspecies (actinoloba, muelleriana, junghuhnii et al.) of Aseroe rubra are presently considered as synonyms of rubra by many authorities. Locally it is a very common fungus often encountered in the same situation as another common stinkhorn, the cosmopolitan Phallus rubicundus. Both these stinkhorns can be either solitary or gregarious and have certainly increased in numbers aided and abetted by gardeners’ use of mulch and wood chip that provide ideal growing mediums for them. Earlier this year I found 17 Aseroe rubra in all stages of development in wood chip under a tree in Queens Park near its boundary with Lindsay Street, East Toowoomba.

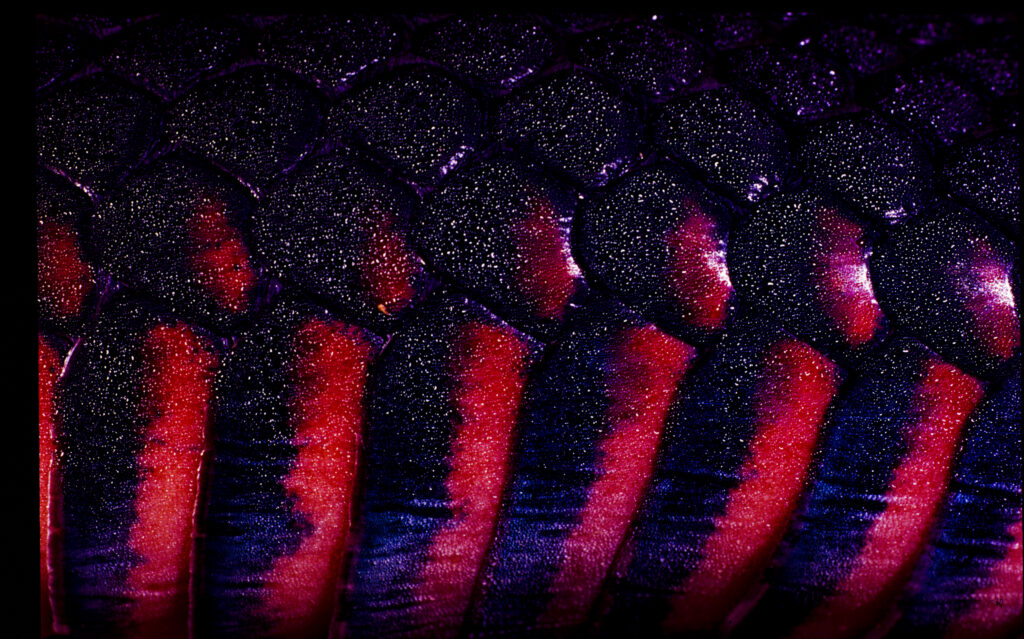

The first appearance of fungi generally lumped under the term stinkhorn and cage fungi is of a globose to ovoid immature body comprising a smooth peridium (outer casing) enclosing the gleba (spore bearing tissue) and the unexpanded receptacle, which will become the visible part of the mature fruiting body subtended or not by a column (pseudostipe) depending on species. This immature fruitbody is referred to as the ‘myco-egg’, an other-worldly looking gobbet, which I like to call the ‘Dr. Who stage’. The mature fruiting body of A. rubra is supported by a white to fleshy pink pseudostipe which grows to about eight centimetres high and three centimetres wide (Gates and Ratkowsky 2014). Atop the pseudostipe an array of gaudy red to reddish orange tentacles emerges enfolding at their base the foetid, sticky brownish spore mass of the gleba. The tentacles can reach a span of about 10 centimetres in diameter and can be single or bifurcated (divided) at their tips. The rhizomorphs or root-like structures found in fungi such as A. rubra and other Phallales attach themselves to buried wood hence their penchant for well-mulched garden beds.

These fleshy red tentacles will soon sit atop the extended tubular pseudostipe, which grows to about eight centimetres high and three centimetres wide.

The Stinkhorn (Aseroe rubra) showing black, sticky spore mass and bifurcated ‘tentacles’. Queens Park, Toowoomba.

Atop the pseudostipe of the fully emerged fruiting body of the Anemone Fungus sits an array of gaudy red/orange tentacles, at the base of which is found the foetid, sticky brownish spore mass known as a gleba.

The Anemone Fungus is only weakly odoriferous compared to other members of the family. The unpleasant smell emanating from these fungi has often been described as resembling that of rotting meat. The purpose of the smell and the gummy consistency of stinkhorns’ spore masses is to attract flies and other invertebrates that will take up the fungus’ sticky spores thereby dispersing them to new areas. A small troop of Anemone Fungus growing in our home garden was regularly visited by the metallic green Australian Sheep Blowfly Lucilia cuprina.

The rotting meat smell emerging from the fungal spore mass attracts flies and other invertebrates that will take up the fungus’ sticky spores and disperse them to places afar.

A happy fly romps about the fungus, unwittingly picking up spores that it will carry off to new places.

This strategy of attracting flies and other invertebrates to the smell of rotting flesh or dung for the purpose of fertilisation or spore dispersal is a highly successful one. Aside to the fungi it has been adopted by several types of plants including the largest flowering genus in the world, the Rafflesia of Southeast Asia. Rafflesia arnoldi from the rainforests of Indonesia has the world’s largest flower although it is often claimed that the Titan Arum Amorphophallus titanum that is endemic to Sumatra, holds this honour. The Titan Arum, though, produces an inflorescence rather than a single bloom, a fine distinction in terminology within the botanical world. Semantics aside both these plants employ insects to fertilise their blooms. Rafflesia and Amorphophallus are both called corpse flowers and these giants of the plant kingdom employ similar tactics to our humble stinkhorns to ensure their continued survival. It should be stressed, however that the distinction between fungi and the flowering plants is that the fungi utilise these animals to disperse their spores whereas the plants need them to complete the fertilisation process. Fungi reproduce asexually by fragmentation (of hyphae), budding, or by producing asexual spores with the last being the most common strategy.

Corpse Flower Rafflesia keithii, Poring Hot Spring Reserve, Sabah. The Rafflesia produce the world’s largest blooms. They utilise flies and other invertebrates in their fertilisation process. Image courtesy Terry Reis.

In our home garden we have two African succulents. These belong to the Stapelia; a genus of succulents famed for their gorgeous, star-shaped flowers – and their putrid perfumes. Ours are Black Bells Stapelia leendertziae and Zulu Giant S. gigantea and, on a warm, still day, their odour is quite distinguishable to the noses of passers-by, human or canine. Members of this genus are often referred to collectively as carrion flowers. The Eastern Skunk Cabbage Symplocarpus foetidus from North America also employs this tactic to aid in its reproduction and wasps, flies, butterflies, and stoneflies have all been recorded attending its pongy blooms. Both its common name and specific epithet leave little doubt as to this plant’s ‘attributes’. There is a multitude of other plant and fungi species that could be cited in regard to these fascinating associations, but this should suffice the weary reader and, hopefully, give cause for a moment’s solicitude when you next encounter a Space Alien Fungus invasion of your veggie patch. “Woodman, spare that tree …”. Or fungus.

References:

- Duyker E. (2004). Citizen Labillardiere, Melbourne University Publishing, Charlton.

- Gates G. and D. Ratkowsky (2014). A Field Guide to Tasmanian Fungi, Tasmanian Field Naturalists Club.

- Hemmes, D.E. and D.E. Desjardin (2009). ‘Stinkhorns of the Hawaiian Islands’ in Fungi Vol. 2:3

- Mohonan C. (2011). Macrofungi of Kerala. Kerala, India: Kerala Forest Research Institute.

- Pegler D.N., Laessoe T. and B.M. Spooner (1995). British Puffballs, Earthstars and Stinkhorns, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew.

Footnote: Anyone wishing to follow up on the early French expeditions to the Antipodes especially in regard to their natural history contributions (which easily rival those of our more lauded Banks, Solander et al.) must read Michael Lee’s beautifully written and researched Navigators and Naturalists – French Exploration of New Zealand and the South Seas (1769-1824) published in 2018 by David Bateman Limited, Auckland. A great read and highly recommended.

[This article was first published in the October 2021 edition (767) of the The Darling Downs Naturalist, newsletter of the Toowoomba Field Naturalists Club.]

Rod Hobson is a naturalist and retired Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service ranger who lives in Toowoomba, Queensland. Rod was awarded the 2021 Queensland Natural History Award by the Queensland Naturalists’ Club, an award that is presented annually to recognise people who have made outstanding contributions to natural history in Queensland.

[All photographs by Robert Ashdown, unless otherwise credited.]

A gallery of stinkhorn and cage fungi species, members of the family Phallaceae.